THIS paper presents a semantic framework that organizes critical aspects of aesthetic experience for psychological and philosophical research. Recent years have seen a boom in attempts to draw together theories and empirical data on aesthetic experience (Jacobsen, 2006; Leder & Nadal, 2014) . Yet, as some accounts point out, there exist numerous gaps and confusions (e.g., Augustin, Wagemans, & Carbon, 2012; Konečni, 2012; Locher, Overbeeke, & Wensveen, 2010). One of the most critical is the definition of the aesthetic experience itself. An aesthetic experience may be defined through the philosophical concept of disinterested contemplation (Levinson, 1992). It may involve a combination of cognitive and emotional processes (Locher, et al., 2010). It may be defined in terms of the qualities of the object (music, artwork, etc.) or in terms of the affective sensations of the individual as a result of contemplating the object (Beardsley, 1969). The act of creative production (such as a musician playing at a concert, an artist painting in a studio, or a composer at work) and its relationship to the perception and contemplation of art works are involved (Tinio, 2013). The brain activity that corresponds to aesthetic experience is another way of defining the process, although the neuroscientific understanding of aesthetic experience is in its infancy (Brattico, Bogert, & Jacobsen, 2013; Brattico & Pearce, 2013; Calvo-Merino, Jola, Glaser, & Haggard, 2008; Cela-Conde, Agnati, Huston, Mora, & Nadal, 2011; Chatterjee, 2004; Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2014; Jacobs, Renken, & Cornelissen, 2012; Thakral, Moo, & Slotnick, 2012; Trost, Ethofer, Zentner, & Vuilleumier, 2012; Vartanian & Skov, 2014; Zatorre & Salimpoor, 2013). Other authors have argued that it can refer to pure pleasure, highly profound feelings, or the formation of meaning, interpretation and understanding (Armstrong & Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Bullot & Reber, 2013; Leder, Belke, Oeberst, & Augustin, 2004; Leder & Nadal, 2014). None of these perspectives on aesthetic experience are mutually exclusive (Pouivet, 2000).

The recent arrival of cognitive and neuroscientific perspectives into the debate about the definition of aesthetic experience has seen an important epistemological shift, now joining an area that has hitherto been largely the domain of philosophy. This has placed greater pressure on basic matters of terminology, because while philosophers contest questions such as 'what is an aesthetic experience' (e.g. Beardsley, 1969; Dickie, 1997; Ingarden, 1961; Shusterman, 1997), psychologists often draw attention to the emotional aspects of such experiences and use terms interchangeably, and at times in a rather imprecise manner, but with the primary aim of reduction and measurement (Perlovsky, 2014a, 2014b).

We see the role of emotion as jostling for intellectual consideration with the more traditional definitions that are concerned with beauty and the sublime. For example, Brattico, Bogert, & Jacobsen (2013) argue that "the aesthetic experience comes to full fruition by inducing emotions in the individual (particularly aesthetic ones…), by prompting an evaluative judgment of e.g., beauty, and by determining liking and a time-lasting preference" (p. 2, column 2). The question we seek to answer is whether all of these components (evaluative judgment, emotion, and preference) are necessary and sufficient to achieve this fruition. Preference alone clearly cannot be such because we are able to have preferences for non-aesthetic objects, activities and situations (eating, swimming, and so on). In this paper we take a linguistic perspective to addressing the question, since the key problem at hand is one of definition of terms and structure of meaning.

We will argue that one way in which the variety of terms used to describe and understand aesthetic experience can be brought under closer scrutiny and analysed with greater consistency is to present a semantic framework within which distinct and related concepts can be organized. Driven in particular by recent neuroaesthetic accounts, such as those of Brattico and Pearce (Brattico & Pearce, 2013) and Brattico, Bogert, and Jacobsen (2013), as well as Juslin's (2013) work on emotion in music, we propose a semantic framework which future research may use to help organize concepts concerning aesthetic experience. Perhaps controversially and despite overlapping and inconsistent usage, we will argue that there is utility in semantically separating the terms emotion and affect in understanding the aesthetic experience more clearly. Although we make several references to literature concerned with aesthetics and emotion in music, the framework can be generalized to other objects (for examples of the kinds of objects that may be included, see, e.g. Augustin, et al., 2012).

The approach taken here is essentially reductionist and 'dimensional', meaning that a small number of core components are identified which are evidently contributors to the aesthetic experience. Such an understanding of experience has a long history, with numerous, related theories found in the psychological literature. Wundt (1897) proposed three dimensions ('directions') of 'affective quality and intensity' which were described as (1) pleasurable and unpleasurable, (2) arousing and subduing (exciting and depressing), and (3) related to feelings of strain and relaxation (p. 83). Nowadays (particularly the first two of) these are thought of as orthogonal dimensions of emotion, with the first dimension referred to in terms of pleasantness or valence, and the second in terms of arousal or activity (Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957; Plutchik, 1962; Russell, 1980; Schimmack, 1999; Schimmack & Grob, 2000; Schimmack & Rainer, 2002; Schlosberg, 1952, 1954). However, our approach does not focus on the structure of emotions per se, but rather the on aesthetic experience. These experiences may or may not involve emotion, as we shall explain.

Specifically, we present a framework which organises 'affect' and 'emotion' as having separable and distinct experiential components. We begin by presenting two areas of aesthetic experience that are controversial and/or referred to in an inconsistent manner, but are nevertheless considered fundamental to the aesthetic 'experience', namely hedonic tone (Crisp, 2006) and aesthetic emotions (Perlovsky, 2014b). We then present our framework, through which we explain how the understanding of aesthetic experience can be organized in a systematic way (following from the suggestion proposed by Cochrane, 2010).

Hedonic Tone

During artistic contemplation (e.g., engaging with a work of art or a piece of music, whether as an observer/listener or performer/creator) a wide variety of attraction/repulsion experiences can be encapsulated, from 'shallow', simple like-dislike responses, often referred to as preference, through to aesthetic-pleasure, which for some is similar to liking, but for others refers to experiences beyond the mundane. These special episodes are 'deep' experiences and may involve feelings such as frisson, awe and spirituality (Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Konečni, 2005; Maslow, 1954), flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991) or being moved (Hanich, Wagner, Shah, Jacobsen, & Menninghaus, 2014; Kuehnast, Wagner, Wassiliwizky, Jacobsen, & Menninghaus, 2014). The use of the term 'deep' seems appropriate because it corresponds to the activation of the upper echelon of Maslow's hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1948) and refers to profound experiences tending towards 'self-actualisation' (reaching or approaching one's full potential as a human being) which are differentiated from more mundane, 'shallow' levels of attraction, such as liking and preference. 2

For many writers, at least since Burke (1806/1757), the deepest level of hedonic tone is sublimeness (Cochrane, 2012), although, as we will see in the discussion of locus, 'sublime' is a term better reserved to describe the perceived object, or to describe a bridge between the perceived object and the affective experience (Beardsley, 1969). Konečni (2005) organizes his own hierarchy of aesthetic experience around the level of profundity, with 'aesthetic awe' at the highest of three levels, and occurring most rarely, with 'thrills' being more common and less profound, and with 'being moved' in between (see also Hanich, et al., 2014): together, the three experiences are seen as forming an 'aesthetic trinity'.

