MUSIC is a ubiquitous and intrinsic element of individuals' lives (DeNora, 2000). Research on functions of music in everyday life suggests that making music and listening to music are the means in which individuals engage with music on individual and social levels (DeNora, 2000; 2010). The motivations for using music are varied and serve a diverse number of functions (Lamont et al., 2016), such as promoting the fulfillment of emotional, cognitive, and social needs (Hargreaves et al., 2005). Music helps to shape representations of individuals, cultural values, and emotional experiences and activities by functioning as a tool for mood regulation and arousal. In the Strong Experiences with Music (SEM) project, Gabrielsson (2010) suggests that most of the SEM experienced by individuals occur in the presence of others, and that individuals deliberately choose to listen to music to evoke memories of these experiences, which serve as a self-reassuring emotional tool. Furthermore, how individuals respond to music depends on the influence of three elements: the listener/performer, the music itself, and the context (Hargreaves, 2012). This is described as the "reciprocal feedback" model, since any of the three elements can affect the other two simultaneously, which causes a bi-directional influence (Hargreaves et al., 2005). This model shows how the interaction between the three elements is the basis for individuals' responses to the music.

Music responses are dependent on the arousal factors, emotional responses, and influence of social psychological elements, and are the basis for individuals to develop musical preference and liking (North & Hargreaves, 2008). Previous research on the social functions of music suggests that musical behaviors bring people together by shaping cultural values and developing self-identity (Tarrant et al., 2001). Moreover, sociologists have demonstrated the importance of emotional responses for developing social structure or building social groups (Adorno, 1976; Weber, 1958; Willis, 1978). Music serves as a "soundtrack" (DeNora, 1997, p. 56) for constructing intimate occasions between two individuals, and it might even suggest the quality of that relationship (DeNora, 1997).

Previous research offers different perspectives on the uses of music with infants. This research has been mainly focused on the use of infant songs – songs specially made for infants, e.g. lullabies or nursery rhymes (Longhi, 2009; Trainor, 1996; Trehub & Trainor, 1998; Tsang & Conrad, 2010) – independent of parental involvement, meaning that it ignores the potential effect that mothers' self-selected music might have on the mothers' and infants' behavioral and emotional responses. The benefits of self-selected music have been studied under different research scopes, such as health and well-being (Batt-Rawden, 2010), self-identity (Tarrant et al., 2002), and experimental aesthetics (Hargreaves & North, 2010), but they have not been addressed in mothers' everyday life in early motherhood.

Previous research on the uses of music in everyday life is extensive, describing music as an active element for establishing personal and social life (Batt-Rawden & DeNora, 2005; DeNora, 2000; North et al., 2004; Sloboda et al., 2001; Sloboda, 2010). Nonetheless, previous research has not addressed that mothers experience specific lifestyle changes in the early stages of motherhood and how the uses of music might impact mothers' everyday lives. The possible contexts in which they might engage with music are as varied and diverse as any individual's context. The naturalistic experiences of mothers are closely related to the transitional period of adjustment into motherhood (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2006). This adjustment is related to a "transitional lifestyle change" (Currie, 2009, p. 653), and previous research has highlighted how this period is considered by mothers as challenging and sometimes stressful (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2006; Lee & Gramotnev, 2007). A reason for this might be that mothers need to adapt to different roles at the same time, fulfilling social expectations in each role (Barnett & Baruch, 1985). The adjustment and mental health of a woman in motherhood has an impact on maternal behaviors, and on the safety and general development of the infant (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2006).

The extensive literature focused on infants' responses to music suggests the benefits and impact of music during infancy (Edwards, 2011; Fancourt & Perkins, 2017; Milligan et al., 2003; Trainor, 1996). Studies have assessed the impact of mothers' communication styles, such as infant-directed speech or maternal singing, and have suggested that maternal communication demonstrates the mother's sensitivity. These communication styles serve as a tool for enhancing the infant's attention, which helps to communicate positive affection (De L'Etoile, 2006, 2012; Trainor, et al., 2000). Furthermore, studies have suggested that the expressiveness of the mother's vocalizations can be associated with the emotional communication between mother and infant, and therefore with the attachment style developed (Murray et al., 1993). These findings suggest that the expressiveness of maternal vocalizations is affected by the quality of maternal attachment, and this therefore impacts on the infant's emotional response and regulation. Social behaviors are evident in mother–infant interactions (Stern, 1971) and are musical in character (Hargreaves et al., 2005). Music and dance are intrinsic elements in infant–mother non-verbal communication. Malloch and Trevarthen (2009) suggest in the theory of communicative musicality that these innate musical interactions influence the infant's current and future social communication skills, and that they also serve as a basis for self-identity and social identity (Malloch, 1999). Previous research, however, has not addressed how the uses of music might impact social behaviors and non-verbal communication cues during mother–infant interactions.

The observation and study of mother–infant interactions has been researched from different perspectives. The pioneer attachment theory by John Bowlby (1969) suggests that it is during mother–infant interactions that maternal attachment is developed. It is the consistent proximity and care over time the basis for securing the attachment between mother and infant. And consequently, promote an emotional tie characterized by a powerful emotional relationship. Furthermore, The Strange Situation Test (TSST) by Mary Ainsworth (1978) is the second referential attachment theory, which considered new elements for research, such as parenting styles and behavioral patterns. TSST introduced the idea that attachment can be categorized by behaviors, such as secure, avoidant, ambivalent, and disorganized behaviors. Moreover, it has been suggested that it is maternal sensitivity, the central feature in mother–infant interactions, that fosters the development of a secure pattern of attachment. Mothers need a consistent and accurate interpretation, along with appropriate and contingent responses to their infant's signals, in order to nurture the development of security. Further studies based on TSST have concluded that it is through behavioral patterns and their synchrony during mother–infant interactions that the attachment style can be explored and observed (Isabella & Belsky, 1991). Gaze and facing position are considered central attachment behaviors during mother–infant interactions, creating contingent behavioral patterns between mother and infant (Stern, 1971). However, the synchrony of these behaviors serves as a behavioral descriptor that might reflect the quality of mother and infant interaction (Cohn et al., 1990; Isabella & Belsky, 1991). Early experiences of maternal attachment determine the development and response of later relationships (Bowlby, 1969; Prior & Glaser, 2006). Moreover, early experiences bring emotional tools and social competence, which affect the infant's general development (Davidson, 1994; Gerhardt, 2014). Research has revealed that positive feelings experienced during the early stages of life enhance infants' immune system responses (Davidson, 1994), and that this might affect the brain structure (Gerhardt, 2014). The mother's unconscious guidance for the infant's emotional regulation occurs through non-verbal communication, such as facial response, vocalizations, touch, eye contact, and the mirroring of all these elements (De L'Etoile, 2012; Gerhardt, 2014; Smith et al., 2015; Russell & Belsky, 1991). However, there is evidence that maternal sensitivity and the mother's emotional state are important elements that are needed in order to meet the infant's needs and secure attachment (Steele et al., 1996). For example, infants of non-depressed mothers can match the level of affective expression performed by the mother through a process of bi-directional influence. On the other hand, when depressed mothers cannot meet this pattern, acting serious while their infant is positive, their infants avert their gaze and turn away (Cohn et al., 1990). A person's ability to respond effectively and affectively to others depends on their own emotional state (Boer, 2009). Motherhood is known to be an emotional challenge due to its constant responsibilities and expectations (Barnett & Baruch, 1985). Women adapting themselves to their new role as mothers tend to find it challenging to meet the needs of a newborn and accept their new identity (Choi et al., 2005). Thus, mothers tend to use strategies to maintain their sense of well-being, such as meeting with friends, building a support network, or working out (Currie, 2009).

Aims

Considering the gaps within previous literature, two studies were conducted to provide initial data and explore if mothers' uses of music during everyday life (singing and listening) might facilitate maternal bonding. The effect of self-selected music was explored, along with elements that could impact the development of maternal attachment, such as motherhood experiences, mother–infant interactions, coping strategies, parental stress, and subjective feelings of maternal bonding.

Ethical Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Sheffield Ethics Committee. All participants received and signed informed consent forms.

STUDY 1

The present study explored how mothers use music during everyday life, and the extent to which they feel it plays a role in their developing attachments with their infants. Equally important, it considered the possible influence of mothers' experiences and mother–infant interactions, which are closely related to the transitional period of adjustment into motherhood (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2006) – an adjustment which impacts maternal behaviors that are important elements for securing attachment (Steele, et al., 1996).

Method

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were recruited using a snowball sample procedure. The researcher studied a cohort of women transitioning into motherhood. Eight mothers were recruited to participate in the interview. All participants were from England, specifically from London and Sheffield. The mean age of participants was 35.3 years (SD=1.68) and their infants were under 12 months old, with a mean age of 9.62 months (SD=2.66). Other demographics were not included, since they were not considered in any part of the analysis.

DESIGN

Participants engaged in a 15-minute, semi-structured interview, which inquired about mothers' uses of music (singing and listening to music), and whether they used music as a tool for bonding with their infant. The questions during the interview guided, rather than dictated, the process of the interview, since they were adapted to the interesting issues which arose from the participants' particular contexts. The questions were based on exploring the details of how, why, what, and when mothers use music. For example, "How do you use music?" and "How often do you sing [listen to music]?". Moreover, the interviews explored if music was selected for the mothers (self-selected) or for the infants. For example. "What kind of music do you like to sing [listen to] when you are with your baby?", "And by yourself?", and "Do you sing [listen to] what you want while you are with your baby [during your interactions with your baby]?". Furthermore, the interviews explored the context in which music was used, e.g. "Do you sing [listen to music] while you are doing any other activities?" and "Do you sing [listen to] music during a specific activity with your baby?". The interviews also explored the purpose of using music, e.g. "Could you say why you listen to music [sing]?". Finally, participants were asked if they use music as a tool for bonding with their infant, e.g. "Do you think the music you sing [listen to] helps you to feel connected with your infant?". The interview duration varied from 15–30 minutes (M=26.6, SD=6.34).

