THE identification and appreciation of text painting is dependent to a large extent upon the listener. To give a modern analogy, Charles Ives often includes quotations of other music in his works. Listeners familiar with the source tunes will have a very different listening experience than those unfamiliar with them. Studying height-related imagery and how it relates to pitch height is a good starting point for empirical studies of text painting, since the relation between the two has a more universal context, so is less culturally biased and easier to model numerically.

The target paper (Strykowski, 2016) is a worthwhile undertaking to quantify such illusory features in music. Deriving definitions and refining them by testing their effectiveness can allow for a more in-depth computational analysis of music, which can in turn reveal large-scale patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Future work could examine other musical features such as meter and harmony that may be useful for the implementation of computational rules. For example, harmonic text painting in Cipriano de Rore's O sonno, where the opening verse of the poem is set to music that contains nearly no non-harmonic tones until the last few words of the verse: "aspra e noiosa" ("harsh and humdrum") occur at a suspension and cadence. Also the "s" sounds in these words help to emphasize this harmonic painting.

Regarding composer intent, an interesting case of text painting can be studied in a composition currently being written by Stanford Computer Science professor Don Knuth for his 80th birthday. He is working on a composition for organ based on the Book of Revelation. He distills the text into 200 main concepts, and then uses the sequence of those concepts in the text to generate the form of the piece, verse by verse and chapter by chapter. See appendix A for his discussion of the compositional process from concept to motive, and for a performance of a sample draft of the composition.

One problem that Don encountered was the density of textual motives in the composition. With nearly 10,000 words in the Book of Revelation, significant distilling was necessary in order to limit the length of the composition to an hour. Likewise, in madrigals, not all height-imagery words are expected to correlate with pitch height. A composer will likely choose a subset to actively paint with, and perhaps painting a particular height word will suppress the possibility of painting a similar nearby word. A future study might investigate how these positional effects might affect word painting.

Another interesting follow-up study would be to examine a repertory which is known for a dearth of word-painting to see if the correlation of music to height-related imagery is lower than average. For example, one might expect motets to demonstrate a lower correlation between the music and height imagery in the text. Another interesting null-hypothesis study would be to examine how non-height imagery words are correlated to the definitions. I am preparing this online edition with Emiliano Ricciardi of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, based on his dissertation work (Ricciardi, 2015). The first phase of the project will be to publish a collection of around 600 madrigals by around 200 composers, which set around 200 of Tasso's poems to music. Several of the poems are set to music by over 20 different composers. These can serve as the basis for a complimentary study on word-painting across different composers, particularly in how they set the same word sequences to different music.

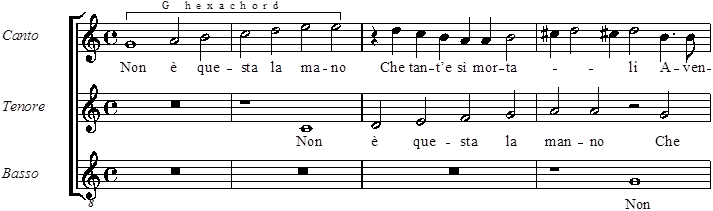

Appendix B lists 23 example musical settings of Tasso's Rime 47: Non è questa la mano ("Is this not the hand…?"). The setting by Ruggiero Giovanelli shown in Figure 1 demonstrates an example of word-painting with the opening motive in each voice spanning a hexachord in reference to the Guidonian hand. Human-identified word paintings such as this can also be used to search for other similar cases. For example, does this hexachordal pun occur in other cases where a hand is mentioned in the music?

REFERENCES

- Knuth, D. (2015). Constraint-Based Composition. Lecture given at Stanford University. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e_1a6bHGQGo

- Ricciardi, E. (2013) The musical reception of Torquato Tasso's Rime, 1571–1620. PhD dissertation. Stanford University,USA. Retrieved from https://purl.stanford.edu/ty888cc0725

- Strykowski, D. (2016) Text Painting or Coincidence? Treatment of Height-Related Imagery in the Madrigals of Luca Marenzio. Empirical Musicology Review 11(2) 109–119. https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v11i2.4903

Appendix

| Composer | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Pallavicino, B. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Quattro Voci. Venetia: Gardano, 1579 (RISM P0772) | |

| Marenzio, L. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Sei Voci. Venetia: Gardano, 1581 (RISM M500) | |

| Serafico, B. | Il Terzo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque et a Sei Voci. Vineggia: Herede di G. Scotto, 1581(RISM N0053) | |

| Cortellini, C. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Ferrara: Baldini, 1583(RISM C4173) | |

| Malvezzi, C. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Sei Voi. Vinegia: Herede di G. Scotto, 1584(RISM M0261) | |

| Mazza, F. | Il Secondo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Venetia: Vincenci e Amadino, 1584(RISM M1502) | |

| Scozzese, A. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Venetia: Vincenti et Amadino, 1584(RISM S2631) | |

| Gherardini, A. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Ferrara: Baldini, 1585(RISM 1585-24) | |

| Duc, F. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque et Sei Voci. Venetia: Vincenti et Amadino, 1586(RISM D3613) | |

| Sabino, I. | Il Quinto Libro de Madrigali a Cinque et Sei Voci. Venetia: Vincenti et Amadino, 1586(RISM S0050) | |

| Morari, A. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Quattro Voci. Venetia: Gardano, 1587(RISM M3615) | |

| Gastoldi, G. G. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Venetia: Amadino, 1588(RISM G0547) | |

| Giovannelli, R. | In Fiori Musicali, Libro Secondo. Venetia: Vincenzi, 1588(RISM 1588-20) | |

| Castro, J. de | Rose Fresche. Madrigali Novi a Tre Voci. Venetia: Amadino, 1591(RISM C1482) | |

| Monte, F. de | Il Sesto Libro de Madrigali a Sei Voci. Venetia: Gardano, 1591(RISM M3384) | |

| Ferro, P. M. | In Ferro, Giulio. Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Venetia: Amadino, 1594(RISM 1594-12) | |

| Gesualdo, C. | Il Secondo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Ferrara: Baldini, 1594 (G1725) | |

| Roccia, D. | Il Secondo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Napoli: Vitale, 1603(RISM R1807) | |

| Montella, G. D. | Primo Libro de Madrigali a Quattro Voci. Napoli: Sottile, 1604(RISM M3422) | |

| Ratti, L. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Cinque Voci. Venetia: Vincenti, 1615(RISM R0329) | |

| Cifra, A. | Madrigali Concertati a Cinque con il Basso Continuo. Roma: Soldi, 1621(RISM C2224) | |

| Capece, A. | Il Secondo Libro de Madrigali , et Arie a Una, Due, et Tre Voci. Opera Decimaquarta. Roma: Robletti, 1625(RISM C0898) | |

| Costa, G. M. | Il Primo Libro de Madrigali a Due, Tre, e Quattro Voci. Venetia: Vincenti, 1640(RISM C4221) |