While few studies address the 'hierarchy' of these different levels of experiential depth in response to art works in any detail, it is critical to provide some way of organizing them. Particularly confusing is whether the wide range of hedonic tones is part of the same subjective construct, ranging from shallow (e.g., liking) through to deep (e.g., awe), or whether there are categorical, subjectively-discernible differences at different points, for example where awe is seen as a completely different (independent) dimension of experience as compared with liking (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). For example, what we suggest is part of a deep level of hedonic tone is considered by some to be a special set of 'aesthetic emotions', which are distinct from day-to-day liking and preference. The definition of aesthetic emotions is another controversial area, but one which has received considerably more attention in the literature than the question of the depth-hierarchy conceptualization of hedonic tone. We turn our attention to this definition.

Aesthetic Emotions

Aesthetic emotions are a special set of emotions that are activated usually when contemplating a work of art. They provide a phenomenological realisation of disinterested attention, the state that, according to Kant (1952/1790) and his followers, one must be in when contemplating a work of art. That is, when one is engaging with a work of art, or more specifically with its beauty, but without desire (without the desire to acquire it, and without worrying about everyday life distractions, such as paying an outstanding bill, and so on), one experiences pleasure, or some might say 'aesthetic pleasure' (see also Perlovsky, 2014a; Perlovsky, 2014b). Aesthetic emotions provide a language through which to communicate the experiential aspects of this pleasure. The concept of aesthetic emotion is therefore potentially useful and could benefit from specific criteria regarding its nature and its relationship with other aspects of emotions, affects and experiences.

As we have seen from Konečni's perspective, aesthetic emotions occur in successful artistic contemplation, and for Scherer and colleagues, are distinguished from everyday utilitarian emotions (Scherer, 2004, 2005; Scherer & Zentner, 2001; Zentner, Grandjean, & Scherer, 2008). For others aesthetic emotions are the same as those employed in non-aesthetic experiences, although they may occur more frequently when engaging with the arts than they do in everyday life (e.g. Juslin, 2013; Perlovsky, 2002). These varied perspectives have their roots in philosophy as well as the definition and nature of aesthetic emotions (see further, Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Perlovsky, 2014a, 2014b; Pouivet, 2000) which has motivated researchers in psychology to aim for a high level of precision when dealing with the nebulous concepts that the study of emotion demands.

Thus, one of the purposes of the concept of the aesthetic emotion is to reconcile the traditional view of beauty in the aesthetic experience. From a research perspective, the 'aesthetic emotion' concept shifts the focus of aesthetic experience away from the perception of the object (which we refer to as residing in the 'external locus') and into the highly personal, subjective realm of experience (residing in the 'internal locus'). This situation is more complex than the present discussion allows, but some scholars have even suggested an equivalence between beauty, pleasure, and aesthetic emotion (see Armstrong & Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Langer, 1957, p. 259; Martin, 1956, esp. fn 13) which in our reading has been left unresolved.

The term aesthetic emotion therefore has different meanings for different people. For many, 'aesthetic awe', albeit in a somewhat circular manner, is uncontroversially an aesthetic emotion, whereas for others, terms such as preference and pleasure are included (e.g. Hargreaves, 1986, pp. 107-108). The problems leading to this confusion and controversy about aesthetic emotion include determining specifically what constitutes such an emotion and how the various terms can be distinguished semantically.

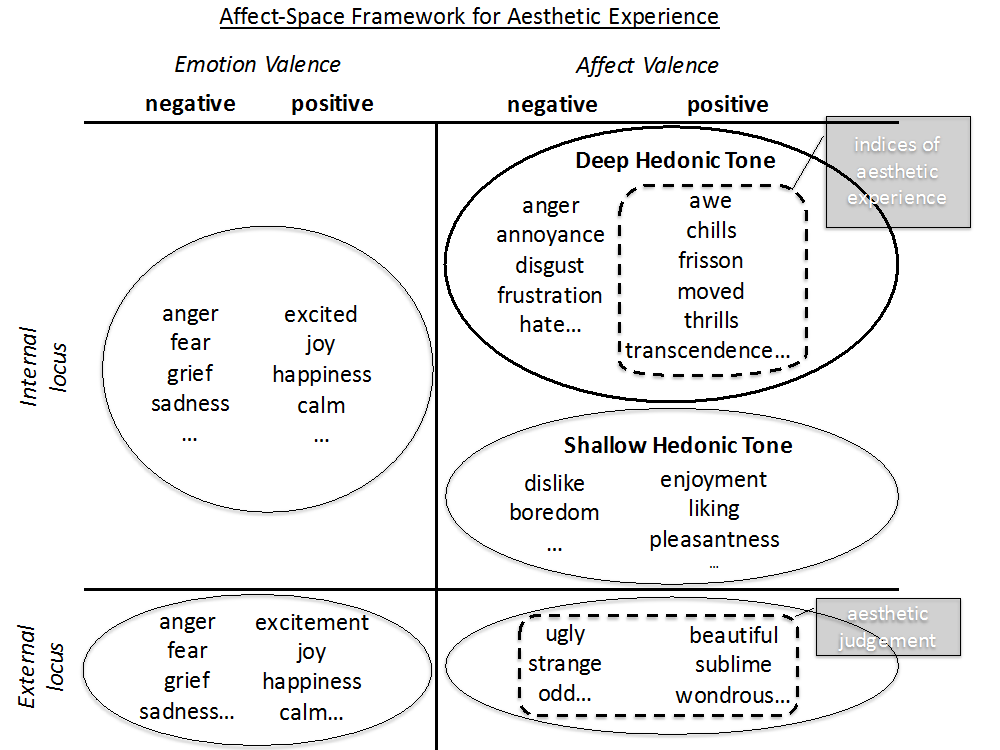

In addition to the question of hedonic tone and aesthetic emotions, we therefore focus on the semantics of emotion as they relate to aesthetic experience. In particular, we tease apart how 'emotion' and 'affect' are terms that are often used interchangeably (Juslin & Sloboda, 2010), but might be better thought of as two different entities. Our approach consists of three classifications, which we describe in the following section and will expand and justify in the sections which follow. Specifically, we propose (1) to introduce a linguistic differentiation between 'emotion' and 'affect', inspired by the work of Charland (2005) and Colombetti (2005), (2) to expand the conceptualization of locus (internally generated feeling versus perception of an object), and (3) to present a conceptualization of hedonic tone based on the 'depth' of the experience as already discussed. From these proposals we will develop an affect-space framework, which is illustrated in Figure 1, to demonstrate how we differentiate and organise emotions, affects, and, consequently, aesthetic experiences.