ANALYSIS

The analysis of the data collected takes into account the potential complexity and vulnerability associated with mother–infant interactions and motherhood strategies (Mukherji & Albon, 2018). Therefore, the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Smith et al., 2009) approach was utilized to describe and understand participants' personal experiences and interpretations of this specific phenomenon. The IPA approach and the sample size allowed the researcher to focus on individual experiences and participants' "personal meaning and sense-making" (Smith et al., 2009, p. 45) of the uses of music, and on their motherhood experiences. The data collected was analysed using NVivo 12 software.

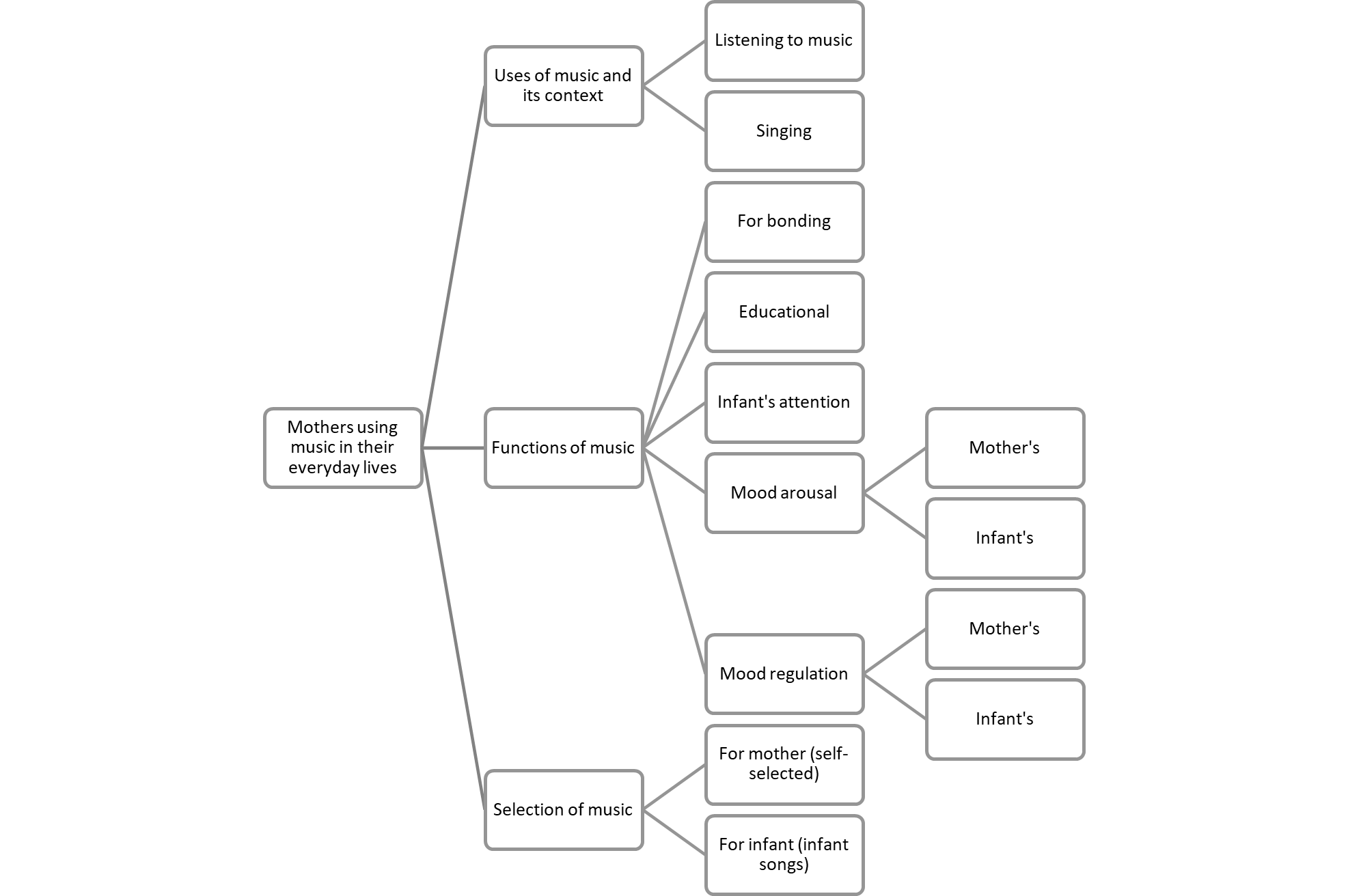

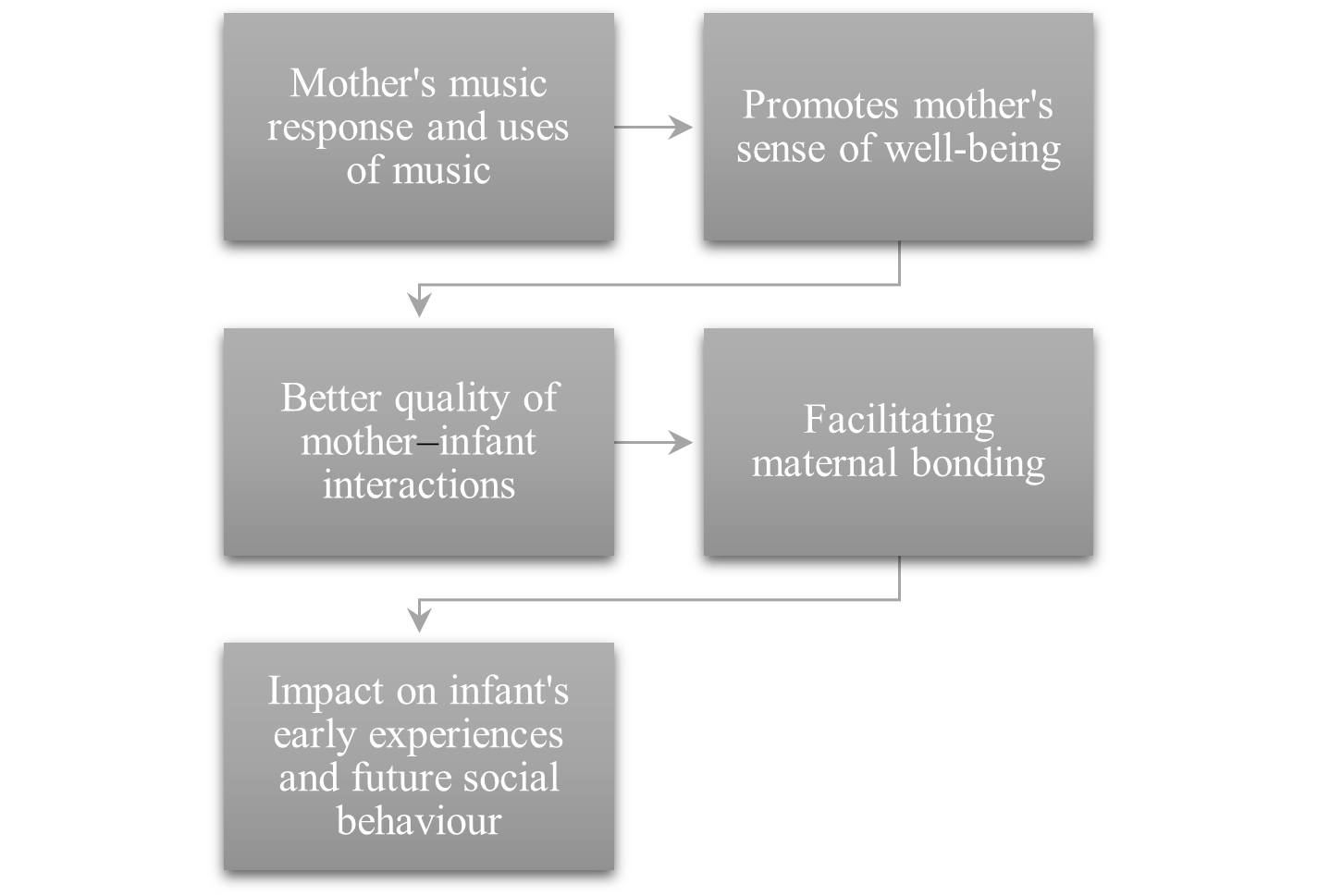

The interviews were transcribed by the researcher; the three main themes that were identified emerged from the transcripts and were not developed in advance (see Figure 1). The data retrieved was mainly based on the mothers' uses of music and how they relate to their motherhood experiences, as well as their interactions with their infants and the development of attachment.

Results and Discussion

USES OF MUSIC AND ITS CONTEXT

Listening to music and making music are the two main ways individuals might engage with music (DeNora, 2000). Maternal singing might not be considered a formal way of music making; however, due to its musical features, like well-defined rhythmic and pitch patterns (Trehub et al., 2010), it can be considered music making. Participants reported that they tend to listen to music while doing other activities, such as domestic housework or commuting, or when doing activities by themselves. As suggested by Sloboda et al. (2001) participants "linked [music] between activities/contexts and their psychological functions" (p. 13).

If I'm on my own, I use it while I do yoga, working out, or stuff like that. And sometimes we just like to put some nice sounds on [in] the background, it helps to make the house happier and my baby happier. (P3, Interview)

I put music [on] while cleaning, while I'm doing some work at home. (P5, Interview)

Furthermore, participants listened to music every day while interacting with their infants, since they considered it an effective tool for fulfilling their infant's different needs (see "Functions of Music" section).

