whosampled.com is a website that hosts user-compiled lists of samples, covers, and remixes of pre-existing music. I first happened upon this website a few years ago, while completing research for another project 2 and was intrigued to find a peculiar claim: That John Williams had "sampled" the music of Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in the score for Jaws (1975). If interpreted literally, of course, this assertion is clearly false; Williams did not sample—that is, extract and manipulate sound from a recording of The Rite—in the soundtrack for Spielberg's iconic film. Nevertheless, this assertion should not simply be dismissed. Though Williams does not quote Stravinsky's music directly, through digital or analog means, a contributor to this website does identify a case of stylistic allusion; moments of the Jaws score are at least evocative of Stravinsky's Rite, and it is likely that Williams found inspiration in the music of the modernist ballet, even if the two pieces do not feature precisely the same combination of notes and rhythms.

My fortuitous stumble upon whosampled.com left me with several questions: How reliable is the user-generated data on this website? Which types of entries are most likely to be accurate, and why? And lastly, are entries that are not, strictly speaking, "correct," nevertheless informative? That is, do most examples that fail to identify clear cases of musical borrowing—like the Jaws ➔ Rite of Spring example above—highlight meaningful similarity between different works? To answer these questions, I studied hundreds of examples housed on whosampled.com, and listened to each carefully to evaluate their accuracy. This article shares some of the most instructive findings gleaned from combing the information found on the site. After providing a brief overview of how the information on whosampled.com is organized, the article is organized into four primary sections. The first three sections examine every reported sample in the music of three contemporary artists known for producing nostalgic, stylistically familiar hits: Bruno Mars, Janelle Monáe, and Dua Lipa (respectively); each corpus makes for an informative case study. The fourth offers a brief discussion of what can be learned from a comprehensive study of the reported samples in Classical music that appears on whosampled.com— a website primarily designed to discuss forms of borrowing in popular music. The article concludes with summative thoughts about the accuracy of this website and its usability as a resource. 3

HOW WHOSAMPLED.COM IS ORGANIZED

All entries on whosampled.com include recordings of two musical works—the piece from which the reported sample is taken, and the piece that incorporates the reported sample—enabling a user of the site to compare the two excerpts with ease. All samples are classified by manner in which material from another source is used, and the elements borrowed (which instruments and or voice parts are adapted). To answer the former question, a distinction is made between two types of samples: "Direct," true samples, in which sound from another recording is digitally copied into a new context; or "Interpolated (Re-Recorded)" samples, which most typically feature a new performance of borrowed material. To answer the latter, a wide range of categories are provided, six of which appear regularly. Table 1 shows that all samples are described with a single sentence that includes one segment of each column. Appendices A and B provide definitions of the common categories of samples, along with two didactically clear, accurately identified examples of each that appear on the website.

| Type of Sample | of | Material Sampled (Six Common Categories) 4 |

|---|---|---|

| "Direct sample… "Interpolation (replayed sample)… | …Hook/Riff" …Vocals/Lyrics" …Multiple elements" …Drums" …Bass" …Sound effect/Other/Unspecified" |

CASE 1: BRUNO MARS

American pop singer Bruno Mars (b. 1985) has enjoyed remarkable success as an artist with songs that revel unabashedly in familiar styles ranging from 1960s doo-wop to 1990s hip hop. When he first became a household name in the early 2010s, though such backward-gazing hits were not uncommon, few artists who consistently found their songs at the top of the charts were so explicit in their practice of pastiche; his sustained popularity has surely persuaded other artists to abandon the pretense of writing on a "clean slate" and make a career of producing unapologetically retro singles. Given Bruno Mars's enthusiastic embrace of earlier styles, it is likely unsurprising that several users of whosampled.com have identified borrowed material in his work. There are, at the time of writing, 13 discrete entries reporting "samples" in songs in which Mars played a significant role as a writer and performer (either primary or guest). Of these 13 examples, seven are classified as "direct," literal samples, while six are listed as "interpolations" ("traditional," analog quotations). Each will be discussed in turn, followed by a brief exploration of some songs not featured on whosampled.com that seem likely candidates for inclusion.

Direct Samples in the Music of Bruno Mars

All seven reported examples of direct sampling in the music of Bruno Mars are shown in Table 2 below. "Nothin' on You," "Just the Way You Are," and "It Will Rain" all plainly feature a drumbeat sampled from the sources listed. "Natalie" and "Young, Wild & Free" seem likewise to borrow the beats indicated, but somewhat less clearly. In the former, the beat is processed to have a distant-sounding echo; in the latter, a tambourine sound is added, and the possibility exists that the drum sounds were re-recorded rather than sampled directly. Nevertheless, the source of each is identified accurately. The alleged sampling of "multiple elements" from a mid-century Jazz tune in "Old & Crazy" is sonically obscured in a busy texture, yet this assertion is apparently correct, as the sample is acknowledged in the liner notes of the album on which this track appears (Unorthodox Jukebox). The only one of these seven claims open to some debate is the use of the "Orchestra Hit" in "Finesse." 5 This oft-sampled sound clearly appears in the song, but it is uncertain if it was sourced directly from the original library listed. Given the near ubiquity of this effect in popular music of the 1980s and 1990s, it could have been sampled from any number of recordings, or even played on a commercially available synthesizer.

| Bruno Mars Song | Material sampled | Source |

|---|---|---|

| "Nothin' on You" (2010) w/ B.o.B | Drums | Joe Tex, "Papa Was Too" (1966) |

| "Just the Way You Are," (2010) | Drums | Ralph Vargas and Carlos Bess, "Ode to Mr. Bess" (1994) |

| "Young, Wild & Free" (2011) w/ Wiz Khalifa and Snoop Dog | Drums | Tom Scott and the L.A. Express, "Sneakin' in the Back" (1974) |

| "It Will Rain" (2011) | Drums | Funkadelic, "Good Old Music" (1970) |

| "Natalie" (2012) | Drums | Nina Simone, "See Line Woman" |

| "Old & Crazy" (2012) w/ Esperanza Spalding | Multiple Elements | Dicky Wells and His Orchestra, "Japanese Sandman" (1955) |

| "Finesse" (2016) w/Cardi B | Multiple Elements* *really a Sound Effect | Fairlight CMI, "ORCH 5" ("Orchestra Hit" Sound) |