Three Classifications

Affect-Valence and Emotion-Valence

Emotion is a highly complex phenomenon that psychologists frequently reduce to a small number of underlying components or items for ease of analysis, and to better understand its structure. As we mentioned earlier, the dimensions of valence and arousal are both relatively common manifestations of the underlying theoretical structure of emotions. But even the single dimension of valence has generated a heterogeneous body of literature in philosophy and psychology (for a review, see Colombetti, 2005). To give just four examples out of several, questions arise regarding (1) the nature of the pleasantness ( - unpleasantness) of an emotion, (2) whether this pleasantness ( - unpleasantness) is a separable add-on or whether it is integral to some or all emotions, (3) whether the pleasantness ( - unpleasantness) can be equated with approach - avoidance (attack - withdrawal) motivation, and (4) whether the emotion feels good ( - bad).

While both Colombetti (2005) and Charland (2005) are cautious in giving a definitive solution, one way in which they both proposed that 'emotion' can be conceptualized draws on the distinction between affect-valence and emotion-valence. Colombetti (2005) distinguished between the character of an emotion and the 'aspects' of an emotion, arguing that there are subtle but important distinctions between the two. The character can be thought of as a mental state and can be labeled emotion-valence. The aspects of an emotion can be thought of as the feelings that initiate or constitute an action, judgement, evaluation, desire and/or motivation, and can be labeled affect-valence. For example, if one experiences anger, there will be components of the anger concerned with a bodily condition and mental states (I feel angry/bad) without any obvious motivational content, but there will also be motivational components (some overlapping and some separable) concerned with action tendencies, such as attack, departing, or repulsion. In psychology these distinctions and the clusters within them are more easily thought of as a single, united emotion, or a (more or less) single location on a geometrically represented dimensional space. But some philosophers and psychologists are also interested in explaining what the various components might be, and how they fit together. In the psychological literature Scherer's (1984) component processes model of emotion has motivation-change as one of its components, which aligns with the concept of affect-valence (Schubert, 2016).

Schubert (2013b) applied these ideas to explain how it was that people could enjoy music that evoked negative emotion. In that study he argued that to better understand emotional and preference relationships with music, one must not only vary the kind of emotions evoked (as was typical in music psychology research on emotion), but also vary the preference level. He did this by asking each participant to select a piece of music that she/he loved and another that she/he hated, and the analysis of the self-reported responses of the participants revealed two different 'qualities' of emotions being reported. Approximately one third of participants spontaneously selected a loved piece of music that evoked negative emotions. As might be expected, for the hated piece, most participants reported negative emotions, but these emotions were qualitatively different to those emotions evoked by loved music. Loved music could evoke sadness and grief, while hated music evoked annoyance, boredom, frustration and disgust. While other emotions were also evoked in both conditions, it became evident that the differences in the qualities of the negative emotions needed to be explained.

In line with Colombetti and Charland, Schubert referred to the annoyance, boredom and anger evoked by the hated pieces as kinds of negative affect-valence, while the negative emotions evoked by the loved pieces, such as sadness were typically examples of (negative) emotion-valence, but because they were loved, their affect-valence was positive. The negative aspects of the hated piece experience were directly linked to the preparation for change in the inclination of the individual as driven by the hatred—such as the desire to avoid the music—and so were better conceptualized as describing affect-valence than emotion-valence. In other words, emotion-valence refers to the character of the emotion that someone is experiencing, whereas affect-valence refers to the (motivational) attraction to or repulsion from the object.

Hence a work of art can generate a feeling of happiness that invokes both affect-valence and emotion-valence. In the case of happiness, however, affect-valence and emotion-valence are difficult to separate experientially. One refers to the state of happiness, whilst the other is the desire to continue the activity or repeat it at another time.

As the above example demonstrates, in an aesthetic context, some negative valenced experiences are easier to separate. Frustration is generally an affect-valence when attempting to engage with a work of art, rather than a contemplative state. It drives the listener to act – to leave the place where the artwork is present, to switch it off, to attack it, to complain about it, and so on. Emotion-valence may be non-existent in this case, or completely blended with affect-valence. Feeling sadness, on the other hand, is more likely to involve emotion-valence responses when engaging with a work of art. The resultant affect-valence may be to be moved, thereby reflecting a motivation by, desire for, and/or attitude toward the work (liking or some other deeper level of hedonic tone). In this case, the two kinds of experiences are easier to distinguish because the emotion-valence (negative) is phenomenologically distinct and might even be in opposition to the affect-valence experience (positive).

In sum, affect-valence refers to the motivational aspect of an experience, while emotion-valence refers to the contemplative state of the individual. Emotion words can convey valence analogues of affect-valence and emotion-valence, such as happiness ('I like being happy'—the liking part is an affect-valence of happiness), but under certain circumstances, such as loving music that makes one feel sad, the loving is an affect-valence and the sadness is an emotion-valence. In that case, one happens to be positive (affect-valence) and the other negative (emotion-valence), although this need not always be the case.

Locus

Locus refers to the ontological source or 'ownership' of the phenomenon being described. One's own feeling is internal to oneself: 'I feel…', 'I am…', 'It makes me feel…' statements. On the other hand, explaining the emotions that a piece of music appears to be conveying means that the source of the emotion is external to the person doing the explaining. The distinction between internal and external emotion locus when listening to music has been well documented (Evans & Schubert, 2008; Gabrielsson, 2002; Schubert, 2007b, 2013a).

Aesthetic judgement has received less attention in psychology than in philosophy (Budd, 2008), although there are exceptions to this (see e.g. Augustin, et al., 2012; Tinio, 2013), and the term has been used by music psychologists (such as Brattico & Pearce, 2013; Juslin, 2013). Aesthetic judgements have an external locus because they apply to the object itself (for example, how beautiful or ugly it is). Aesthetic 'emotions', on the other hand, have an internal locus because they refer to felt affect (awe, frisson, etc.) in our framework. Extending the locus conceptualization from emotion into affect-valence helps to bring into focus the difference between so-called aesthetic 'emotions' and aesthetic judgements, as we will describe.