Yes, we listen to music almost all day and mostly when she is awake, but all the time we have music as background. […] it has been very helpful for me to put some classical music [on], and it helps me a lot [with] relaxing my baby. (P3, Interview)

Charles (pseudonym) needs music to dance, so we are always listening [to] something. (P6, Interview)

Participants, however, stated that they only sing when they are with their infants, since it is the only time they feel confident singing. All of the participants reported singing to their babies during activities like breastfeeding, bedtime, or bath time.

Well, I don't like singing that much, but I mainly sing to my baby at night. […] But if it's singing, maybe there is more connection, because I usually only sing to him. (P1, Interview)

No, just singing. I sing to him every day while he is having his meal. We can sing along for an hour! (P6, Interview)

FUNCTIONS OF MUSIC

Participants tended to use music to fulfill either their infants' or their own cognitive, emotional, and social needs (for bonding with their infants).

COGNITIVE

Five participants agreed on using music for educational purposes, specifically to introduce a second language, new words, or new concepts to their infants.

I'm also used to [singing] to him songs with the ones he can do something with them. Like, for example, some rhythms or songs that have the sounds of the animals, so we can imitate the sounds of the animals and learn how they sound. […] I see music more like an education resource, like helping him to teach him some words, letters, shapes, animals. (P5, Interview)

Furthermore, seven participants used music to get their infant's attention during mother–infant interactions, such as playtime, breastfeeding, or during meals. Regardless of whether they were listening or singing along to music, they agreed that it was an effective tool to get the infant to focus.

Yes, in a way. I don't know why, if there is no music while he's eating, he just doesn't eat, he is just playing around with the food. But then I put [on] some music and he starts to eat, he is more into actually eating the food. So, I really find it very helpful. (P5, Interview)

EMOTIONAL

As for the emotional domain, participants tended to use music for mood arousal and mood regulation for themselves and their infants. They commented that they tend to use certain kinds of music according to their mood and their needs. Specifically, how participants use music with their infants is closely related to positive or negative experiences and helps to fulfil their infant's and their own emotional needs.

[…] it seems that he is starting to have tantrums, so he goes to the floor and [starts] crying. So last time he had one, we [started] singing and dance the "Conga" [laughs]. Yes, it was like he thought, "Oh, I think that's more fun than just lying here crying." So, he got up and [started] dancing. I mean I was just singing [sings melody of the song] and then suddenly, he just got up, and we start dancing. So, it seemed that he forgot about his misery, or whatever he was suffering about [laughs]. It was good! […] Yes, definitely! It helped me to get my head straight again. (P6, Interview)

I think [it] is important to use it [music], because it makes her happy, and makes her dance, she loves dancing. As long as she enjoys it, for me it's fine, I'm happy. (P3, Interview)

It was discovered that mothers often sing familiar music to their infants because it helps regulate their own mood, and because they feel comfortable singing this music.

I mainly sing to my babies at night […] I mainly sing songs that I know and […] ones that I feel comfortable with, you know, with the ones I feel comfortable singing. Mostly, because that also relaxes me too. (P1, Interview)

Participants related using music to fulfill their own emotional needs to activities they tended to do by themselves. They shared, however, that these moments do not often happen and that, since becoming mothers, they don't feel free to use their own music. Nonetheless, all of the participants identified using their own music either for mood arousal or mood regulation while doing activities, such as housekeeping, working, commuting alone or working out.

I don't listen [to] so much music for my own now, since he was born actually. I used to listen to music while I was walking to work or when I was coming back home. But now, unfortunately [I] don't. (P5, Interview)

But if I'm doing something like more simple or just sorting something in my computer or at home by myself, I'm just listening to music. […] It just makes things easier. For example, I have been listening to some Etta James lately, is music that I enjoy. (P2, Interview)

SOCIAL

Participants identified using music as a way to bond with their infant. Firstly, participants described the moments when they feel more and less connected with their infants. Secondly, participants identified using music during these moments, mostly when they are feeling connected to their infants. Lastly, participants stated that they find music an effective tool for bonding with their infants.

No, I'm not always connected with my baby, there are moments in which I don't feel connected with her. […] It's very difficult for me to understand what exactly does she need […] because I'm already upset. So, I feel we are not connected or that we are not in the same mindset. (P2, Interview)

[…] moments like this, when [we] are just having fun, when we are playing and dancing to music, we are looking into each other, it's something amazing for me to see, I am always very touched! (P8, Interview)

I think music is the most important one. Because when I'm breastfeeding, I always sing to him. And [it] is the moment when I feel more connected to him. (P4, Interview)

SELECTION OF MUSIC

What purpose do infant songs and self-selected music serve to mothers? Only two of the participants stated that they never use infant songs during interactions with their infants, since they are not interested in "introducing such simple sounds and music" to the infant. The other six respondents stated they use both infant songs and self-selected music equally. From the participants' statements, three main patterns were identified: a) participants often use infant songs to get the infant's attention during playtime, during distressed episodes, or when the mother needs to do another activity; b) they tend to use self-selected music during "intimate" interactions with their infant, such as breastfeeding or bedtime; and c) they consider it important to share their self-selected music with their infants.

Thinking about it, I mostly do it when I'm trying to get her attention. […] [Infant] songs that have the sounds of the animals, we can imitate the sounds of the animals. Just to involve him and try [to get] him to participate, because he obviously is not a singer, but he's always trying to [join in]. (P4, Interview)

There's this song, "You Are My Sunshine". I'm always singing it to her. I like it very much […] and I like singing it to her at bedtime. We have this routine of cuddling before I put her to bed, and I always sing this song to her, it feels so close and intimate, it's definitely our moment! (P2, Interview)

I think, in a way, we want him to listen [to] the same music as us, of course maybe that won't [happen], but deep inside, we are hoping that. I think it will bring us closer in the future. (P4, Interview)

Conclusions

The present study provides initial data on how mothers use music in everyday life with infants less than 12 months old. The study considered motherhood experiences and mother–infant interactions, which relate to the transitional period of early motherhood. Moreover, it considered how mothers use music in everyday life, exploring the uses, motivations, purposes, and selection of music that participants use. A general overview of the findings suggested that mothers use music as part of their interactions with their infant, as well as by themselves. Participants, however, often felt more confident when singing to their infant than when singing by themselves or in other contexts. General motivations for using music included serving their infant's and their own social, cognitive, and emotional needs. Mothers found music an effective tool to enhance their infant's attention span and regulate their infant's mood. Similarly, they often use music to regulate their own mood during a distressed episode with their infant or for mood arousal while doing activities by themselves. Specifically, mothers tend to use infant songs to keep the infant focused during activities, such as playtime and feeds, or to keep the infant entertained while they do other activities. Mothers use self-selected music mainly during intimate interactions with their infants and while doing activities by themselves. Mothers prefer to sing their self-selected music to their infant, since they feel more comfortable with it, and thus feel more connected to their infant. Similarly, they use their self-selected music to regulate or arouse their own mood while doing activities by themselves, such as housekeeping, working out, or work.

Mothers in the transitional period into motherhood tend to have a mixture of experiences, including different positive and negative experiences that might impact their general well-being and their ability to bond with their infant (Milligan et al., 2003; McVeigh, 1997). The motivation for using music correlates with these experiences. For example, mothers tend to feel less connected with their infant during distressed episodes; however, they use music to cope with these episodes. Thus, mothers tend to use music for regulating the infant's mood during a stressful situation (Ghazban, 2013), which at the same time helps them to regulate their own mood. Likewise, they use music to reinforce a positive experience with their infant, which helps them to feel more connected. Furthermore, as previous research suggests, mothers need to have time for themselves to help maintain their sense of wellness, and they need to recognize the importance of striking a balance between their own needs and those of others (Crittenden, 2001; Koniak-Griffin et al., 2006). Mothers tend to do different activities by themselves intuitively as a coping strategy (Currie, 2009; Walker & Wilging, 2000), and they tend to consider it important to use self-selected music for mood regulation. Hence, the previous findings highlight the importance of music as a tool to promote mothers' general well-being.

Giving examples of strategies that can be easily adapted to the transitional period of the early stages of motherhood might serve as an effective tool for promoting mothers' general health and well-being, and therefore enhance the quality of maternal bonding. Music could offer a sustainable and easily accessible tool for this purpose. Nevertheless, further research needs to be done to expand our knowledge about the impact that uses of music might have on mothers' everyday lives and their interactions with their infants. Detailed exploration of the effects of music during mother–infant interactions might help to explain how music might affect the quality of mother–infant interactions, and how it might be used for enhancing the development of maternal bonding.

STUDY 2

The second study aimed to explore the extent to which mothers' uses of self-selected music (singing or listening) might facilitate maternal bonding by considering elements such as self-reported maternal bonding, self-reported parental stress, experiences of the transition into motherhood, and behavioral patterns during mother–infant interactions.

Method

PARTICIPANTS

The participant recruitment criteria included mothers with typically developing 0- to 12-month-old infants. The exclusionary criteria included any medical condition that might potentially impact the participant's lifestyle, how they interacted with their infant, and how they experienced their transition into motherhood (Pinelli et al., 2008), such as a diagnosed mental illness, an eating disorder, or a chronic or congenital illness. Eight dyads of biological mothers with their four- to eight-month-old infants (M=6, SD=1.77) were recruited from the Sheffield area. Participants were recruited by snowball effect through Facebook groups. All participants had a higher education degree and were married or in a civil partnership. Of the participants, 75% (n=6) were employed; of this 75%, four were working part time at the time of the trial and two were on maternity leave. Five participants were first-time mothers, while the others had between two (n=2) and three (n=1) children. Of the infants, 50% were female (n=4). Previous research suggests that maternal age might determine the perception of "good" parental practices (Wenham, 2016). The study aimed to reduce participants' potential biases around motherhood strategies. Hence, the mothers' age was not asked and was deliberately not included in any part of the analysis. All participants received a £20 Amazon voucher after completing the trial.