Interpolations in the Music of Bruno Mars

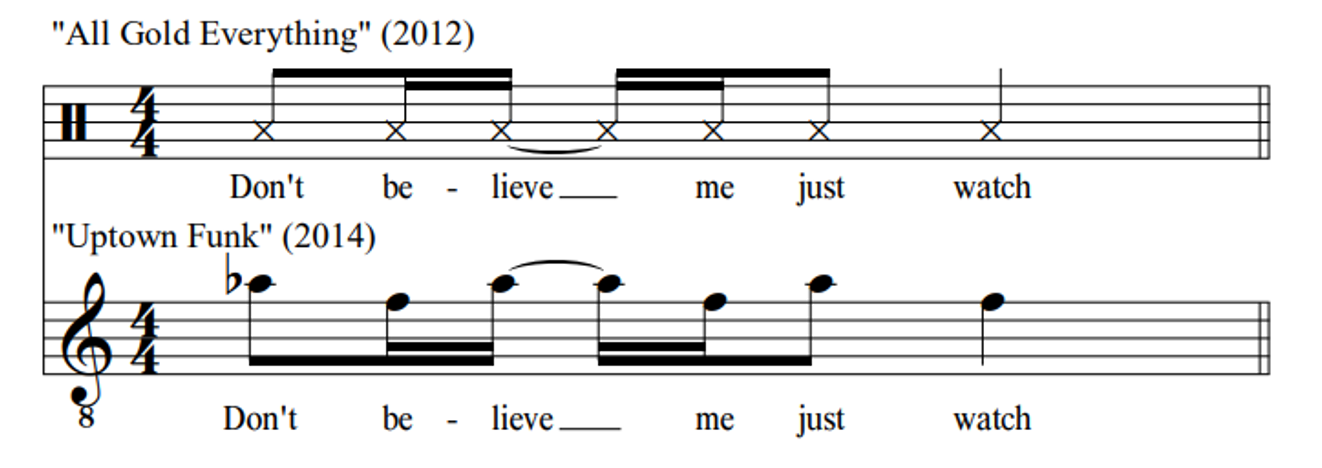

Many of the user-identified "interpolations" in the music of Bruno Mars (Table 3) also present relatively clear cases of musical borrowing. Three of the most straightforward examples on the above list are quotations of rapped or spoken vocals. Although there is no clear melody in any of these excerpts, Mars preserves the rhythm and metrical placement of the words of each of the borrowed passages. In "The Lazy Song," Mars glosses the title line of Cali Swag District's "Teach Me How to Dougie;" see in Figure 1 that these six syllables are spoken or sung (respectively) on "3-e-&-a-4-e" of the bar in both songs. Similarly, in "Uptown Funk," the line "Don't believe me just watch" clearly references Trinidad Jame$ song "All Gold Everything;" these words are intoned with the same "1 & a (2) e & 3" rhythm (See Figure 2) in each context, and this line is repeated at least five times in a row in both songs, forming the basis of an entire section or stanza. 6 The spoken-word bridge of "Uptown Funk" is likewise derived from an earlier source. See in Figure 3 that the opening of the Gap Band's "I Don't Believe You Want to Get Up and Dance (Oops)" must surely form the basis of this section. Not only are the rhythms of the spoken word vocals identical (give or take an interjection of "I said") but the bass line that accompanies each is also similar; both feature a minor pentatonic scale with a shared subtonic anacrusis leading to a strong tonic downbeat.

| Bruno Mars Song | Material Reportedly Sampled | Source |

|---|---|---|

| "The Lazy Song" (2010) | Vocals/Lyrics | Cali Swag District, "Teach Me How to Dougie" (2010) |

| "Young, Wild & Free" (2011) with Wiz Khalifa and Snoop Dog | Multiple Elements *really Vocals/lyrics | YG feat. Ty$, "Toot It and Boot It," (2010) |

| "Treasure" (2012) | Hook/Riff | Breakbot feat. Irfane, "Baby I'm Yours" (2010) |

| "Uptown Funk" (2014) w/Mark Ronson | Vocals/Lyrics | Trinidad Jame$, "All Gold Everything" (2012) |

| Vocals/Lyrics | The Gap Band, "I Don't Believe You…" (1979) | |

| "Straight Up and Down" (2016) | Multiple Elements | Shai, "Baby I'm Yours" (1992) |

The assertion that "Young, Wild & Free" reworks "multiple elements" from YG feat. Ty$, "Toot It and Boot It," is likewise mostly correct, but only the vocal melody of the song is adapted. See in Figure 4 that the melody is borrowed directly, though in a different key and with new text added. This was presumably identified as an interpolation of multiple instruments because this melody forms the basis not only for the vocals of "Young, Wild & Free," but also for some of the newly composed piano parts that echo the vocal line; put another way, multiple elements of a new song are created from what was a single element in the source. Outside of the shared vocal melody, the instrumental context of each is otherwise strikingly different. As seen on the chart of direct samples above, the drum beat in "Young, Wild & Free" is borrowed from another source entirely, and the minor-mode bass line that accompanies the untexted vocal melody in "Toot it and Boot It" is abandoned and replaced by bright piano chords that recontextualize the melody in the major mode.

The two remaining "interpolations" listed in Table 3 above require further exploration. Curiously, both examples reportedly adapt material from different songs named "Baby I'm Yours." Compare the opening bass lines and harmonies of Shai's "Baby I'm Yours" (1992) with Bruno Mars' "Straight Up & Down" (2016) in Figure 5, and—more crucially—listen to the two, as the shared "feel" from a similar tempo with swung 16th notes is not easily captured with graphic notation. The respective bass riffs emphasize similar rhythmic patterns, the chords appearing on the downbeats match, and the harmonic rhythm is the same. Further, the soft, mellow keyboard sound in "Straight Up & Down" should immediately remind the listener of an early 1990s R&B ballad. Beyond the respective opening progressions, the songs have identical formal plans. Though the order of sections is fairly paint by number in each (two verse-chorus cycles followed by a bridge and final repeating chorus), there are nevertheless some meaningful commonalities; namely, both songs return to their respective "stable" verse chord progressions in the chorus after a brief, more chromatic departure from it in the transition from the former to the latter.

Despite these many similarities, it is difficult to determine if Bruno Mars and his creative team used this song as their model in composing "Straight Up & Down," in part because "Baby I'm Yours" is not terribly distinctive. Countless other songs feature a passage like the one shown above in Figure 5—a fact Ed Sheeran was all too keen to point out in his defense when he was accused of copying this very progression from Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get it On" (1973) in his hit "Thinking Out Loud" (2014). (Both songs feature I iii-or-I6 IV V at precisely this rhythm; fortunately for Sheeran, a federal jury agreed with his assessment, deciding the case in his favor.) 7 Further, though it is tempting to find significance in the features they share that are not dime-a-dozen on the pop charts, there is little in the design of "Baby I'm Yours" to distinguish it from other R&B crooning songs of the period. In fact, Shai's song seems to follow the formula of Boyz II Men's highly successful "End of the Road" (1992) released several months earlier, down to the smallest detail, including the now-cliché partially spoken bridge. These intimate, spoken-word passages are so strongly associated with 1990s R&B that such a section seemingly must be included in any latter-day pastiche (or parody) of this style. 8 So given the lack of distinctiveness of Shai's "Baby I'm Yours," there is not sufficient evidence to argue that "Straight Up & Down" borrows from this song in any meaningful way.

The reported sample of the Breakbot (featuring Irfane) song "Baby I'm Yours" in "Treasure," however, is somewhat more convincing. Compare the respective opening and closing lines of the chorus of each song in Figures 6a and 6b. For ease of comparison, the two songs are notated in the same key; even though "Treasure" is a step lower than notated here, there are enough shared elements to posit—though not "prove"—that Bruno Mars and his team used this song as a model in composing "Treasure." Not only is there a great deal of melodic similarity, but the chorus of each ends with the very same V13-type harmony: the notes of a subdominant chord with ^5 in the bass and ^3 in the melodic voice. Further, two the songs are in precisely the same style (Neo- or Nü-Disco), making it seem likely that one did indeed inspire the other.