The emotion-valence/affect-valence distinction immediately resolves a number of matters that are currently controversial or anomalous. Generating so-called aesthetic emotions (internal locus) and aesthetic judgement (external locus) are the goals of artistic engagement. Pleasure, liking, awe, being moved, frisson and so on are examples of affect-valence and also involve internal locus (that is, they are 'felt' by the perceiver engaging with the object). These internal locus affects are the motivators that draw us to, and make us desire to maintain and to seek out, aesthetic experience. Importantly, these internal locus affects are the aesthetic experience in our framework, as shown the upper-right dotted region of Figure 1.3 That is, internal locus, affect-valence is a necessary condition for aesthetic experience.

Emotions, including sadness, grief, and also happiness, are mental landmarks, states, and/or contemplations which can contribute to the aesthetic experience. But they do not define aesthetic experience. Unlike the affect-valence examples mentioned, these are not necessary for an aesthetic experience to occur, and indeed one might be able to report an aesthetic experience without any emotion at all. This is a perspective taken by the so-called cognitivists such as Scruton (1983) and Kivy (1989), in the case of music engagement. They argue that the value of the artwork is in what it expresses, not what it evokes, a view that stems from the nineteenth century polemic of Hanslick (1854/1957).

Kivy's (1989) controversial position that "one substantial group of listeners who report that sad music makes them sad are simply (and understandably) mistaken" makes the point that whether one believes it is possible to experience negative emotions such as sadness in response to music or not, what is more important is that they feel excitement or awe or some other positive affect-valence, regardless of the emotion-valence reported. The aesthetic experience is an affect-valence, not an emotion-valence (if one should exist) and this distinction provides a clear basis for the aesthetic experience. It allows us to include emotion-like experiences that we argue are better thought of as affect-valence (including awe, being moved, frisson etc.), while allowing emotion-valence (happiness, sadness, grief etc.) to become transient aspects of aesthetic experiences without necessarily being integral components of them.

Depth

As already mentioned, deep level aesthetic experiences are those which are normally construed in the literature as pertaining to awe and being moved, but might also include feelings of transcendence, frisson, spirituality and so forth (Keltner & Haidt, 2003) – they are considered to be difficult to measure psychometrically and closer to the ineffable sensations involved when engaging with an object in an aesthetic context. In fact, it is this point that brings us to the critical aspect of our framework. According to Dickie's (1997) philosophical perspective, aesthetic experience should refer to the ineffable – to experiences that are aesthetic but cannot be put into words. Those seeking to understand aesthetic experience are thus driven to find surrogate language that can accurately convey the experience and hence, to date, terms like those listed in the deep hedonic tone (internal locus, affect-valence) region of our framework have emerged. But researchers in empirical aesthetics and, more recently, neuroaesthetics are now pursuing these terms, in a manner that is somewhat obstinate from the perspective of some linguistic and philosophical writers. Empirical psychologists are now directly testing terms such as 'beauty' and 'being moved', which should not be measurable (Dickie, 1997), and appropriating them for use in their research as dependent variables (e.g., Hanich, et al., 2014; Hekkert, Snelders, & Wieringen, 2003; Jacobs, et al., 2012; Kuehnast, et al., 2014). With each such additional term added to the scientist's psychometric tool kit we may be building a bigger picture of the nature of the aesthetic experience, but there are many obstacles to avoid in the process which are beyond our scope here (see further Berlyne, 1971, 1972; Dickie, 1997; Konečni, 2012; Naukkarinen, 2010).

The Affect-Space of Aesthetic Experience

To bring these matters together we present the affect-space framework shown in Figure 1. The figure shows emotion/affect-valence, locus, and depth level distinctions. The components are organized into a semantic space in which the term 'affect' is used in a broad sense, and is distinct from its more specific use in the term 'affect-valence' (Schubert, 2012). First we divide the semantic space into a two by two matrix, where the left column consists of emotion-valence, and the right column consists of affect-valence. Within each of these columns we list sample words (in regular text font) that exemplify negative (left subcolumn) and positive (right subcolumn) valence terms.

Fig. 1 Affect-space framework

The two rows of the matrix distinguish locus. The first row refers to felt experiences of the perceiver (internal locus), and the second row indicates qualities and character identified in, or expressed by the object/music/artwork that is being perceived (external locus). There is an asymmetry in the layout of the framework because while the emotion-valence column lists some identical emotion terms that can be both experienced (internal locus, first row) and perceived in the stimulus (external locus, second row), the second column does not share such symmetry. Here the organization is based on groupings that separate 'aesthetic emotion' and 'aesthetic judgment' terms. That is, we organize these terms as different kinds of affect-valence, with what is conventionally referred to as 'aesthetic emotions' being internal locus experiences with deep hedonic tone in the Affect-space framework, while aesthetic judgements include all possible judgments of an artwork/object. This can include both positive and negative valenced evaluations (beautiful, but also ugly), which allows for the incorporation of simultaneous, divergent views about what constitutes an aesthetic experience, such as the stereotypical derogatory descriptions one might expect for an avant-garde painting or a piece of pantonal music. Adorno (1997) points out that "the ugly must constitute, or be able to constitute, an element of art" (p. 63) and "the dialectic of the ugly has drawn the category of the beautiful into itself as well; kitsch is, in this regard, the beautiful as the ugly" (p. 66), giving one example of how Western art, particularly since modernism in the twentieth century, can allow such apparent contradictions to coexist. Because the terms suggested to describe or judge the work of art are distinct from those for internally generated feelings, we place them in the lower, external locus row of the matrix. The positive-negative valence division in both rows of the affect-valence column is retained.

A final division is made in the internal locus affect-valence cell, differentiating between the depth of hedonic tone of the experience. This distinction is necessary to highlight the possible limitations of using shallow hedonic tone terms to measure aesthetic experience. While the deep level terms are also limited because they may still be unable to label an experience that is ineffable, they are closer to the ideal aesthetic experience than the 'mundane', shallow terms. Above all, our model only requires the two dotted boxes of the affect-space to be activated for an aesthetic experience to occur: some index of the deep hedonic tone, and the possible presence of a causal object that induces a judgment about it (external locus affect-valence). Brattico and Pearce (2013), for example, require several components of their framework to be activated (usually), and, as mentioned, for Brattico, Bogert, and Jacobsen (2013) there are three outcomes of aesthetic experience: aesthetic emotions (which in our model correspond to deep hedonic toned, affect-valence, internal locus), judgement (affect-valence, external locus) and preference (shallow hedonic toned, affect-valence, internal locus).