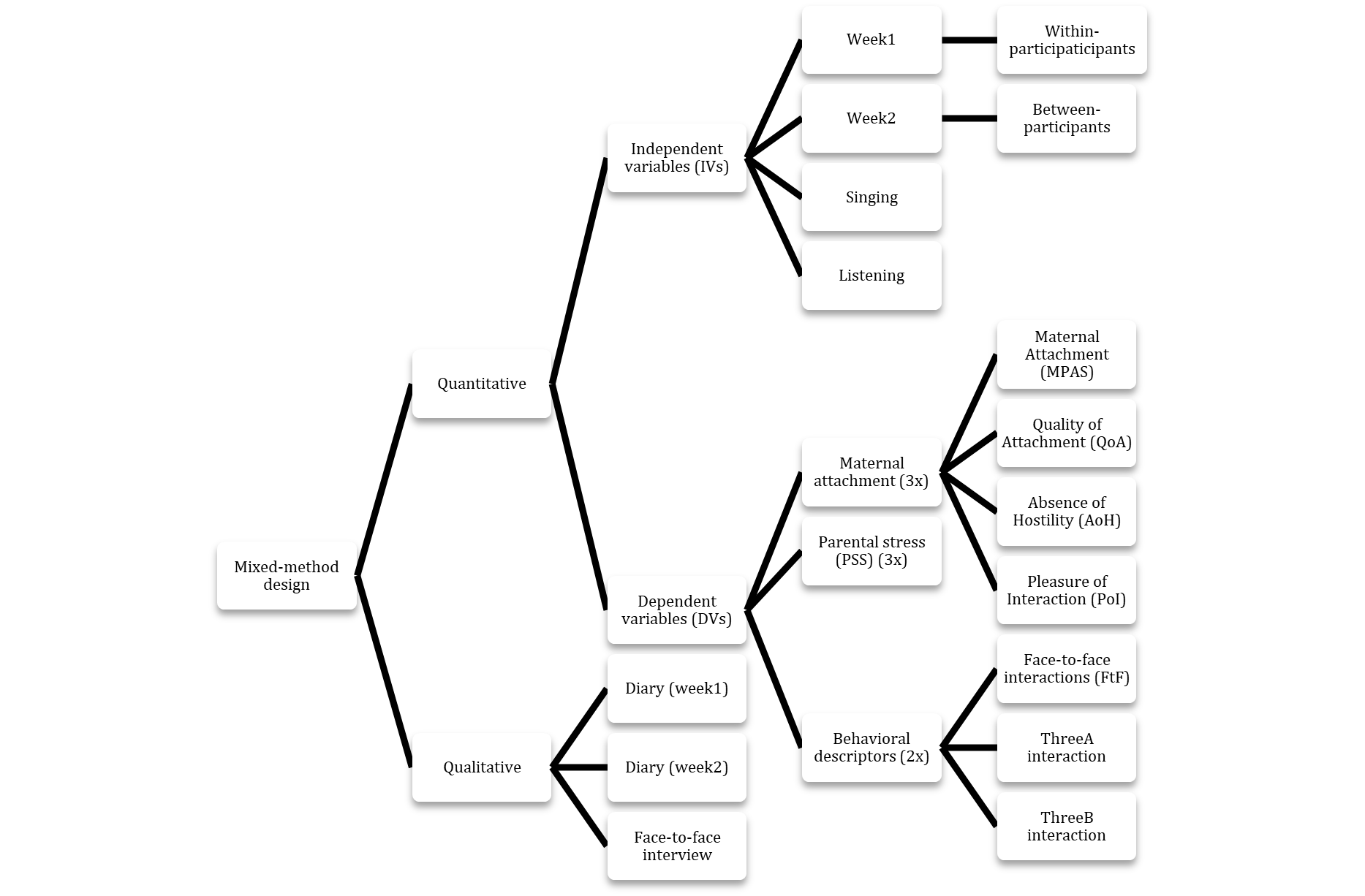

DESIGN

Due to the complex nature of researching human interactions in naturalistic settings and the exploratory basis of the study (Mukherji & Albon, 2018), the design of the study necessitated a mixed-method approach. The study consisted of a two-week trial with a mixed-subject design (within- and between-participants), with the two weeks of the trial (2x) and the uses of music in everyday life (singing and listening) (2x) as independent variables (IVs). The first week was the control week (week1). For the second week (week2), participants were put into the two condition groups (between-participants). The allocation of participants was based on their general music activities with their infant and on their confidence to sing to their infant. Consequently, the participants were not randomly assigned a group. The design of the two condition groups was based on the uses of music in everyday life: making music as a form of singing and listening to music.

The dependent variables (DVs) were maternal attachment scores (3x), parental stress scores (3x), and the score of the behavioral patterns during mother–infant interactions (2x). Moreover, the study considered the participants' self-reported experiences during the trial to be essential, and for that reason the analysis of self-reported diaries (2x) and face-to-face, semi-structured interviews was included.

MEASURES AND DATA COLLECTION

- Online background questionnaire. Two sections were included: participants' general information (this was where the background and medical information of the dyad was included) and the general activities of the dyad, including information regarding general uses of music and the participants' confidence to sing to their infants.

- Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale (MPAS) (Condon & Corkindale, 1998). The MPAS consists of a 19-item, self-reported questionnaire, which was designed to be used during the infant's first year of life. The items are divided over three subscales which encompass the confidence and assessment of the mother's subjective feelings towards their infant. The Quality of Attachment (QoA) subscale includes 9 items (e.g. "over the last two weeks I would describe my feelings for the baby as: dislike [1] – intense affection [5]"); Absence of Hostility (AoH) with 5 items (e.g. "when I am caring for the baby, I get feelings of annoyance or irritation: very frequently [1] – never [5]"); and finally the Pleasure of Interaction (PoI) subscale with 5 items (e.g. "when I am not with the baby, I find myself thinking about the baby: almost all the time [5] – not at all [1]"). The item responses are based on 2-, 4-, or 5-point scales. The minimum and maximum values are: a) 19 and 95 for the total MPAS; b) 9 and 45 for the QoA subscale; and c) 5 and 25 for the AoH and PoI subscales. The sum of the 19-item responses signifies the quality of mother–infant attachment.

- Parental Stress Scale (PSS) (Berry & Jones, 1995). This 18-item questionnaire measures parent-perceived stress and considers positive and negative aspects of parenthood, such as the experience of pleasure in the parental role (e.g. "I am happy in my role as a parent"), rewarding experiences (e.g. "my child[ren] is an important source of affection for me"), nursing demands (e.g. "caring for my child[ren] sometimes takes more time and energy than I have to give"), and lack of control (e.g. "I feel overwhelmed by the responsibility of being a parent"). The items' responses are based on a 5-point scale: strongly disagree [1] – strongly agree [5], which creates an overall score with minimum and maximum values of the scale (18–90).

- Online diaries. Participants kept two online diaries for seven consecutive days, one for each week. The general design was a semi-structured methodology, which was considered necessary to addressed sensitive topics such as, motherhood experiences or feelings regarding parenting. Hence, it was designed to build rapport with participants and reduce the sense that the study was intrusive. The first week diary (control-diary) retrieved information about participants' general activities with their infant, if there was any music involved during their interactions, descriptions of difficult situations, coping strategies, and descriptions of their emotional state. The second diary (IV-diary) included the same guidelines as the control-diary, with additional instructions on writing details of the assigned condition (i.e. singing or listening to music), considering whether the condition helped participants to cope with difficult situations and if it had an impact on their infant's behavior. The instructions indicated that mothers needed to use their own selection of music, and that they needed to write the time, place, purpose, and specific music used in the diary.

- Interaction videos. Two interaction videos of 15

minutes were recorded. These videos aimed to record

mother–infant interactions. The videos considered the

analysis of three behavioral patterns: face-to-face

interactions, and two three-step contingent exchanges: ThreeA

(mother's response, infant's response, mother vocalization) and

ThreeB (infant's vocalization, mother's response, infant's

response). The length of the videos was based on previous

research on behavioral maternal interactions (Mingo &

Easterbrooks, 2015; Isabella & Belsky, 1991; Stern, 1971).

The videos considered a naturalistic approach; the researcher

left the room after setting up the recording equipment and

giving time to allow the infant to get used to the equipment.

Participants chose the time and setting for the video

recordings. At this point, the importance of familiarity, daily

routine, noise control, and distractor effects was highlighted;

all participants chose their homes for the video recordings,

which took place while the mothers were alone and the babies

were awake. The first video, recorded after the trial's first

week, was considered the control condition (control-video), in

which mothers were asked to do any daily activity with their

infant. For the second video (IV-video), recorded after the

second week, mothers were asked to do a daily activity using the

condition assigned.

The video was recorded using a GoPro Hero 5 Black, with a 4K HD recording format. The camera angle was set by using a Manfrotto MVH500A Video Tripod, and it was set according to the mother's angle in relation to the camera and general view of the infant. The GoPro camera produced a sharp image and wide video angle, which allowed it to record the frontal view of the mother and the side view of the infant without the need for two cameras. - Follow-up interview. The follow-up interview was

designed as a 15-minute, semi-structured interview. The duration

of the interview was based on Study 1 and the participants'

availability. The role of the researcher was of vital

importance, in order to give participants confidence and create

a safe space.

The interview was recorded face-to-face using a Tascam DR-05 audio recorder. The online background questionnaire, MPAS, PSS, and online diaries were inputted into Google Forms and sent via email to participants.