Other Borrowing in the Music of Bruno Mars

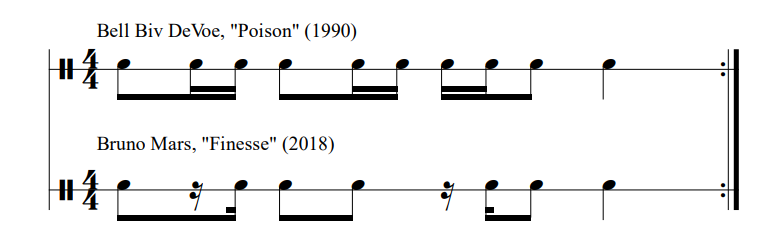

Given the regularity with which Bruno Mars alludes to older styles, one might expect to see more reported examples of interpolation on whosampled.com. There are two potential entries that are—at least to me—surprisingly absent from the site: "Locked Out of Heaven" (2012) and "Finesse" (2016). When I first heard the opening passage of each of these songs, I was momentarily "fooled" into thinking they were recorded in an earlier decade. 9 Noticing the distinctive stylistic blend of reggae and rock in the introduction of "Locked Out of Heaven", I assumed that I was listening to a song by The Police with which I was previously unaware. 10 Only upon hearing Bruno Mars's voice (rather than Sting's) did I realize that the song was a product of 1980s nostalgia rather than an artifact of that decade. In "Finesse", the aforementioned "orchestra hit" sound is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to capturing the sound of this period. It is a clear pastiche of the "New Jack Swing" style. I was initially convinced that it was an early 1990s hip hop/R&B song, in part because the song begins with a clear allusion to what is perhaps the best remembered song in this style: Bell Biv DeVoe's "Poison" (1990). Both songs begin with several repetitions of a drum pattern on a snare-type sound. See in Figure 7 that this is not a verbatim quotation (nor literal sample), but when one hears the opening drum riff of "Finesse," it's difficult not to think of "Poison."

CASE 2: JANELLE MONáE

Janelle Monáe (b. 1985 as Janelle Monáe Robinson) is an American musical artist—and more recently, an actor—who creates music that can be characterized by nostalgia for the days of soul, funk, and especially "synth funk" (à la Prince, her/their sometime mentor). As one might expect, on whosampled.com, there is a long list of reported samples in tracks on which she/they is the primary artist: Seven direct samples and 10 interpolations.

Direct Samples in the Music of Janelle Monáe

As was the case with the music of Bruno Mars, the direct samples reported in Monáe's music (Table 4) appear to be largely correct and clear. The only one that demands commentary is the reported sample of the opening drum riff of Michael Jackson's "Rock With You" in Monáe's "Locked Inside." Both passages feature a measure of percussion with precisely the same rhythm (One tri-po-let Two e, Three e and a Four e), yet this passage is not a literal sample; see in Figure 8 that different parts of the drum set are used. Although this is not a "true" digital sample, the reader may decide whether the motive in Monáe's song is a reference to Michael Jackson's iconic song, or if the resemblance between the two passages is simply a coincidence. 11

| Janelle Monáe Song | Material Reportedly Sampled | Reported Source |

|---|---|---|

| "Sincerely, Jane" (2008) | Vocals/Lyrics | The Mohawks, "The Champ" (1968) |

| "Locked Inside" (2010) | Drums | Michael Jackson, "Rock With You" |

| "Neon Gumbo" (2010) | Multiple Elements | "Many Moons," Song from earlier JM album |

| "Faster" (2010) | "Direct Sample" (Unspecified) | Tokyo Jihen 能動的三分間 (2009) |

| "Hum Along and Dance (Gotta Get Down)" (2016) | Vocals/Lyrics | The Jackson 5, "Hum Along and Dance" (1973) |

| "Don't Judge Me" (2018) | "Direct Sample" (Unspecified/Sound Effect) | Radiohead, "Climbing Up The Walls" (1997) |

| "Django Jane" (2018) | Vocals/Lyrics | Janelle Monáe, "Screwed" (2018) *same album as "Django Jane" |

Interpolations in the Music of Janelle Monáe

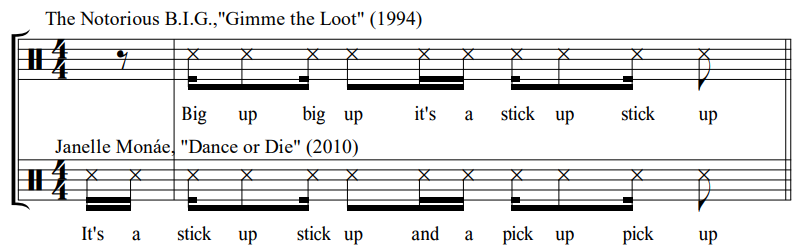

Of the ten interpolations reported in Monáe's music (Table 5), however, only a small minority present clear cases of musical borrowings. The reported quotations of rapped lines in "Dance or Die" and "Dance Apocalyptic" are the least controversial of the bunch. See in Figure 9 that although Monáe raps slightly different words than those appearing in Biggie's hit, the identical rhythm and comparable repetitions of two-word phrases in her/their "Dance or Die" make it clear that she/they is "riffing"—or perhaps signifyin(g)—on "Gimme the Loot." 12 Likewise, Juicy J's "Bandz a Make Her Dance" seems to be the source of the repeated opening line(s) of her/their "Dance Apocalyptic" (Figure 10). Though the rhythm is not precisely the same, someone on Monáe's creative team must have been aware of this song; like Bruno Mars' quotation of "Teach Me How to Dougie" in "The Lazy Song," Monáe tips her/their hat to a song that was on the charts while "Dance Apocalyptic" was in production.

| Janelle Monáe Song | Material | Source |

|---|---|---|

| "Many Moons" (2007) | Vocals/Lyrics | Pointer Sisters, "Pinball Number Count" (1977) |