In contrast to Brattico, Bogert, and Jacobsen's view, our framework highlights the need to further distinguish or clarify the role of 'emotion-valence'– whether this is considered to be inconsequential or interchangeable with 'affect-valence', or whether it is something that may require further attention. And again in contrast to these earlier frameworks, since shallow, internal locus affect-valence can be activated in so many (non-aesthetic) situations as well, the distinction between preference, liking and judgement does little to exclusively identify or define what is or is not aesthetic experience. But the framework does not need to exclude shallow hedonic tone from aesthetic experience. The question may be rephrased as: Where does deep hedonic tone experience begin and shallow hedonic tone experience end? In other words, how far should we extend or retract the dotted box shown in the internal locus, affect-valence quadrant of the affect space? For some researchers, such as those cited, the dotted box is defined by the deep-affect portion of the affect-space, but for others it might be the entire spectrum of affect-valence, encapsulating deep and shallow experiences (as discussed under 'Aesthetic emotions', above).

Implications and Further Applications

Emotion-valence, as we have argued, is not a necessary component of aesthetic experience, even though much empirical research focuses on emotion. The focus on emotion is an artifact of the confusion and melding of emotion-valence and affect-valence (Charland, 2005; Colombetti, 2005; Juslin & Sloboda, 2010; Schubert, 2012) and of the current fixation on emotion in aesthetic engagement, especially in music (Cohen, 2010). To remedy the confusion, we conceptualize aesthetic experience as being a subset of affect-valence—the dotted rectangle in the positive affect-valence region of Figure 1. The deep affect-valence that occurs as a result of contemplating/engaging with a stimulus that can have aesthetic judgement cast upon it (dotted rectangle on the bottom right cell of the matrix) is a necessary condition for aesthetic experience. But it cannot be sufficient because we concede, in line with Dickie (1997), that an aesthetic experience may be ineffable, and that the deep affect-valence terms offer the closest indices of the actual experience afforded to empirical aesthetics research using self-report methods. Although self-explanatory, the deep hedonic tone affect-valence becomes aesthetic when it is driven by the contemplation of external locus affect-valence generating objects or thoughts (Hargreaves, 2012), such as an object or piece of music judged to be beautiful or ugly. It is this context that changes its status from everyday, mundane, to aesthetic. The context changes from non-aesthetic to aesthetic, a view consistent with Juslin's perspective (esp. Juslin, 2013; Juslin, Liljeström, Västfjäll, & Lundqvist, 2010).

Shallow level affect-valence is historically closer to the psychometrically 'measurable' terms used in empirical aesthetics. That is, it provides a possible further index of an aesthetic experience, but researchers need to consider the benefits of the deep affect-valence terms to better capture the otherwise potentially ineffable aesthetic experience. However, the number of terms to describe a variety of deep hedonic tone experiences is large, and the nature of those experiences diverse, and so there is a chance that there will be aspects of experience missed by researchers. For example, while experiencing ineffable affect-affect as well as a sensation of awe, a participant is only asked to report how moved they felt: A major part of the aesthetic experience (the awe) was missed. Perhaps 'preference' rating is the safer, catch-all measure, even though an impoverished and shallow indicator of a possibly much richer experience.

The affect-space framework has implications for the mechanisms of emotional responses to music that have been proposed by Juslin (Juslin, 2013; Juslin, et al., 2010; Juslin & Västfjäll, 2008). Juslin has been understandably suspicious of the concept of aesthetic emotion, arguing that there is nothing particularly special about it because the emotions come from the same set that can be used in settings outside music, in everyday life (Juslin, et al., 2010). However, in one version of Juslin's account of the ways in which music arouses emotions, 'aesthetic judgement' is added as a new mechanism of emotional response to music (Juslin, 2013; Juslin, Harmat, & Eerola, 2014). Aesthetic judgement, for Juslin, makes his list of mechanisms an even more comprehensive explanation of the psychology of emotion in music. In this updated 'BRECVEMA' conceptualization, all of the emotion mechanisms proposed in earlier research are filtered through an aesthetic judgement ('A') function (or 'BRECVEM->A') which is able to generate outputs such as the music being beautiful, expressive, and so on. The similarity with our positive affect-valence idea is evident, but if we further distinguish Juslin's account according to locus in particular, but also affect-valence/emotion-valence and hedonic depth, the relationships between aesthetic judgement and aesthetic emotion may be further elaborated.

Aesthetic experiences are characterized by psychologists as consisting of internal-locus affect-valence terms that may or may not index ineffable feelings, such as awe and transcendence, but they also include phenomena such as preference, pleasure, and enjoyment (Brattico & Pearce, 2013), which are more shallow and perhaps easier to measure. The limitations of past psychological research based and 'actual' aesthetic experience can be more clearly brought to the fore using our framework.

Zentner, Grandjean, and Scherer's (2008) detailed study of the words used to describe emotion in music could also be further refined and applied to aesthetic experience research via the affect-space framework, because as it currently stands it mixes terms that might well be characterized as affect-valence terms (amazement, spirituality, power) and emotion-valence terms (joy, sadness). The nature of the affect-space framework can therefore inform debate about the linguistic and affective organization of aesthetic experience by elucidating that (1) the so called aesthetic emotions can be thought of as internal locus, deep-hedonic tone, affect-valence, and (2) affect-valence is conceptualized as something different to 'emotions' per se, but can occur simultaneously (in parallel) with emotions.

Brattico and Pearce (2013) raised the question of the relationship between pleasantness, preference and enjoyment, and considered it in terms of dimensional models of emotion. The dimensional approach presents a small number of axes that are indicative of broadly agreed labels along which all emotions can be mapped. Most common among these are two perpendicular axes, namely valence (labeled at the poles as positive and negative respectively) and arousal (labeled at the poles as high and low respectively), as discussed in the opening. Brattico and Pearce argued that the valence dimension is often treated as equivalent to pleasure. This equivalence raises the problem, for example, of how to conceptualize enjoyment (pleasure) when it is derived from experiencing negative emotions (negative valence)—such as when one enjoys a piece of music that makes one feel sad. One solution was suggested by Brattico and Pearce, namely to include an additional dimension labeled pleasure or enjoyment, to be used in addition to valence. In other words, they suggest a separation of what we refer to as emotion-valence and pleasure (which we argue is an affect-valence) to resolve the ambiguity that the two set of labels can cause. Valence as used in the two-dimensional valence-arousal emotion-space configuration (Russell, 1989; Schubert, 1999) refers essentially to emotion-valence while pleasantness is an affect-valence, referring, to pleasure and enjoyment. In our framework they are treated as different. We argue that this approach clears up some of the conceptual confusion in the literature, and therefore that Brattico and Pearce's proposal of using a pleasantness dimension to augment the valence dimension could instead be thought of as providing additional qualities of experience, rather than as adding a dimension that captures more variance within the same emotion space. Furthermore, our framework draws attention to the shallow hedonic tone implied by the terms pleasantness, preference, or enjoyment.