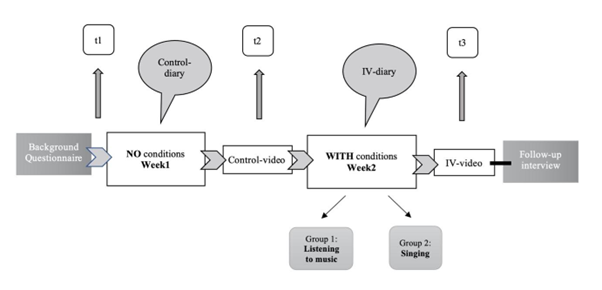

PROCEDURE

Prior to the trial, all participants received an email with a link to the background questionnaire and a copy of the ethics forms. During the trial, participants were contacted at three stages: at the beginning of the trial (t1), before starting week2 (t2), and at the end of week2 (t3). At t1, participants received instructions and forms of the MPAS, PSS, and diaries. At t2 and t3, participants received further MPAS and PSS forms. The control-video was recorded on t2, and the IV-video on t3, along with the follow-up interview.

The instructions for week2 were as follows: "On the following link you can fill in the diary for week2. The only difference this time is that you will have to listen [sing] to your own selection of music with your baby at least once per day and write down in the diary what your selection was and during which activities you listened to music [sang]. What do we mean by your own selection of music? It's the music that you prefer to listen to. Sometimes mothers select the music they listen to with their babies in mind, choosing infant songs or classical music. This week, at least once per day, listen to music you like with your baby."

As for the IV-video, the instructions were: "During this recording you can choose any activity you normally do with your baby while listening to [singing] your own selection of music. You can choose any activity that you feel comfortable with and that you consider fit for the recording."

Analytical Strategy

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

The quantitative analysis examined the scores from the questionnaire scales (MPAS, PSS) and the scores of the behavioral patterns analysed in the videos. The data was analysed using IBM SPSS 24 for Mac.

The interaction videos consisted of a 15-minute interaction between the mother and infant. The videos were edited with Adobe Premiere CC to 5-s time base videos and were separated into 15-s of interaction episodes (Isabella & Belsky, 1991). The analysis considered the coding of three behavioral patterns: face-to-face interactions (FtF), and two three-step interactions: ThreeA (mother's response, infant's response, mother vocalization) and ThreeB (infant's vocalization, mother's response, infant's response). Each descriptor was marked and received a score from 1–5, from which an average score was calculated to give a single value for the statistical analysis (see Table 1). The minimum value represented asynchronous responses in interactions and a low level of engagement, and the maximum value represented synchronous occurrences and high level of engagement (Cohn et al., 1990; Isabella & Belsky, 1991).

| FtF (Cohn et al., 1990) | |

|---|---|

| Score | State |

| 1 | Negative: Facial or vocal expressions of anger, sadness, fussiness, or irritation. Intrusive handling or disinterest. |

| 2 | Look away: Neutral facial or vocal expression with gaze directed away from the baby or mother. |

| 3 | Attend: Neutral facial or vocal expression and gaze directed towards the baby or mother. |

| 4 | Low positive: Simple smile with corners of mouth turned up and cheeks raised, with gaze towards baby. Positive vocalizations. Interest expressions (Izard, Dougherty & Hembree, 1983), with gaze towards the mother. |

| 5 | High positive: Exaggerated facial or vocal expressions or smiling, combined with rhythmic vocalizations or body movements. Simple or broad smile from the baby. |

| ThreeA and ThreeB (Isabella & Belsky, 1991) | |

| Score | State |

| 1 | Negative: High asynchronous co-occurrences reflecting one-sided and intrusive behavioral exchanges. |

| 2 | Low negative: Asynchronous co-occurrences reflecting one side of unresponsive behavioral exchanges. |

| 3 | Attend/Neutral: Asynchronous and synchronous co-occurrence on the same three-step interaction –e.g. I vocalization, M attend, I not respond. |

| 4 | Low positive: Synchronous co-occurrences reflecting reciprocal behavior response. |

| 5 | High positive: High synchronous co-occurrences where M and I respond mutually with rewarding, reciprocal and affective behaviors. |

Note. Abbreviations: FtF, face-to-face interactions; ThreeA, three-step interaction (mother's response, infant's response, mother vocalization); ThreeB, three-step interaction (infant's vocalization, mother's response, infant's response); I, infant; M, mothers.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

This qualitative analysis considered the diaries and the follow-up interview. The initial analysis was based on the concluding code and analytical strategy of Study 1. However, based on the aims of the current study it was necessary to focus and explore mothers' experiences in daily life, and the elements that influence maternal attachment and mother–infant interactions. Additionally, the IV-diary and the follow-up interview considered the assigned condition. The final analysis considered an axial coding approach (Strauss & Corbin, 2015) for connecting the codes, the research tools, and the condition groups, and its results will be displayed according to the axial code. As in Study 1, the analysis was based on the IPA, and it considered the sensitive nature of the data collected. Data analysis was performed using NVivo 12 for Mac.

Results

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Scores were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > .05). The statistical analysis explored the difference between week1 and week2 (t1, t2, t3) (see Procedure) of the DVs under the condition groups. The scores of MPAS (t1, t2), PSS (t1, t2), QoA (t1, t2), AoH (t1, t2), and PoI (t1, t2) were averaged (AVG) and the difference (DIFF1) between t3 was calculated for testing the difference in means. The difference of the behavioral patterns (DIFF2) was calculated between t2, and t3 (see Table 2).

| IVs | DVs | Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| t1 | MPAS (t1, t2, t3) | |

| t2 | QoA (t1, t2, t3) | AVG (t1-t2) |

| t3 | AoH (t1, t2, t3) | |

| PoI (t1, t2, t3) | DIFF1 (AVG-t3) | |

| PSS (t1, t2, t3) | ||

| t2 | FtF (t2, t3) | |

| t3 | ThreeA (t2, t3) | DIFF2 (t2-t3) |

| ThreeB (t2, t3) |

Note. Abbreviations: t1, t2, t3, times of scores taken (see Procedure); MPAS, Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale; QoA, Quality of Attachment; AoH, Absence of Hostility; PoI, Pleasure of Interaction; PSS, Parental Stress Scale; FtF, face-to-face interactions; ThreeA, three-step interaction (mother's response, infant's response, mother vocalization); ThreeB, three-step interaction (infant's vocalization, mother's response, infant's response); DIFF1, difference value of MPAS, PSS, QoA, AoH, PoI; DIFF2, difference value of FtF, ThreeA, ThreeB 2; AVG, average of mean.

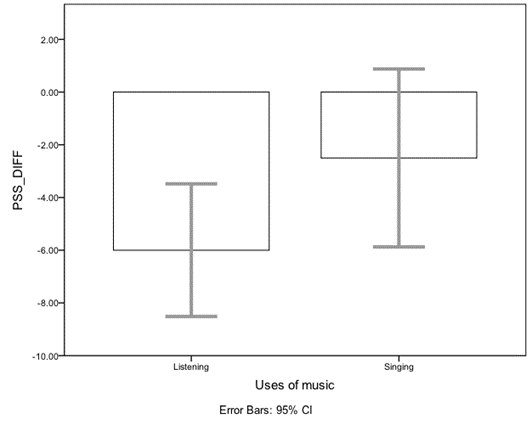

A total of eight one-way ANOVAs were conducted in order to prevent Type 1 error by doing multiple t-tests (Laerd Statistics, 2017) to compare the difference (DIFF1, DIFF2) between the condition groups under the variables. A significant mean difference was found in PSS_DIFF1, F(1,6) = 7.00, p =.038 (r = .538); and FtF_DIFF2, F(1,6) = 6.96, p = .03 (r = .537) (see Table 3). Therefore, the scores were tested with independent sample t-tests and paired sample t-tests to determine if there was a statistically significant mean difference under the condition groups, and between week1 and week2.

| F(1,6) | p | r | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPAS_DIFF1 | 1.080 | .339 | .153 |

| PSS_DIFF1 | 7.000 | .038* | .538 |

| QoA_DIFF1 | .067 | .805 | .011 |

| AoH_DIFF1 | .001 | .972 | .000 |

| PoI_DIFF1 | .045 | .839 | .007 |

| FtF_DIFF2 | 6.963 | .039* | .537 |

| ThreeA_DIFF2 | .894 | .381 | .130 |

| ThreeB_DIFF2 | 4.542 | .077 | .431 |

Note. Abbreviations: MPAS, Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale; QoA, Quality of Attachment; AoH, Absence of Hostility; PoI, Pleasure of Interaction; PSS, Parental Stress Scale; FtF, face-to-face interactions; ThreeA, three-step interaction (mother's response, infant's response, mother vocalization); ThreeB, three-step interaction (infant's vocalization, mother's response, infant's response); DIFF1, difference value of MPAS, PSS, QoA, AoH, PoI; DIFF2, difference value of FtF, ThreeA, ThreeB 2; *p<.05.

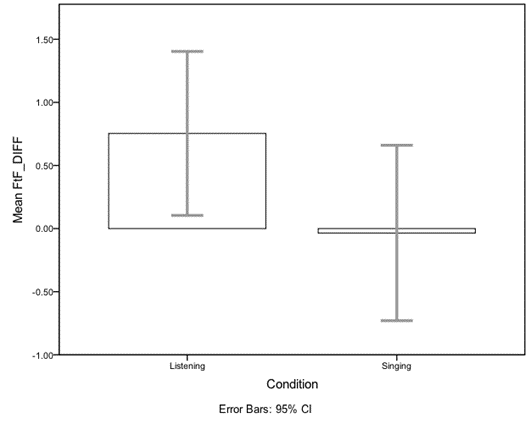

The independent t-tests showed that the listening PSS_DIFF1 score (M = -6.00, SD = 1.58) was higher than the singing mean PSS_DIFF1 score (M = -2.50, SD = 2.12), t(6) = -2.65, p = .03 (see Figure 4), while the listening FtF_DIFF2 score (M = .75, SD = .40) was higher than the singing mean FtF_DIFF2 score (M = -.03, SD = .43), t(6) = 2.63, p = .03 (see Figure 5).