| "Sincerely, Jane" (2008) | Hook/Riff | Stevie Wonder, "Superwoman" (1972) |

| Vocals/Lyrics | Mavin Gaye, "Save the Children" (1971) | |

| "Say You'll Go" (2010) | Hook/Riff | Debussy, "Claire de Lune" (1903) |

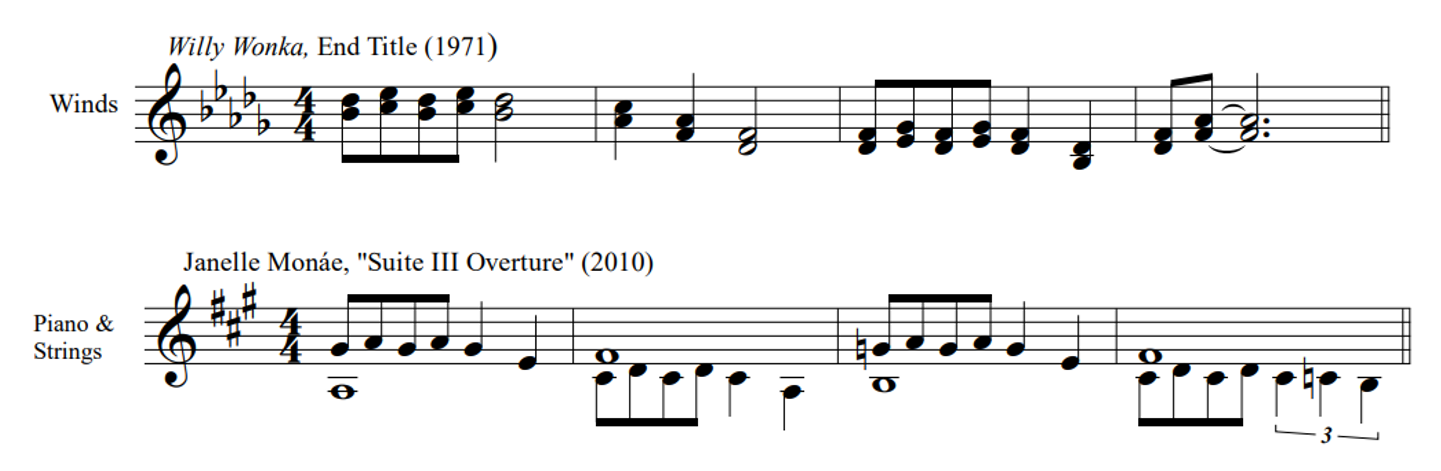

| "Suite III Overture" (2010) | Hook/Riff | Willy Wonka End Title (1971) |

| "Wondaland" (2010) | Vocals/Lyrics | Thomas Ken, "Praise God from whom all blessings flow" (1674) |

| "Dance or Die" (2010) w/Saul Williams | Vocals/Lyrics | The Notorious B.I.G., "Gimme the Loot" (1994) |

| "Dance Apocalyptic" (2013) | Vocals/Lyrics | "Bandz a make her Dance" (2012) |

| "I Got the Juice" (2018) w/Pharrell Williams | Multiple Elements | Vanity 6, "Nasty Girl" (1982) *Written by Prince |

| "Pynk" (2018) | Vocals/Lyrics | Aerosmith, "Pink" (1997) |

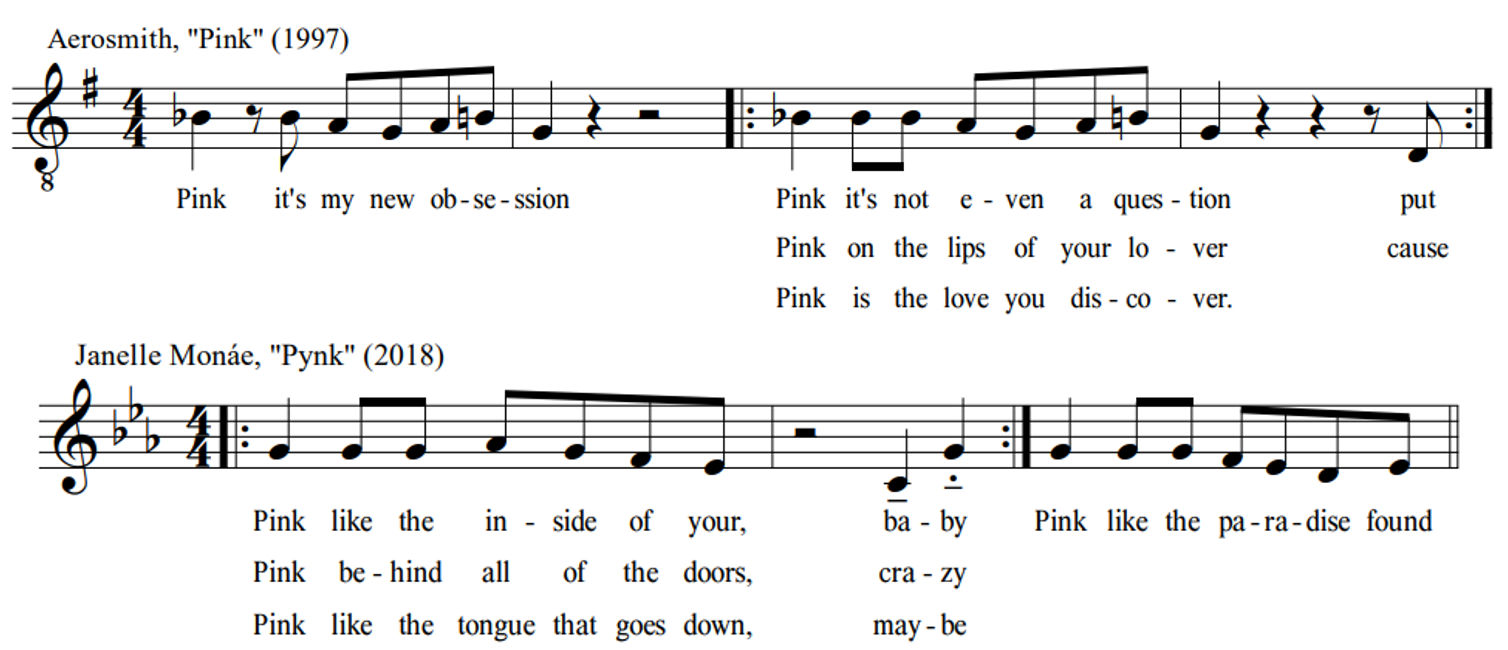

At least four of the other reported interpolations are likely "correct" identifications of borrowing, or at least allusion. In Monáe's "Sincerely, Jane"—which (see Table 4 above) includes one clear direct sample from a soul record already—the spoken words "live your life" may indeed reference Marvin Gaye's "Save The Children," and the synth line is likely an homage to Stevie Wonder's "Superwoman" (see Figure 11). Yet the material reportedly borrowed in both cases, though plenty similar, is not distinctive enough to argue unequivocally that one is the source of the other. The same can be said of the passages of Monáe's "Many Moons" that sound like the Pointer Sisters' "Pinball Number Count" (Figure 12); the resemblance is striking—a fifteen-note minor-pentatonic segment with identical rhythm and similar contour—yet one might hesitate to posit (without qualification) that Monáe paraphrases a tune from such an early vintage of Sesame Street. Lastly, though it is uncertain if Monáe (consciously) had Aerosmith's "Pink" in mind when she/they drafted "Pynk," the two songs certainly have a lot in common. See in Figure 13 that the first verse of each comprises four two-bar phrases; each begins on the word "Pink" and features a descending mediant to tonic melodic figure. 13

The remaining examples demand further scrutiny. First, although it is clear that "Wondaland" includes allusions to Christian worship music, it is misleading—and probably incorrect—to cite a single hymn as the source of the word "Hallelujah." Similarly perplexing are the other two reported samples from sources beyond the popular music canon. The "Suite III Overture" is at least superficially similar to the Willy Wonka end title music (Figure 14), but to suggest that the former borrows from the latter seems a bit of a stretch. Likewise, the reported interpolation of Debussy's "Claire de Lune" in Monáe's "Say You'll Go" is partially correct. If one were to listen only to the segments at the time stamps provided (Figure 15), though reasonable to infer that one inspired the other, it's a bridge too far to call one a quotation—much less a sample—of the other. Later in "Say You'll Go," however, there is an extended, "verbatim" quotation of "Claire de Lune." Though transposed a half-step higher, and other layers are added atop it, the borrowed material from Debussy is otherwise unchanged. One wonders why the user who created this entry did not supply these time stamps instead of, or in addition, to the one notated in Figure 15.