Conclusion

Our proposed framework can enable aesthetic experience to be defined in a parsimonious yet flexible way. It is parsimonious because at the nub of the aesthetic experience is internal locus, positive affect-valence. It is flexible because aesthetic experience for some will consist mainly or totally of deep affect-valences, while for others it will also include shallow ones (e.g., liking, pleasantness). The framework also allows for theory-building, so that instead of confusing emotion-like qualities with aesthetic experience, for example, researchers' questions might be arranged around how emotion-valence (distinct from other kinds of emotion-like experiences) impacts the affect-valence of the aesthetic experiences.

The framework aims to allow the detailed mapping and exploration of concepts loosely or directly concerned with 'emotional' responses and experiences in future research. As a result, it has the potential to open up new questions about aesthetic experience. We believe that some of the most important of these are:

1. Are there dichotomous or polychotomous demarcations between shallow versus deep affect-valence experiences, or do they merge into one another along a continuum? Some people differentiate between thrills and awe (the latter being a deeper level experience than the former), while for others no such differentiation is made, and at a coarser level the shallow-level affect-valence experience of liking can encapsulate some deeper levels of hedonic tone. We should point out that our conceptualization of hedonic tone in terms of depth is preferable to a term such as 'intensity' or 'magnitude', because those terms can then be reserved for the psychometric study of individual qualities, for example the level or magnitude of liking for something, as is frequently done in empirical aesthetics research. But the question of categories or continuum brings to our attention highly problematic terms such as 'pleasure', that have not only been used to measure self-report preference-like responses (e.g. Bradley & Lang, 2000; Do, Rupert, & Wolford, 2008), but are also associated with deep level 'aesthetic pleasure' (Reber, Schwarz, & Winkielman, 2004). As with Konečni's concept of aesthetic awe, a somewhat circular solution is adopted by adding the adjective 'aesthetic' for the deeper level experience, reflecting the approach to the ineffable as we move from pleasure to aesthetic pleasure, and awe to aesthetic awe. To test this question empirically one might seek to falsify the one-dimensional conceptualisation in terms of internal-locus affect-valence by finding examples of awe and thrills in art that are disliked. If the two can be consistently and systematically separated empirically, there is an argument for categorizing and separating different levels of affect-valence in the framework. With such evidence, hedonic tone could not consist of a simple continuum from shallow to deep.

2. Is there a limit to the kinds of objects, thoughts and events that can evoke deep-level, internal-locus affect-valence, or is this applicable in essence only to aesthetic experiences? This question could be easily addressed in a somewhat circular fashion by pointing out that any thing or situation that is not mundane can evoke deep level internal locus affect-valence, such as spectacular spaces and events in nature; revolutionary creation, invention or discovery; or catastrophic disasters (Mayer, 2008): Each of these phenomena provides examples of 'non-artistic'-generated deep, internal locus affect-valence (Konečni, 2005). But perhaps they can then all be integrated into the concept of 'aesthetic' rather than aesthetic versus other (nature, discovery etc.). Hence, we have two circularities: A. Deep affect-valence = aesthetic experience and, B. Deep affect-valence occurs in response to anything that is not mundane. Conversely, perhaps something only becomes an 'artistic' object if it can give rise to these kind of deep, internal-locus affect-valence responses.

3. Is it possible to have an aesthetic experience without affect-valence? That is, can one judge an object as beautiful, judge the experience to be aesthetic, but have no accompanying internal locus affect-valence? Current evidence suggests that internal locus affect-valence is essential for such experience (Grewe, Kopiez, & Altenmüller, 2009; Rickard, 2004; Salimpoor, Benovoy, Longo, Cooperstock, & Zatorre, 2009; Schubert, 2007a, 2010; Vuoskoski, Thompson, McIlwain, & Eerola, 2012), but we have not cited literature that explicitly tests this assertion. And so the affect-space model provides a new focus for future research programs seeking to investigate aesthetic experience.

The framework crystallises these three problems, and for the first two highlights the need to tease out the limitations, or accept the potential, arbitrary equivalences (e.g., aesthetic=non-mundane-high level affect-valence) when formulating research questions and providing analyses of aesthetic (and other) experiences. Our proposal is that external-locus judgements provide the context which shifts deep hedonic tone, internal locus affect-valence from non-aesthetic to aesthetic, and our affect-space framework presents a way in which an empirically driven approach could be used to address this question. If one is feeling awe without a particular object in mind, the deep hedonic tone might not be an aesthetic experience. But if it is as a result of contemplating a beautiful piece of music, it is. This is why the external locus, aesthetic judgment (Figure 1) also has a role to play in aesthetic experience.

In this paper we have proposed that future researchers of aesthetic experience should bear in mind (i) the distinction between locus (felt versus expressed), (ii) the emotion-valence and affect-valence distinction, and (ii) deep versus shallow hedonically toned affect-valence. The distinction between affect-valence and emotion-valence makes an important contribution to the understanding of aesthetic experience because it brings into focus two different qualities of aesthetic experience based on recent work in philosophy – the emotional character of something, 'emotion-valence'; and the attraction to or evaluation of that emotion, 'affect-valence'. The separation of affect from emotion via the affect-valence emotion-valence conceptualization also takes us closer, we think, to Sloboda & Juslin's (2010) idea of 'irreducible qualia', in which emotions are whittled down to their necessary and sufficient essence. Separating out the affect-valence from emotions is conceptually complex (there are many affect/emotion-valence overlaps), but by considering them as different 'qualia', we believe much confusion between emotion and affect-valence responses/experiences can be reconsidered from a theoretical and empirical perspective.

Shallow affect-valence provides one index of the aesthetic experience, but we also argue that the essence of aesthetic experience may be better encapsulated by deep, internal-locus affect-valence terms such as awe, frisson and being moved. That is, shallow hedonic tone is a proxy for the deeper hedonic tone associated with aesthetic experience. But if empirical aesthetics researchers hope to gain further insight into aesthetic experience, our framework suggests, deep aesthetic experience needs to be somehow measured. We hope that this new framework will help to further advance the debate about the nature of aesthetic experience, and build toward a testable model for future empirical aesthetics research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research reported in this paper was supported by the Australian Research Council (FT120100053).

NOTES

-

Correspondence can be addressed to: Prof. Emery Schubert, Empirical Musicology Laboratory, School of the Arts and Media, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, E.Schubert@unsw.edu.au.

Return to Text -

It should be noted that our use of the analogy deep-shallow does not relate to the level of cognitive processing as expounded, for example, by Craik and Lockhart (1972).

Return to Text -

Please note that the clusters of words are sample words, not intended to be listed in any particular order.