Furthermore, the paired sample t-tests considered the week1 and week2 scores of PSS (PSS_AVG, PSS-t3) and FtF (FtF-t2, FtF-t3). Participants experienced more parental stress during week1(PSS_AVG) (M = 38.25, SD = 6.35) than week2 (PSS-t3) (M = 34, SD = 7.87), t(7) = -4.71, p = .002. However, there was no statistical significance between the FtF score of week1 (FtF-t2) (M = 3.65, SD = .32) and week2 (FtF-t3) (M = 4.01, SD = .37), t(7) = -1.76, p = .12.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

The findings are presented under the axial coding (see Table 4), which is based on the connection between the codes, the research tools, and the conditions.

| Week1 (control condition) | Week2 (experimental condition) |

|---|---|

| Motherhood in everyday

life: Motherhood experiences Maternal bonding Coping strategies |

Condition effect: Negative effect Positive effect |

| Music in mothers' everyday lives: Maternal singing Listening to music Selection of music |

Research experiences |

WEEK 1

MOTHERHOOD IN EVERYDAY LIFE

The main theme about motherhood in everyday life concerned elements that might influence mother–infant interactions and maternal bonding (Berry & Jones, 1995; Choi et al., 2005; Condon & Corkindale, 1998). Therefore, it retrieved first-hand information about how participants live their transition into motherhood (motherhood experiences), their sense of bonding with their infant (maternal bonding), and the strategies they employ to cope with stressful situations (coping strategies).

- Motherhood experiences. All of the participants stated

that motherhood had positive and negative associations.

Participants identified negative experiences, such as lack of

sleep, not having time for themselves, and difficulty meeting

role expectations. Participants who were employed (n=4) found it

stressful to sacrifice their jobs and professional careers in

order to take care of their infants.

I think that […] the worst thing of being a mum is not being able to sleep. It has been a big change for me and took a while for me to get used to it. And being honest, I haven't got used to it […] (P6, Control-diary)

[…] my mood fluctuates like a million thousand times […]. There are moments of absolute bliss, and there are moments of desperation, chaos, and everything, […] I needed a time for myself but sometimes [I feel] that is impossible, I am mom now. (P5, Control-diary)

Even if work meant time for themselves, it also meant missing something "special" about their infant, prompting a sense of guilt. Participants stated that having the sense of "not being a good mother" had impacted their self-esteem, making them feel unsure and unable to meet their infant's needs, specifically during distressed episodes.[…] now I'm back to work, and my husband is being promoted […] and he's gonna have to work late the next night, but I also had to work. And it's usually me that, if something goes wrong, I'm late for work, or I have to miss the shift. And that's annoying to me, because I'm the one that is missing out [on] money, or it looks bad for me at work, and things like that. Like why I must sacrifice my job or my career?! So, I was the one trying to find someone that just could babysit, I couldn't find anyone, until eventually, I talked to my neighbor, and she was like, "Oh, yeah, I'll take her", so. So, yes, that is always quite stressful […] (P4, Interview)

[…] sometimes I have to live in a world that is unbalanced, missing special moments with him […] then I suffered about that as well because I don't only have a crap job […], I'm a crap parent as well […], but yeah. [Looking at the baby] yes, you think I'm crap, do you? (P3, Interview)

Participants, however, also identified positive experiences such as having a successful routine during the day that includes playtime, bedtime, and housework. Additionally, they considered it rewarding to share intimate moments with their infant, specifically while breastfeeding, since they are the only ones able to do this with their infants.[…] he was either really tired or quite tired enough […] for whatever reason he wasn't having any of it […] I was still responding to him, but I couldn't find it in some way, in me, to deal with what he needs, it's a constant feeling of failure. (P6, Interview)

Such a blast! Bath time, book, and bed routine completed, William [pseudonym] in bed asleep by 9pm. (P8, Control-diary)

Nursing, absolutely! I think is because [it's] the only thing that only the two of us [do]. It's […] pretty much all my purpose. (P2, Interview)

-

Maternal bonding. Participants identified different

elements that make them feel "connected" to their babies during

everyday interactions. All participants described breastfeeding

as a unique and special activity and as an important way to bond

with their infant. Moreover, constantly making eye contact with

their infant facilitates communication and reassurance of the

infant's dislikes, likes, and emotional state.

Seven participants stated that the use of a sling and the constant touching and closeness associated with this makes them feel "connected" to their infants, and six stated that music during bedtime makes them feel close to their infant.I feel connected to my baby when [he] wakes up in the morning, he gives this look, like he's happy to see me, it's special and unique! (P1, Interview)

Conversely, the infant's distressed episodes were described as a moment when participants felt less "connected" with their infant, as well as when the infant was behaving "clingy" and wanted to be with the mother all the timeI would say babywear, so I use slings a lot. […] practically we are together all the time, and I think that helps us to connect […] (P2, Interview)

[…] if the baby is not happy, it won't sleep, can do anything […], you know there's something wrong, but I can't help her and I can't figure her out. (P4, Interview)

I just can't have her on me all the time, I just find that really suffocating and stressful. (P6, Interview)

- Coping strategies. Participants described it as

"soothing" when their partners were at home, giving them the

opportunity for a time out or for sleeping more. In addition,

they find it useful when family members help out with the

infant. This was supported by the comments of participants whose

families lived away, and who considered this a big disadvantage.

Significantly, all of the participants do activities for

themselves, such as attending fitness classes, and they

considered it necessary and "rewarding" to spend time with their

friends, specifically when they are able to take care of their

infant at the same time.

Not especially stressful but dad got up with him at six while I napped for an hour, it was heavenly! (P3, Control-diary)

I'm still recovering from the last week or so of work stress. I worked from home with my in-laws looking after Charles [pseudonym] so I got plenty of interaction through the day and felt like a bit of a better parent again. (P2, IV-diary)

It was a relaxed day, and it was lovely to spend time with friends. Sarah [pseudonym] has been very calm and happy and I can't think of any stressful situations from today. It felt so rewarding being able to enjoy a nice afternoon. (P5, Control-diary)

MUSIC IN MOTHERS' EVERYDAY LIVES

The following theme concerned the analysis of how mothers tend to use music in their everyday routines. It concerned mothers' interactions with their infants and the situations in which they might engage with music. It explored the main uses of music considered in this project, i.e. maternal singing and listening to music, and the analysis of the selection of music, i.e. when and in which context participants use self-selected music or infant songs. The information considered was retrieved from the second week diaries (control-diary) and the face-to-face interviews.

- Maternal singing. Participants use maternal singing to

prevent a distressed episode or to regulate their infant's mood.

Furthermore, similar to the findings in Study 1, participants

use maternal singing to get their infant's attention, mostly

during breastfeeding, and to share new knowledge such as letters

or parts of the body. Interestingly, participants tend to sing

along with tracks during the daytime while doing other

activities, but they only sing a cappella at bedtime, when they

are trying to "relax" their infant.

[…] then [sang] Peter Rabbit nursery rhyme to distract him from being grumpy just before nap as was overtired. (P7, Control-diary)

There are different songs that I sing her when we play versus the ones [we] use to [try] to get her to sleep. And I tried to keep [those] songs separate, or if I try to calm her, if she's crying or something like those, there's different songs, because I think for different moods. (P4, Interview)

It's more like in the quiet times [singing a capella], when I can actually bond with her […] I can go and sing a song to her, have a little bit more of intimate time. (P5, Interview)

Yes, we use it for bath time, and after bath time. Again, just for having something on [in] the background, meanwhile we sing along. Generally, not during bedtime, otherwise he gets distracted. (P2, Interview)

- Listening to music. Participants identified listening

to music more as background music, and they used it mostly

during the day during playtime or commuting, or when doing

housework. The participants had at least one favourite song to

listen to during distressed episodes for "relaxing" the infant.

Moreover, participants considered listening to music while

dancing with their babies an important activity for "getting

into a mood" and seven participants considered it important for

the family.

Yes, when I'm cooking for example, I might put on Alicia Keys or something like that, and she is usually sitting in her highchair while I'm cooking, and we will listen to music. (P2, Interview)

Playing two cellos and other music in the background. I should have put "our" song ("Can You Feel the Love Tonight") to him to help him nap when he was fighting it and I totally forgot because I was exhausted (bad night with snot and maybe tooth pain) and stressed (work). (P3, Control-diary)

We all love to dance! We just put some music on, and we start to dance around […] it could be just an R&B playlist on Spotify. We also have a pre-bedtime dance just her and me. (P8, Interview)

- Selection of music. This theme concerned the context in

which participants use self-selected music and infant songs

during the control condition or during their everyday lives.

Participants stated that their selection of music while

interacting with their infants depends on the infant's

preference and response. On one hand, participants tend to use

infant songs or classical music when they are with their infant

during activities in their daily routine, such as playtime,

feeds, or bath time. Moreover, participants find infant songs

effective for regulating their infant's mood and preventing

distressed episodes. On the other hand, participants tend to

listen to self-selected music when they are by themselves and

during other activities, such as commuting alone or doing

housework while the infant is having a nap.

There are a lot of Christmas songs that she likes, she likes to […] sing "Let It Snow", so she seems to like the happier ones. If I sing to her one kind of a slower, gentler one, unless she is about to go to sleep, she is just not very interested. She starts complaining, or whining, like she's bored. (P4, Interview)

An even with the classical songs, when she started to eat solid food, and she was in her highchair, one came on the radio, and it was a song from "Carmen", it was "Toreador" [humming the melody], and she likes that, and sometimes she only eats if you sing that, but even that is quite happy and bouncing. So, it seems, that [is] what she goes for. (P2, Interview)

Nursery rhymes seemed to be a good distraction again if he got grumpy […] Catching his attention with Disney songs and songs from The Sound of Music worked well. (P7, Control-diary)

Played the Arctic Monkeys and had a dance around in the morning while Sarah (pseudonym) was having a nap. (P8, Control-diary)

WEEK 2

This code concerned participants' experiences and statements in week2, in which participants were allocated into a condition group: singing or listening to music (see "Procedure"). During week2 the use of self-selected music was highlighted. Two participants stated that they used infant songs as self-selected music, since it was the music they felt more comfortable with. However, during the interview they shared that infant songs are the music they listen to all the time, and they could not remember what music they used to listen to before being mothers.