Other Borrowing in the Music of Janelle Monáe

When discussing intertextuality in the music of Janelle Monáe, it's hard to avoid the aforementioned (tiny, purple-clad) elephant in the room: Prince. The one example from Table 7 that was not discussed in the above paragraphs is Monáe's "I Got the Juice," which reportedly includes an interpolation of "Nasty Girl" by Vanity 6—a track that Prince composed and imbued with his characteristic, synth-heavy "Minneapolis sound." "I Got the Juice" doesn't exactly quote "Nasty Girl," but it does feature both similar rhythmic patterns and alternation between tonic and subtonic chords in the same key. 14 Instead, it's most accurate to say that "I Got The Juice" simply sounds like a song that Prince might have written. The same can be said—to a much greater extent—with "Make Me Feel" (2018) from the same album. There is a (spurious, unverified) rumor that Prince had a role in composing "Make Me Feel" before his death in 2016; 15 whether or not this is true, it is surprising that there aren't more reported examples of interpolations of Prince songs on whosampled.com, especially given Monáe's clear debts to his music.

CASE 3: DUA LIPA

English pop star Dua Lipa's (b. 1995) highly decorated record, Future Nostalgia (2020) has as an unusually apt album title, perfectly describing her project of repackaging the sounds of 1970s-1990s pop for a new listening public. Many of her songs are outright pastiches of styles from these decades; one especially clear example is her hit, "Physical" (2020), which comes complete with an unapologetically campy Jane Fonda 1980s workout video. Although familiar styles loom equally large in Dua Lipa's music as they do for Bruno Mars or Janelle Monáe, users of whosampled.com have only identified four tracks on which she is the primary artist that reportedly include samples of other songs. (More will surely follow, given Lipa's relatively recent rise to fame.) 16 Nevertheless, comparing these four examples provides an instructive window into the practices of her creative team.

Direct Samples and Interpolations in the Music of Dua Lipa

Table 6 provides a list of the four reported samples in Dua Lipa's work. The first entry is a straightforward, direct sample; Dua Lipa's "Love Again" clearly does borrow the lo-fi trumpet melody from the 1932 tune "Your Woman." One wonders if the producers of "Love Again" were aware of Lew Stone's nearly ninety-year-old record, or if they were familiar with it through the 1997 White Town track of the same title that likewise incorporates a sample of this passage; regardless, the source is correctly identified. The next entry on the table is likewise accurate. Lipa's song "Genesis," according to a whosampled.com user, includes a "replayed sample of vocals/lyrics" from the first chapter of the Old Testament. Although it may seem peculiar to use the term "sample" to describe a paraphrase of biblical text, the opening lyrics of this song are undeniably borrowed from the first verses of the Bible. 17

| Dua Lipa Song | Reported Sample | Reported Type |

|---|---|---|

| "Love Again" (2020) | "Your Woman" (1932), Lew Stone & the Monseigeur Band | Direct Sample of Hook/Riff |

| "Genesis" (2017) | The Book of Genesis, from the Bible | Interpolation (Replayed Sample) of Vocals/Lyrics |

| "Break my Heart" (2020) | "Need You Tonight" (1987), INXS | Interpolation (Replayed Sample) of Hook/Riff |

| "Homesick" (2017), featuring Chris Martin | "Everglow" (2016), Coldplay | Interpolation (Replayed Sample) of Hook/Riff |

Neither the third nor the fourth entry, however, is a clear example of a quotation or paraphrase from a single source. Each reveals a somewhat more complex story. The suggestion that Lipa's "Break My Heart" borrows from INXS's "Need You Tonight" is not without merit. Compare the vocal melody of the chorus of "Break My Heart" to the opening guitar riff of its reported source in Figure 16. Both melodies, if only for a moment, are quite similar, featuring a two-bar segment with identical rhythm and a melody constructed with the first three degrees of a minor scale. Despite the clear melodic similarity, the songs have little else in common. It seems unlikely, therefore, that one borrows directly from the other. Instead, this is a case of two songs drawing from the same stylistic well rather than outright quotation or sampling. If a single source for both songs can be identified, it is most likely the opening bass riff from Chic's "Good Time," which has provided inspiration for countless artists looking to harness the dance-floor fun of a "funky" disco track. Compare in Figure 17 the basslines in songs by a rock band (Queen), a country artist (Luke Bryan), and a pop star (Dua Lipa) that all begin with remarkably similar repeated ostinati, each of which include multiple quarter note hits on low E.

The last of these reported samples highlights an even more striking resemblance between two passages than did the previous example, but once again, I will argue that it is misleading to identify this as a quotation. See in Figure 18 that the piano introduction to Lipa's "Homesick" has obvious similarities to the first bars of Coldplay's "Everglow." Though the key is different, both the chord progression and harmonic rhythm are identical. Furthermore, the respective first and third measures of each feature similar ^6-^5 patterns in the melody, while the even bars include ^3-^2 figures. It might therefore seem reasonable to call it an "interpolation of multiple elements" if not for the fact that Chris Martin of Coldplay is featured on this track. It seems likely that Martin composed and performed both piano riffs. Assuming this is so, it is uncertain if Martin knowingly recycled another of his songs, or if it is simply a matter of different works by the same composer sounding similar due to reliance on the same set of tools and strategies.

Other Borrowing in the Music of Dua Lipa

Although not all entries on the music of Dua Lipa are straightforward examples of borrowing, they do provide a helpful overview of the ways in which her songwriting team uses pre-existing music as a starting point for creating a new song. The three reported interpolations discussed above revealed the following practices: 1) paraphrasing a well-known text 2) adopting common disco elements, and 3) re-using a familiar chord progression, transposed up by a step. It so happens that "Don't Start Now," one of Lipa's biggest hits to date (reaching #2 on the UK Singles and US Billboard Hot 100 alike) shows evidence of all three strategies when compared to its apparent model: Gloria Gaynor's "I Will Survive." Both songs are minor mode, mid-tempo disco tunes featuring "jumpy," off-beat (dotted-eighth) clean guitar hits during the verses and violin-led interludes; the lyrics of each present defiant rejection of the advances of a former lover 18 in an intimate, second person address. 19 Beyond these general stylistic similarities, certain passages in "Don't Start Now" are clearly adapted from "I Will Survive." 20 See in Figure 19 that the opening lyrics of Lipa's second verse are paraphrased from Gaynor's. The post-chorus (or "dance chorus") of "Don't Start Now" likewise alludes to "I Will Survive;" see in Figure 20 that both songs feature analogous passages of snappy utterances in a narrow melodic range with lyrics on a similar theme.