Return to Text

REFERENCES

- Adorno, T. W. (1997). Aesthetic theory (R. Hullot-Kentor, Trans.). London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Armstrong, T., & Detweiler-Bedell, B. (2008). Beauty as an emotion: The exhilarating prospect of mastering a challenging world. Review of General Psychology, 12(4), 305. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012558

- Augustin, M. D., Wagemans, J., & Carbon, C.-C. (2012). All is beautiful? Generality vs. specificity of word usage in visual aesthetics. Acta Psychologica, 139(1), 187-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.10.004

- Beardsley, M. C. (1969). Aesthetic experience regained. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 28(1), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.2307/428903

- Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and psychobiology. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Berlyne, D. E. (1972). Ends and means of experimental aesthetics. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 26(4), 303-325. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0082439

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2000). Affective reactions to acoustic stimuli. Psychophysiology, 37(2), 204-215. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8986.3720204

- Brattico, E., Bogert, B., & Jacobsen, T. (2013). Toward a neural chronometry for the aesthetic experience of music. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(article 206). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00206

- Brattico, E., & Pearce, M. (2013). The neuroaesthetics of music. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(1), 48-61. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031624

- Budd, M. (2008). Aesthetic essays. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199556175.001.0001

- Bullot, N., & Reber, R. (2013). The artful mind meets art history: Toward a psycho-historical framework for the science of art appreciation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(02), 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12000489

- Burke, E. (1806/1757). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. Philadelphia: J. Watts.

- Calvo-Merino, B., Jola, C., Glaser, D. E., & Haggard, P. (2008). Towards a sensorimotor aesthetics of performing art. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 911-922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2007.11.003

- Cela-Conde, C. J., Agnati, L., Huston, J. P., Mora, F., & Nadal, M. (2011). The neural foundations of aesthetic appreciation. Progress in Neurobiology, 94(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.03.003

- Charland, L. (2005). The heat of emotion: Valence and the demarcation problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 12, 8(10), 82-102.

- Chatterjee, A. (2004). Prospects for a cognitive neuroscience of visual aesthetics. Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts, 4(2), 56-60.

- Chatterjee, A., & Vartanian, O. (2014). Neuroaesthetics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 370-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.003

- Cochrane, T. (2010). Music, emotions and the influence of the cognitive sciences. Philosophy Compass, 5(11), 978-988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2010.00337.x

- Cochrane, T. (2012). The emotional experience of the sublime. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 42(2), 125-148. https://doi.org/10.1353/cjp.2012.0003

- Cohen, A. J. (2010). Music as a source of emotion in film. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications. (pp. 879-908). Oxford: OUP.

- Colombetti, G. (2005). Appraising valence. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 12(8-10), 103-126.

- Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 11(6), 671-684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

- Crisp, R. (2006). Hedonism reconsidered. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 73(3), 619-645. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1933-1592.2006.tb00551.x

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Dickie, G. (1997). Introduction to aesthetics: An analytic approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Do, A. M., Rupert, A. V., & Wolford, G. (2008). Evaluations of pleasurable experiences: The peak-end rule. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(1), 96-98. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.15.1.96

- Evans, P., & Schubert, E. (2008). Relationships between expressed and felt emotions in music. Musicae Scientiae, 12(1), 75-99. https://doi.org/10.1177/102986490801200105

- Gabrielsson, A. (2002). Perceived emotion and felt emotion: Same or different? Musicae Scientiae, 6(1; Special Issue), 123-148.

- Grewe, O., Kopiez, R., & Altenmüller, E. (2009). The chill parameter: goose bumps and shivers as promising measures in emotion research. Music Perception, 27(1), 61-74. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2009.27.1.61

- Hanich, J., Wagner, V., Shah, M., Jacobsen, T., & Menninghaus, W. (2014). Why we like to watch sad films. The pleasure of being moved in aesthetic experiences. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035690

- Hanslick, E. (1854/1957). The beautiful in music (G. Cohen, Trans. 7 ed.). New York: Liberal Arts Press.

- Hargreaves, D. J. (1986). The developmental psychology of music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511521225

- Hargreaves, D. J. (2012). Musical imagination: Perception and production, beauty and creativity. Psychology of Music, 40(5), 539-557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735612444893

- Hekkert, P., Snelders, D., & Wieringen, P. C. (2003). 'Most advanced, yet acceptable': typicality and novelty as joint predictors of aesthetic preference in industrial design. British Journal of Psychology, 94(1), 111-124. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603762842147

- Ingarden, R. (1961). Aesthetic experience and aesthetic object. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 21(3), 289-313. https://doi.org/10.2307/2105148

- Jacobs, R., Renken, R., & Cornelissen, F. W. (2012). Neural correlates of visual aesthetics–beauty as the coalescence of stimulus and internal state. PloS One, 7(2), e31248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031248

- Jacobsen, T. (2006). Bridging the arts and sciences: A framework for the psychology of aesthetics. Leonardo, 39(2), 155-162. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2006.39.2.155

- Juslin, P. N. (2013). From everyday emotions to aesthetic emotions: Towards a unified theory of musical emotions. Physics of Life Reviews, 10(3), 235–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2013.05.008

- Juslin, P. N., Harmat, L., & Eerola, T. (2014). What makes music emotionally significant? Exploring the underlying mechanisms. Psychology of Music, 42(4), 599–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735613484548

- Juslin, P. N., Liljeström, S., Västfjäll, D., & Lundqvist, L.-O. (2010). How does music evoke emotions? Exploring the underlying mechanisms. In P. N. Juslin & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion: theory, research, and applications (pp. 605-642). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Juslin, P. N., & Sloboda, J. A. (2010). Introduction, aims, organization, and terminology. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Music and Emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 3-12). Oxford: OUP.

- Juslin, P. N., & Västfjäll, D. (2008). Emotional responses to music: The need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31(5), 559-575.

- Kant, I. (1952/1790). The critique of judgement (J. C. Meredith, Trans.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 17(2), 297-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

- Kivy, P. (1989). Sound sentiment: An essay on the musical emotions, including the complete text of The Corded shell. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Konečni, V. J. (2005). The aesthetic trinity: Awe, being moved, thrills. Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts, 5(2), 27-44.