I really never put that music on that is really my taste of music […] I haven't listened too much to adult music since I am a mum […] I can't even remember what I like. (P5, Interview)

- Condition effect. This subtheme concerned participants'

experiences during week2. Specifically, it explored the

participants' context and motivations for using the condition

assigned. Participants under the singing condition felt more

connected to their infant, and they stated that, while singing

self-selected music to their infant, they had more eye-contact

and felt reassured of their infant's enjoyment. Moreover,

participants find it useful to sing self-selected music to

create intimate moments with their infant.

[…] and really look at her, and make eye contact, and sing to her, and feel like it's really a kind of way of reconnecting. Even if we have been together all day, it might not really be together, and focused more on her […] having that eye contact, sing a song and see her reaction, which actually has been really nice. […] it was quite sweet, I really feel pretty satisfied [to] see how she reacted like, "Oh, this is amazing!" (P8, Interview)

At the same time, participants under the listening condition stated that listening to self-selected music helped to make things easier, such as activities like bath time, bedtime, and meals, and they found it entertaining to see how their infants responded to the changes in rhythm or music genre.When we got in, I had a bath with Daisy (pseudonym), which was lovely. I sang some Les Miserables songs to her and it made it so peaceful, gorgeous, intimate time. (P5, IV-diary)

Being a first-time mother and stay at home the whole day sometimes can be a little bit boring, so listening to my music helped to make things easier, mainly during bath time! (P1, Interview)

In general, participants found self-selected music useful for regulating their own mood and their infant's, helping them to cope more easily and quickly with distressed episodes. Participants that used self-selected music expressed surprise that this music kept their infant distracted and prevented crying episodes, since previously they had only used infant songs for this purpose.I have a playlist which [starts] out with Snoop Dogg, and then it changed with a much more gentle acoustic [music], so I noticed that when it changed genre, he paid attention again, he noticed that it was something different, it was really entertaining to see his reactions to my music. (P8, IV-diary)

[…] then sang Adele "Someone Like You", on the way home in the car around 7pm as Oscar (pseudonym) was getting upset due to being exhausted after a busy day – this distracted him and allowed him to drift off. And I felt a lot less anxious than usual after this. (P7, IV-diary)

And I realized that putting [on] my own selection of music helped [him] to calm down and cope [with] the difficult situations faster, because it helped me to [calm] down. […] I realized that when he's about the scream or cry, if I put [on] music, it's like he forgets the bad situation and [comes] back to his good mood. (P1, Interview)

Also, they felt that seeing their infant's positive response towards their self-selected music was a bonding experience for them.Tried with solid food again at lunchtime and distracted Robert (pseudonym) with Alanis Morissette "Ironic" after lunch and prevented him from crying. This made me feel a lot less stressed, as usually I would worry a lot when he doesn't want to feed properly – this was a surprise too, normally I would have sung nursery rhymes, but this was very effective. (P8, IV-diary)

Well, he is very used to [listening] to me singing, because that's something we do all the time, but when I started to sing my own music, I find it quite funny, because he was really entertained. […] seeing his reactions, like that smile in his face or like seeing his eyes, that really makes me feel a little bit more connected. (P7, Interview)

-

Research experiences. This subtheme retrieved

information about how participants experienced the two-week

trial. Moreover, it collected first-hand information about how

participants found the experience of using their self-selected

music. Overall, participants considered the trial to be well

balanced and unintrusive, feeling a "natural flow". Two

participants, however, felt under pressure during the recording

of the IV-video (see "Measures and Data Collection" section),

since they felt that their infant was not responding to the

assigned condition as well as on previous days. All participants

considered the trial beneficial because they had not considered

the positive outcome of using self-selected music. Specifically,

participants considered the use of self-selected music an

effective tool for reinforcing their parental role, helping them

to cope more easily with distressed episodes, rediscover their

sense of Self, and boost their self-esteem.

[…] doing all the singing and all the intimate time with him helps me to feel okay about parenting […] I felt instantly very connected and bond with him. (P2, Interview)

I took Martha (pseudonym) upstairs, got her ready for bed and sang to her. I've really been paying attention to her response to my singing because of this study and it really does seem to give her so much pleasure. It's nice how my voice, which is not a great singing voice at all, can sound so perfect to my baby! (P3, IV-diary)

[…] the fact he is liking my singing, it's quite entertained itself. Because my husband, actually tried to sing to him one of the songs I sang, but he started to cry [laughs] it was the funniest! For me it was like, "OMG, I am actually doing something right. I just can't believe that someone thinks I'm great at singing." (P7, Interview)

[…] it made [me] think about singing more [of] my songs to him. Because that made me think about, "Oh, I used to like these things before." I mean, I used not to be a mother before, so I used to have my own [interests] and stuff. It was like remembering who I was. (P8, Interview)

I don't like to shout or explode, because it's always counterproductive and it always makes everything to turn out worst. So, yes, when I needed to get something out, I just sang my song! Sometimes [it's] like, it defuses things, and it releases something that isn't something that you don't wanna say, which is, "argh, you are driving me crazy right now!" (P5, Interview)

Yes […] it's […] like you feel that you are a person, and not just like a mom, when you only end up listening to his music [looks at baby]. And it was good to have the opportunity of singing a little bit of my own music. I mean, I always try to put some music on, but all of [a] sudden I was trying to remember what were the songs that I used to listen to [laughs]. So, it was good for my stress, really. (P1, Interview)

Discussion and Conclusions

This study aimed to explore if mothers' self-selected music (singing or listening) might facilitate maternal bonding. The study considered elements that might impact on the development of maternal attachment, such as parental stress, the subjective feelings of maternal attachment, and the analysis of behavioral patterns on mother–infant interactions. Adopting a mixed-method design allowed us to combine statistical analysis with the mothers' self-reported experiences and interpretations. In general, the study demonstrates that self-selected music has a positive impact on mothers' sense of well-being, mothers' and infants' mood regulation, and mother–infant interactions, facilitating maternal bonding. The study results suggest two main findings: a) music can reduce parental stress, specifically under the singing condition, and b) listening to the mother's self-selected music can enhance the quality of face-to-face interactions.

From the PSS data we can suggest that using self-selected music might reduce parental stress, specifically if the music is sung. This statement reflects previous research on the benefits of singing on emotional affect (Kreutz et al., 2004). Participants under this condition felt that singing self-selected music helped them carry out daily activities with their infants more easily. Moreover, participants stated during the trial that using self-selected music was something they left aside due to their new responsibilities as mothers; however, at the end of the trial they realized the beneficial impact on themselves and their infants. Consistent with previous literature, the motivations for using self-selected music, both individually and collectively, are related to the emotional impact of music and music affective responses (Batt-Rawden, 2010; Boer, 2009; Lamont et al., 2016). In particular, participants in the present study highlighted the ways in which self-selected music was an effective tool for regulating their own mood and their infant's. This suggests that self-selected music might have beneficial effects on the mother's emotional state. Moreover, these findings are interesting, since mood or mood regulation cannot be manipulated or controlled in research. Additionally, the study found that self-selected music might enhance the quality of face-to-face interactions between mothers and infants. In general, participants stated that having constant eye contact and seeing their infant's positive responses towards their music was something that made them feel more "connected" to them. Surprisingly, the quality of face-to-face interactions was higher in the listening condition than in the singing condition. A possible explanation for this, suggested by participants, was that the infant's response during the recording of the IV-video was untypical. Hence, the reason for this finding might be that participants under the singing condition experienced more difficulties in getting their infant's attention. Nonetheless, if visual expressions are more evident under the listening condition, it raises the question of how individuals' music responses are also affected by the dyadic interaction, which can be considered for future research. The current study offers initial insight into how mothers' self-selected uses of music might facilitate maternal bonding by promoting mothers' well-being and a better quality of mother–infant interactions. However, having a small sample size which only included participants from Sheffield (UK) raises questions about the reliability of the statistical analysis and the generalizability of the study. Notwithstanding, the study lays the groundwork for future research on the uses of music in mothers' everyday lives and on the use of music as a tool for enhancing maternal bonding. Hence, it is necessary that future research explores the social functions of music in family settings and considers the analysis of demographics for exploring whether cultural and societal factors might impact on the uses of music for facilitating maternal and family bonding.

GENERAL DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The general aim of the research project was to explore the extent to which mothers' uses of music might facilitate maternal bonding.

The findings of these studies suggest that mothers' and infants' musical responses are dependent upon each other. These findings are related to the musical processing elements of the "reciprocal feedback" model proposed by Hargreaves (2012). In this specific case, the music (self-selected, infant songs), listener (mother and infant), and context (environment; mother–infant interaction) are affected by the mother's need for nurture. Furthermore, the "reciprocal feedback" model offers an insight into the ways in which individuals' aesthetic responses to music are determined by cognitive and affective factors. This corresponds with our findings, suggesting that mothers like to use specific music due to their infants' enjoyment, and that they relate the use of this music to specific interactions with their infants, such as playtime or breastfeeding.