Comparing the chord progression in each song is also revealing. "I Will Survive" features a descending fifths sequence throughout, forming a complete diatonic circle of fifths; most sections of "Don't Start Now," rather, are built upon an ascending fifths sequence. "Don't Start Now" therefore has the same chord progression as "I Will Survive," but backwards (see Figure 21). 21 This observation is intriguing when one considers the first words the of the opening verse: "Did a full 180." 22 Whether or not the writers of this song noticed this theme of reversal, this is an appealing thread to follow on the aesthesic (interpretive) level. Most striking in this regard is the seemingly minor difference in lyrics in the lines shown in Figure 19 above, in which Lipa replaces Gaynor's "one" with the word "guy." Perhaps the reason for this change is simply to continue the rhyme scheme established in the opening verse; compare the di-syllabic rhyme (emphasized by the falling melodic contour) in both verses of "Don't Start Now" in Figure 22. 23 Nevertheless, this subtle textual shift changes the tone of the song profoundly. Gaynor's rhetorical question assigns no gender to the former lover. In fact, the entire song avoids the use of gendered pronouns (addressing an ambiguous "you" for most of the song) vowing to seek out "someone" who will reciprocate her love. Though Lipa retains this genderless address in the chorus ("If you don't wanna see me dancing with somebody"), the mention of a male lover elsewhere in the song erases the queer coding—that is, "does a full 180" in messaging—and, unlike "I Will Survive," it offers no disruption to pop's privileged space of white heteronormativity. 24

CASE 4: CLASSICAL MUSIC

Although whosampled.com was designed for documenting samples, covers, and remixes in popular music, information about borrowing in wide range of genres can be found on the site, including Western Art music. Some of the information about classical music on whosampled.com may seem peculiar to specialists, as fewer users of the site are accustomed to the conventions of the genre. Arrangements of classical works for new instruments or ensembles are often classified as "cover" versions. 25 If a song contains a quotation of an orchestral piece, it is usually categorized as a sample of either a "hook/riff" or "multiple elements." (Users of the site seem to be split on which category is most intuitive, as can be seen in the Appendix tables below.) Once one grows accustomed to the quirks of this organizational system, however, most users should find whosampled.com to be an invaluable resource for finding examples in which classical sources are adapted for use in popular song. See Appendix C for three clear examples of (respectively) so-called "covers," remixes, and samples of Western Art music in other genres.

In addition to the thousands of examples of borrowing from Classical music in pop songs, borrowing practices in Western Art music are documented on the site as well. I studied every reported example (about 200 in total) of "sampling" in music with the genre label of "Classical." As manipulation of recordings has only been practiced for a few decades, most "Classical" examples are, unsurprisingly, classified as interpolations rather than direct samples. 26 See Appendix D for examples of contained, referential quotations in which a composer borrows a fragment of another piece, Appendix E for adaptations of religious or vernacular tunes as a significant theme in a concert work, and Appendix F for a miscellany of other forms of intertextuality, including uses of national anthems and other commonly borrowed tunes, self-quotation, and variations upon existing themes. Unless otherwise specified, the examples provided on these tables are didactically clear examples of the types of borrowing listed.

Unfortunately, there are occasional obstacles to accessing the information about Western Art music on whosampled.com. For one, searching for all "samples" by the same composer is not always a straightforward process. Sometimes there are multiple "artist" entries for a single composer ("Schoenberg" and "Arnold Schoenberg" are, frustratingly, listed separately); in other cases, a performer, conductor, or ensemble is the listed artist rather than the composer. Another issue is the lack of appropriate categories for describing borrowing practices in classical idioms; this requires one to listen to the recordings comparatively to understand the nature of the similarity between them. A case in point, the following recordings are all classified as "covers" of the Prelude from Bach's first Cello suite (BWV 1007): Jan Vogler's earnest performance of this piece for cello, two different arrangements for solo guitar, and an electronic/dance version with a club-ready beat. While using the term "cover" to describe a wholly "normative" recording of a Classical piece—a work from a musical tradition in which there is no definitive recording to define the work concept—is conceptually fraught, the analogy of likening novel versions of familiar pieces to popular music covers is fair and intuitive. Such complications make for some noise to sort through, yet this is no reason to dismiss the troves of information about borrowing in Western Art music available at one's fingertips on whosampled.com.

CONCLUSIONS

From studying hundreds of reported samples on whosampled.com in detail, several conclusions can be drawn about the usability of this website. First, not only for the music of Bruno Mars, Janelle Monáe, Dua Lipa, but throughout the examples on whosampled.com, the reported "direct samples" are generally more accurate than are the interpolations. Whether or not every example listed is a true digital sample (many are actually re-recorded but classified as "direct"), the sources are usually identified correctly. The reported interpolations, though generally still illustrative of musical similarity between two works, are more likely to be unclear or misleading when identifying apparent borrowing. Consequently, Appendix A, which provides clear examples of each type of direct sample, was far easier to create than was the chart of accurate interpolations in Appendix B. Direct samples of drums, for example, are commonplace, and easy to evaluate. Truly convincing interpolations of drumbeats are rare; a beat must be truly distinctive for it to be heard as a case of one drummer "quoting" the work of another.

Second, the more distinctive the passage is, the greater the likelihood that an interpolation will be identified correctly and uncontroversially. Reported "samples" of common, "factory issue" progressions are less likely to have a single, identifiable source (as seen with the possible borrowing from Shai's "Baby I'm Yours" in Bruno Mars's "Straight Up and Down"). Pentatonic passages are similarly challenging. In a scale with fewer notes available, there are fewer distinctive scale-wise melodic patterns, and claims that one similar-but-not-identical pentatonic melody is based upon another are difficult to evaluate (as seen with Monáe's reported quotation of the Sesame Street counting song). Several whosampled.com users, for example, have identified echoes of other pieces in the relentlessly pentatonic melodies or stock drumbeats of The Black Keys; most of these entries do sound like their reported sources—often strikingly so—but few feature material distinctive enough that they can confidently be classified as quotations without qualification (Table 7). 27

| Black Keys Song | Material Borrowed | Reported Source |

|---|---|---|

| "Heavy Soul" (2002) | Multiple Elements | T-Model Ford, "Here Comes Papa" (1998) |

| "Busted" (2002) | Hook/Riff* *Classified as direct on the site; if it is indeed a quotation, it is re-recorded. | R.L. Burnside, "Skinny Woman" (1997) |

| "Stack Shot Billy" (2004) | Vocals/Lyrics | Vera Hall, "Trouble So Hard" (1960) |

| "She's Long Gone" (2010) | Hook/Riff | Muddy Waters, "She's Alright" (1968) |

| "Everlasting Light" (2010) | Multiple Elements | T. Rex, "Mambo Sun" (1971) |

| "Gold on the Ceiling" (2011) | Hook/Riff | Gary Glitter, "Rock and Roll Part 2" (1972) - aka the "Hey Song." |

| "Waiting on Words" (2014) | Hook/Riff | Kool & the Gang, "You Don't Have to Change" (1974) |