- Konečni, V. J. (2012). Empirical Psycho-Aesthetics and Her Sisters: Substantive and Methodological Issues—Part I. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 46(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.46.4.0001

- Kuehnast, M., Wagner, V., Wassiliwizky, E., Jacobsen, T., & Menninghaus, W. (2014). Being moved: linguistic representation and conceptual structure. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01242

- Langer, S. K. (1957). Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art. (3 ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Leder, H., Belke, B., Oeberst, A., & Augustin, D. (2004). A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. British Journal of Psychology, 95(4), 489-508. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007126042369811

- Leder, H., & Nadal, M. (2014). Ten years of a model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments: The aesthetic episode–Developments and challenges in empirical aesthetics. British Journal of Psychology, 105(4), 443-464. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12084

- Levinson, J. (1992). Pleasure and the value of works of art. British Journal Of Aesthetics, 32(4), 295-306. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaesthetics/32.4.295

- Locher, P., Overbeeke, K., & Wensveen, S. (2010). Aesthetic interaction: A framework. Design Issues, 26(2), 70-79. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00017

- Martin, F. D. (1956). On the Supposed Incompatibility of Expressionism and Formalism. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 15(1), 94-99. https://doi.org/10.2307/427497

- Maslow, A. H. (1948). "Higher" and "lower" needs. The journal of psychology, 25(2), 433-436. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1948.9917386

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

- Mayer, A. (2008). Aesthetics of Catastrophe. Public Culture, 20(2), 177-191. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2007-022

- Naukkarinen, O. (2010). Why beauty still cannot be measured. Contemporary Aesthetics, 8. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7523862.0008.007

- Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The Measurement of Meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Perlovsky, L. (2002). Physical Theory of Information Processing in the Mind: concepts and emotions. SEED On Line Journal, 2(2), 36-54.

- Perlovsky, L. (2014a). Aesthetic emotions, what are their cognitive functions? Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00098

- Perlovsky, L. (2014b). Mystery in experimental psychology, how to measure aesthetic emotions? Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01006

- Plutchik, R. (1962). The emotions: Facts, theories and a new model. New York: Random House.

- Pouivet, R. (2000). On the cognitive functioning of aesthetic emotions. Leonardo, 33(1), 49-53. https://doi.org/10.1162/002409400552234

- Reber, R., Schwarz, N., & Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver's processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 364. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3

- Rickard, N. S. (2004). Intense emotional responses to music: a test of the physiological arousal hypothesis. Psychology of Music, 32(4), 371-388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735604046096

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 1161-1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

- Russell, J. A. (1989). Measures of emotion. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory research and experience. (Vol. 4, pp. 81-111). New York Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-558704-4.50010-4

- Salimpoor, V. N., Benovoy, M., Longo, G., Cooperstock, J. R., & Zatorre, R. J. (2009). The rewarding aspects of music listening are related to degree of emotional arousal. PloS one, 4(10), 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007487

- Scherer, K. R. (1984). On the nature and function of emotion: A component process approach. In R. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds.), Approaches to emotion (pp. 293-317). London: Erlbaum.

- Scherer, K. R. (2004). Which emotions can be induced by music? What are the underlying mechanisms? And how can we measure them? Journal of New Music Research, 33(3), 239-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0929821042000317822

- Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information, 44(4), 695-729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018405058216

- Scherer, K. R., & Zentner, M. R. (2001). Emotional effects of music: Production rules. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Music and emotion: Theory and research. (pp. 361-392). Oxford: OUP.

- Schimmack, U. (1999). Structural models of mood: Review, overview, and outlook. Psychologische Rundschau, 50(2), 90-97. https://doi.org/10.1026//0033-3042.50.2.90

- Schimmack, U., & Grob, A. (2000). Dimensional models of core affect: A quantitative comparison by means of structural equation modeling. European Journal Of Personality, 14(4), 325-345. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0984(200007/08)14:4%3C325::AID-PER380%3E3.0.CO;2-I

- Schimmack, U., & Rainer, R. (2002). Experiencing activation: Energetic arousal and tense arousal are not mixtures of valence and activation. Emotion, 2(4), 412-417. https://doi.org/10.1037//1528-3542.2.4.412

- Schlosberg, H. (1952). The description of facial expressions in terms of two dimensions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44, 229-237. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055778

- Schlosberg, H. (1954). Three dimensions of emotion. Psychological Review, 61, 81-88. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054570

- Schubert, E. (1999). Measuring emotion continuously: Validity and reliability of the two-dimensional emotion-space. Australian Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 154-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539908255353

- Schubert, E. (2007a). The influence of emotion, locus of emotion and familiarity upon preference in music. Psychology of Music, 35(3), 499-515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607072657

- Schubert, E. (2007b). Locus of emotion: The effect of task order and age on emotion perceived and emotion felt in response to music. Journal of Music Therapy., 44(4), 344-368. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/44.4.344

- Schubert, E. (2010). Affective, evaluative and collative responses to hated and loved music. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(1), 36-46. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016316

- Schubert, E. (2012). Using Affect Valence and Emotion Valence to Understand Musical Experience and Response: The case of hated music. In W. L. Sims (Ed.), Proceedings of the 30th ISME World Conference on Music Education Music Pædeia: From Ancient Greek Philosophers Toward Global Music Communities (pp. 317-324). Nedlands, Western Australia: International Society for Music Education

- Schubert, E. (2013a). Emotion felt by the listener and expressed by the music: literature review and theoretical perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 837. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00837

- Schubert, E. (2013b). Loved music can make a listener feel negative emotions. Musicae Scientiae, 17(1), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864912461321

- Schubert, E. (2016). Enjoying sad music: Paradox or parallel processes? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10(article 312). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00312

- Scruton, R. (1983). The Aesthetic Understanding: Essays in the Philosophy of Art and Culture. London: London: Methuen.

- Shusterman, R. (1997). The end of aesthetic experience. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 55(1), 29-41. https://doi.org/10.2307/431602

- Sloboda, J. A., & Juslin, P. N. (2010). At the interface between the inner and outer world: Psychological perspectives. In J. A. Sloboda & P. N. Juslin (Eds.), Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 73-97). Oxford, UK: OUP.

- Thakral, P. P., Moo, L. R., & Slotnick, S. D. (2012). A neural mechanism for aesthetic experience. Neuroreport, 23(5), 310-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0b013e328351759f

- Tinio, P. P. (2013). From artistic creation to aesthetic reception: The mirror model of art. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(3), 265-275. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030872

- Trost, W., Ethofer, T., Zentner, M., & Vuilleumier, P. (2012). Mapping aesthetic musical emotions in the brain. Cerebral Cortex, 22(12), 2769-2783. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhr353

- Vartanian, O., & Skov, M. (2014). Neural correlates of viewing paintings: Evidence from a quantitative meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Brain and cognition, 87, 52-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.03.004

- Vuoskoski, J. K., Thompson, W. F., McIlwain, D., & Eerola, T. (2012). Who enjoys listening to sad music and why? Music Perception, 29(3), 311-317. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2012.29.3.311

- Wundt, W. (1897). Outlines of Psychology (C. H. Judd, Trans.). Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann. https://doi.org/10.1037/12908-000

- Zatorre, R. J., & Salimpoor, V. N. (2013). From perception to pleasure: music and its neural substrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(Supplement 2), 10430-10437. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1301228110

- Zentner, M. R., Grandjean, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2008). Emotions evoked by the sound of music: Characterization, classification, and measurement. Emotion, 8(4), 494-521. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.4.494