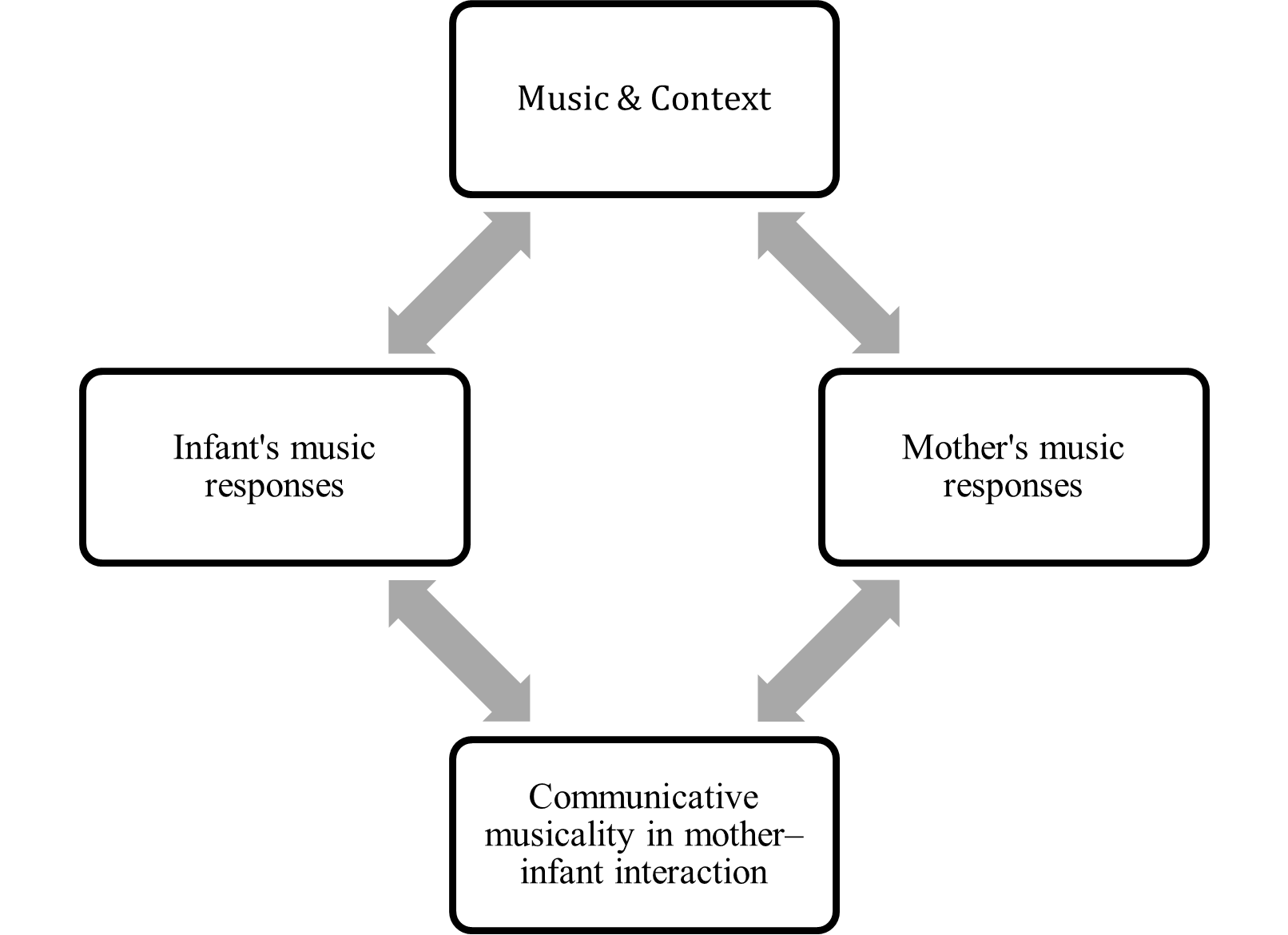

The initial observations of behavioral patterns on mother–infant interactions suggest that musical responses between mother and infant are intrinsic and unconscious (Malloch, 1999), and that they are dependent on the synchrony of behavioral patterns (Isabella & Belsky, 1991). The role of music in mother–infant interactions has been addressed in the theory of communicative musicality (Malloch, 1999; Malloch & Trevarthen, 2009). Malloch and Trevarthen (2009) suggest that the three parameters of pulse (the process of coordination between perception and production of communication), quality (changes over time of expressions of pitch, timbre, volume contours, and body movements), and narrative (the combination of pulse and quality which communicates and shares the sense of tenderness through time) are elements that are musical in nature. These elements allow mothers to communicate companionship to their infants by sharing meaningful emotional responses, and this correlates with the three affective behaviors of affectionate infant attunement proposed by Stern et al. (1985): beat, emphasis and intonation. When discussing the theory of communicative musicality, terms like "musicality" or "musical" should not be conceived as commonly understood. The musicality in mother–infant interactions makes it possible to "share time meaningfully together" (Malloch & Trevarthen, 2009, p. 5), since it should be perceived as a representation of the communication of cultural and social values between individuals. Because of this, it is proposed that a cycle of three elements (Figure 6) is observed during mother–infant interactions (context) while using self-selected music (music): a) the musical response of the mother's self-selected music influences their b) way to communicate and interact with their infant (communicative musicality), which at the same time influences c) the infant's musical response, impacting the mother's response to music, beginning the cycle all over again.

Fig. 6. Cycle of three elements proposed where the mother's musical response influences the infant's musical response by the communicative musicality between both.

Equally important, the data reported in the studies supports the assumption that using music and musical responses, especially of self-selected music, during mother–infant interactions might facilitate maternal bonding. Mothers use music as a tool for reassuring self-identity, mood regulation, and for coping more easily during distressed episodes. As previous research suggests, these are important elements for mothers maintaining their sense of well-being, and they impact on the quality of mother–infant interactions, hence facilitating a secure maternal attachment (Currie, 2009; Steele et al., 1996). The process is as follows (see Figure 7):

Due to time constraints preventing further recruitment, our sample size was small and only included women living in England. It is therefore necessary to repeat the study with a larger sample and more diverse demographics in order to improve the reliability of the findings. However, these analyses were exploratory in nature and still provide valuable initial data on the uses of music during mother–infant interactions, considering the mothers' perspective, which can sometimes be neglected by society. As the mothers stated, motherhood can be challenging because it is a full-time job with no breaks, hence it is necessary to draw upon effective strategies that might help mothers living the transition into motherhood.

Overall, the conclusions contribute to the understanding of the uses of music within the context of early motherhood. They also contribute to the understanding of the impact of mothers' self-selected music on mother–infant interactions and maternal bonding. Furthermore, understanding the effects of music for facilitating maternal bonding might contribute not only to music research but also to the provision of strategies to help carers with maternal bonding interventions. Future studies could consider the influence of culture, family structures, parental interactions, and parenting styles in order to encourage families by offering specific advice about how they can promote bonding between family members by using music in everyday interactions. Children have the right to achieve their maximum potential, but for that it is necessary to pay attention to the influence of their parents or principal caregivers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the women and babies who participated in this project. The author would also like to thank Renee Timmers for her constant advice and support during the project, Ashley Warmbrodt and Rory Kirk for helping with formatting and proofreading the present paper, and Sandra Trehub for her advice with the publication process. Likewise, the author is deeply thankful to her family for all their support, and for inspiring her to complete the project. Also, a special thanks to Tezcan for being the most patient and understanding of them all. This article was copyedited by Bridget Coulter and layout edited by Jonathan Tang.

NOTES

-

Correspondence can be addressed to: Verna Vazquez-Diaz

de Leon, Independent Scholar, vertiefel@gmail.com.

Return to Text

REFERENCES

- Adorno, T. W. (1976). Introduction to the sociology of music. New York: Seabury.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Barnett, R. C., & Baruch, G. K. (1985). Women's involvement in multiple roles and psychological distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.135

- Batt-Rawden, K. B. (2010). The benefits of self-selected music on health and well-being. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37, 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2010.05.005

- Batt-Rawden, K. B., & DeNora, T. (2005). Music and informal learning in everyday life. Music Education Research, 7, 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800500324507

- Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). The parental stress scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595123009

- Boer, D. (2009). Music makes the people come together: Social functions of music listening for young people across cultures. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1). London: The Hogarth Press.

- Choi, P., Henshaw, C., Baker, S., & Tree, J. (2005). Supermum, super wife, supereverything: Performing femininity in the transition to motherhood. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 23(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830500129487

- Cohn, J. F., Campbell, S. B., Matias, R., & Hopkins, J. (1990). Face-to-face interactions of postpartum depressed and nondepressed mother–infant pairs at 2 months. Developmental Psychology, 26(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.26.1.15

- Condon, J. T., & Corkindale, C. J. (1998). The assessment of parent-to-infant attachment: Development of a self-report questionnaire. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 16(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646839808404558

- Crittenden, A. (2001). The price of motherhood: Why the most important job in the world is still the least valued. New York: Henry Holt.

- Currie, J. (2009). Managing motherhood: Strategies used by new mothers to maintain perceptions of wellness. Health Care for Women International, 30(7), 653–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330902928873

- Davidson, R. J. (1994). Asymmetric brain function, affective style, and psychopathology: The role of early experience and plasticity. Development and Psychopathology, 6(4), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004764

- De l'Etoile, S. K. (2006). Infant behavioral responses to infant-directed singing and other maternal interactions. Infant Behavior & Development, 29, 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.002

- De L'Etoile, S. K. (2012). Responses to infant-directed singing in infants of mothers with depressive symptoms. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39, 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.05.003

- DeNora, T. (1997). Music and erotic agency: Sonic resources and social-sexual action. Body & Society, 3, 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X97003002004

- DeNora, T. (2000). Music in everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489433

- DeNora, T. (2010). Emotion as social emergence: Perspectives from music sociology. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 159–183). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199230143.003.0007

- Edwards, J. (2011). The use of music therapy to promote attachment between parents and infants. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38, 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.05.002

- Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2017). Associations between singing to babies and symptoms of postnatal depression, wellbeing, self-esteem and mother–infant bond. Public Health, 145, 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.01.016