Third, the style or genre of music discussed correlates closely to reliability of information provided on the site. As the practice of sampling is most closely associated with hip hop and R&B, whosampled.com is set up to discuss music in these genres specifically; there are categories for samples of Drums, Vocals, and Bass—but not any other instruments—because these three layers are the most likely to be sampled in (especially) hip hop. The category "hook/riff" is left as a single catch-all category for music produced by a guitar, keyboard, saxophone, or just about any other imaginable instrument, which makes for an unfortunate lack of precision documenting borrowing in (respectively) rock, pop, and jazz. The farther afield one ventures stylistically from hip hop/R&B, the less likely the entries are to be accurate. Despite the many clear examples of borrowing in and out of Western Art music on whosampled.com, shown in Appendices D, E, and F, most of these examples are drawn from music since the mid-nineteenth century. Few users of the site have a deep enough knowledge of music the Baroque Era and before to distinguish quotations from works in a similar style. Does Handel, for example, truly borrow from Muffat and Stradella, as one whosampled.com user claims (Table 8), or are some of these cases simply the use of the same schemata in two otherwise unrelated works? 28

| Reported Source | Material Interpolated | Work by Handel |

|---|---|---|

| Alessandro Stradella, "Qual Prodigio è Ch'io Miri," (1681 Trio Sonata) | Mult. Elements | "He Spake the Word," Israel in Egypt (1739) |

| Mult. Elements | "He Gave them Hailstones," Israel in Egypt (1739) | |

| Gottlieb Muffat, "Fantasie" | Hook/Riff | Sampson, Overture |

| Hook/Riff | "From Harmony, From Heavenly Harmony," Ode to St. Cecilia's Day |

For all its idiosyncrasies, whosampled.com is nevertheless an invaluable resource for DJs, producers, and scholars alike. As demonstrated in the above four case studies, many reported "samples" are clear instances of one piece borrowing directly from another; others are instead identifications of passing resemblance, stylistic allusion, or adaptation (broadly defined). Yet even the entries that do not convincingly identify a single prior source of a passage are still informative; whether or not they present clear evidence of borrowing, such examples raise broad, ever-present questions about similarity, intertextuality, and the creative process in music writ large.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks are due to Trevor DeClercq and Deborah Wagnon for reviewing and responding to my work, and to the staff of Empirical Musicology Review for facilitating the review and editorial process, including Annaliese Micallef Grimaud (copyeditor), Jonathan Tang (layout editor), and Dan Shanahan (general editor).

NOTES

-

Correspondence can be addressed to: Jeremy Orosz, Ph.D, Associate Professor of Music Theory, University of Memphis, jorosz@memphis.edu. University of Memphis, Rudi E Scheidt School of Music, 3800 Central Ave, 38152, Memphis TN, USA

Return to Text -

See Orosz (2015).

Return to Text -

This calls to mind the questions raised in Burkholder (2018) about whether there is sufficient evidence to suggest that one composer has borrowed from another.

Return to Text -

Less common categories include samples of "Soundtrack" and "Dialogue." These categories are rare in part because of their redundancy; the former is a subcategory of "Hook/Riff" or "Multiple Elements" while the latter can usually be classified as "Vocals/Lyrics."

Return to Text -

The "orchestra hit" sound originates from a sample of a full orchestral texture in Stravinsky's Firebird. See Fink (2005), as well this helpful Vox video, which provides a remarkably comprehensive history of this sound: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8A1Aj1_EF9Y.

Return to Text -

Other references to "All Gold Everything" can be found in both the lyrics and rhythm of the vocals of "Uptown Funk." As a user on whosampled.com makes clear, the verse that includes the lyrics "this one's for them hood girls, them good girls, straight masterpieces" is a paraphrased from the Trinidad Jame$ (with a few of the nouns replaced).

Return to Text -

See Sisario (2023) for a summary of this trial and its verdict.

Return to Text -

An instructive example is a 2017 Saturday Night Live original number "Come Back Barack" (featuring Chance the Rapper); the writers of this send up of 90s R&B crooner simply could not help but give Keenan Thompson the opportunity to attempt such a husky-voiced spoken address.

Return to Text -

Though I do not presume my listening experience to be universal, neither do I imagine that it is so wildly idiosyncratic that I am alone in this perception.

Return to Text -

See Spicer (2010) for discussion of style in the music of The Police.

Return to Text -

I played this single bar of "Locked Inside" for the students in my class in March of 2021. Two out of the eight students present said that this reminded them of Michael Jackson's "Rock With You."

Return to Text -

The concepts of "signifyin(g)" in Afro-American literature is proposed in Gates (1988). Though Gates only provides a single example of musical signifying—Jelly Roll Morton's version of Joplin's "Maple Leaf Rag"—many scholars of Afro-American music have further developed musical applications of this concept. See especially Brackett (1995).

Return to Text -

The music video for Aerosmith's "Pink" was in regular rotation on MTV in 1997, around the time of Monáe's twelfth birthday. If her/their pop-cultural consumption was like that of a typical teenager, it is likely that she/they would have become familiar with "Pink" while it was a hit.

Return to Text -

To be precise, "Nasty Girl" is a ¼ tone lower than "I Got the Juice." The two songs may—or may not —have been conceived in the same key but the former falls outside of standard tuning.

Return to Text -

In an article for NME, Daly shows a now deleted Facebook post from an associate of Prince (a DJ), who claimed that Prince wrote the song and gave it to Monáe. Though plausible—if far-fetched—there is, to my knowledge, no evidence to confirm or refute this claim.

Return to Text -

Especially remarkable is that fact that no reported samples from Dua Lipa's "Levitating" appear on whosampled.com, given the fact Lipa and her team faced two copyright infringement lawsuits over this song in March of 2022. See Orosz (2022) for the details of these cases.

Return to Text -

Lipa's "Genesis" begins with the following words: "In the beginning God created Heaven and Earth. For what it's worth, I think that he might've created you first. Just my opinion."

Return to Text -

Despite their shared theme of heartbreak, the message of the two songs is remarkably different, while "I Will Survive" is about gaining strength in healing from the trauma of an abusive relationship, "Don't Start Now" is about going to the club to blow off steam to escape a suddenly "clingy" former beau.

Return to Text -

See Burns (2010) for discussion of second-person address and its significance in the work of female songwriters.

Return to Text -

If the referent were not already clear from this excerpt, the subsequent line of "Don't Start Now" includes the word "survive" (shown in Figure 22), all but abandoning plausible deniability that Lipa's team found inspiration in Gaynor's track.

Return to Text -

Note that although "I Will Survive" is a rare example of a pop song that is truly in a minor key, the chords are presented here in the relative major for the sake of clear comparison to "Don't Start Now."

Return to Text -

In some versions of the song, the opening lyrics of the first verse are the first words heard, as in the NPR tiny desk concert of December 2020. The studio version, however, features a "down" (quiet) half-chorus as an introduction before the first verse, in which a digitally processed shadow of Lipa's willowy head voice is heard at low volume. Regardless of the version, "Did a full 180" are first words both sung in full voice and placed prominently in the mix.

Return to Text -

This emphasis on rhyming syllables through descending step motion is reminiscent of Paul McCartney's "Yesterday… far away… here to stay" pattern in the Beatles' oft-covered classic.

Return to Text -

Also see Hubbs (2007) for discussion of the queer following of both disco more generally, and the significance of "I Will Survive" to the LGBTQ+ community specifically.

Return to Text -

See Gracyk (2012/2013) for a thoughtful exploration of how the term cover is used—often problematically and misleadingly—even within popular music practice.

Return to Text -

At the time of writing, two direct samples are listed in the music of Terry Reilly, and about two dozen in the music of John Zorn.

Return to Text -

This table includes all reported interpolations in the solo work of the Black Keys, and one interpolation that is falsely classified as a "direct" sample. Excluded are 1) clear direct samples in the Black Keys' music (of which there is only one on the site) and 2) several clear "interpolations of vocals/lyrics" in their collaborations with rappers, in which their guest artists clearly paraphrase rapped vocals from pre-existing songs.

Return to Text -

Consider also that the same user suggests that the introduction of "Because" by the Beatles is an interpolation of Beethoven's "Moonlight" Sonata. Both feature the slow arpeggiation of a minor triad; beyond that, it is dubious to call one a "sample" of the other.

Return to Text

REFERENCES

- Brackett, D. (1995). Interpreting Popular Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Burkholder, J.P. (2018). Musical Borrowing or Curious Coincidence?: Testing the Evidence. Journal of Musicology 35(2), 223-266. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2018.35.2.223

- Burns, L. (2010). Vocal Authority and Listener Engagement: Musical and Narrative Expressive Strategies in Alternative Female Rock Artists (1993–95). In M. Spicer & J. Covach (Eds.), Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music (pp. 124-153). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Daly, R. (2018). There's a very good reason why Monae's huge new single sounds like Prince. NME, Feb 26, 2018.

- Fink, R. (2005). The Story of ORCH5, or, the Classical Ghost in the Hip-Hop Machine, Popular Music 24(3), 339-356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143005000553

- Gates, H. L. (1988). The Signifying Monkey. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gracyk, T. (2012/2013). Covers and Communicative Intentions, Journal of Music and Meaning 11.

- Hubbs, N. (2007). "I Will Survive": Musical Mappings of Queer Social Space in a Disco Anthem. Popular Music 26(2), 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143007001250

- Orosz, J. (2015). John Williams: Paraphraser or Plagiarist? Journal of Musicological Research 34(4), 299-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411896.2015.1082064

- Orosz, J. (2022). Dua Lipa's "Levitating" Plagiarism Lawsuit Could Change Music Forever, Slate (March 17, 2022).

- Sisario, B. (2023). Ed Sheeran Wins Copyright Case Over Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On", New York Times (May 4, 2023)

- Spicer, M. (2010). "Regatta de Blanc": Analyzing Style in the Music of the Police. In M. Spicer & J. Covach (Eds.), Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music (pp. 124-153). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

APPENDIX

| Direct Sample of Drums |

|---|

|

Percussive sounds are copied into a new recording, including sound produced by acoustic percussion instruments (most often a drum set), electronic/synthesized percussion, hand claps, finger snaps, etc. Examples:

|

| Direct Sample of Bass |

|

The sound of a bass guitar, acoustic (stand-up) bass, or synthesizer (in low register) is copied into a new recording. Funk and soul records from the "long" 1970s are the most common records from which basslines are sampled. Examples:

|

| Direct Sample of Vocals/Lyrics |

|

The sound of a voice or voices (speaking, singing, or rapping) is copied into a new recording. Examples:

|

| Direct Sample of Hook/Riff |

|

A single instrument part (piano, guitar, etc.) or layer (string section, horn section) is copied into a new recording. Bass and Drums are typically excluded from "hook/riff," as each has its own category. Examples:

|

| Direct Sample of Multiple Elements |

|

More than one of the above layers is copied into a new recording. May include both vocal and instrumental parts, or at least two instrumental layers. Examples:

|

| Direct Sample of Sound Effects/Other |

|

Any material that cannot easily be classified in any of the above categories is copied into a new recording, most often a "sound effect" or sonic biproduct, such as speaker feedback. Examples:

|

| Interpolation of Drums |

|---|

|

A memorable rhythmic pattern of percussive sounds is quoted and re-recorded by a new performer or performers(s). This is a relatively rare category, as the quoted "beat" must be distinctive enough to be recognized without any other instruments or layers. Examples:

|

| Interpolation of Bass |

|

A performer re-records a bass line for use in a new song. The borrowed bass line typically features prominently in the original context from which it is borrowed. Examples:

|

| Interpolation of Vocals/Lyrics |

|

A vocal melody and/or lyrics are borrowed in and performed vocally. Both lyrics and melody may be borrowed together, or one may be borrowed without the other. Examples:

|

| Interpolation of Hook/Riff |

|

A short segment performed on one or more instruments or voices (typically excluding bass and drums) is quoted and performed by an instrumentalist in the context of a new song. Examples:

|

| Interpolation of Multiple Elements |

|

A quotation of multiple parts borrowed and re-recorded into a new song. May include both vocal and instrumental parts, or at least two instrumental layers (typically drums and pitched instruments). Examples:

|

| Interpolation of Sound Effects/Other |

|

A sound effect is re-recorded and understood as borrowed material. Examples: No convincing examples on whosampled.com. This category is likely hypothetical. |

| Concert Works Sampled and Looped in Hip Hop/Rap Songs |

|---|

|

| "Updated" Concert Works with an Added Drumbeat |

(Note: These versions are most analogous to dance remixes of popular songs, but they are classified as "covers" on whosampled.com)

|

| Stylistically Contrastive "Covers" of Concert Works |

|

| Source(s) | Material Borrowed | Classical Piece containing quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Shostakovich Symphony 7, I | Hook/Riff | Bartok, Concerto for Orchestra, IV (mm. 76-84) |

| Wagner, Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (opening) | Hook/Riff | Berg, Lyric Suite (Largo Desolato); Debussy, "Gollywog's Cakewalk" (from Children's Corner) |

| Arthur Collins, "Hello My Baby" | Multiple Elements (Incorrectly listed as "Direct sample") | Ives, "Central Park After Dark" |

Several sources attributed, including:

| Hook/Riff | Saint-Saens, "Fossiles" from Carnival of the Animals |

| "Ach du Lieber Augustin" (Traditional) | Hook/Riff | Schoenberg, Second String Quartet |

| Rossini, William Tell Overture | Hook/Riff | Shostakovich, Symphony no 15 |

| Folk or Religious Source | Material "Interpolated" | Concert Work That Adapts a Vernacular Tune |

|---|---|---|

| "La Marche des Rois" | Mult. Elements |

|

| "Bonaparte's Retreat" | Mult. Elements |

|

| "Kamarinskaya"(Russian trad.) | Mult. Elements |

|

| "Ein Feste Burg" (Martin Luther) | Hook/Riff |

|

| "Frere Jacques" | Hook/Riff |

|

| "Veni Veni Emmanuel" | Mult. Elements |

|

| "At the Gate, at my gate" (Russian trad.) | Mult. Elements |

|

| "O Lord Save thy People" | Hook/Riff Mult. Elements |

|

| "Cadet Rouselle" | Mult. Elements |

|

| "Sunce jarko ne silas Jednako" | Hook/Riff |

|

| "Seventeen Come Sunday" | Mult. Elements |

|

| Type of Borrowing | Examples Documented on whosampled.com | |

|---|---|---|

| Quotations of the Dies Irae |

| |

| Quotations and Settings of National Anthems | "La Marseillaise" (French) |

|

| "God Save the Tzar" (Imperial Russian) |

| |

| Both French and Russian |

| |

| Self-Borrowing |

| |

| Selected* Uses of La Folia *The first six chronologically out of more than 20 examples are listed here. |

| |

| Uses of "La Mantovana" Theme (Cenci, 1600) |

Clear Cases

| |

| Variations and/or New "Twists" on a theme by another composer |

| |