IN his rich and sophisticated paper, "Musical Empathy, Emotional Co-Constitution, and the 'Musical Other,'" Deniz Peters (2015) offers an original and important contribution to our understanding of musical experience. The chief features of Peters' account are: (1) it aims to be non-reductive; (2) it takes seriously the contributions of bodily experience; and (3) it offers a novel theory of what Peters calls "musical empathy." These features are closely interrelated. In what follows, I shall discuss what I take to be the significance of Peters' line of thinking and offer suggestions about some research implications of the view.

The Structural Object Model

In order to understand the significance of Peters' contribution let me first set out the parameters of a view against which Peters' account stands, a view I shall call the "Structural Object Model." The Structural Object Model underwrites much thinking about music across academic disciplinary boundaries and in the minds of composers, performers, critics, and members of the public at large.

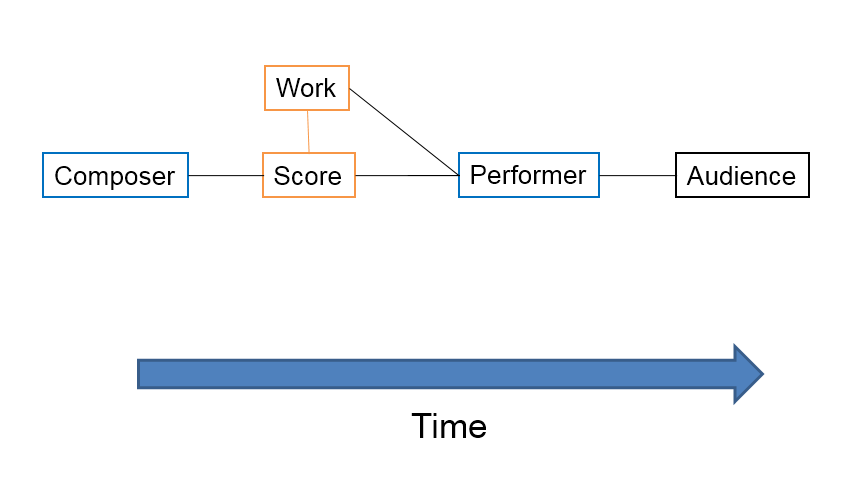

On the Structural Object Model, music is seen as a particular kind of human activity involving agents engaged in the production and appreciation of certain sorts of objects, viz., musical works of art. Typically, composers create the works whose repeatability and transmission are enabled by the development of musical notation and scores such that we can say, for example, "Last night I heard a performance of Mahler's 2nd Symphony." Scores provide the means by which performers can make musical works of art available to audiences. On the Structural Object view the production of music can be seen as a two-stage performing art involving (1) composition and (2) performance of musical works designed for the attention of listeners. Musical experience for the listener or audience (which can include composers and performers as they engage in the act of listening) involves listening to the object produced by the composer and performer enabled by the work (see Figure 1).

If musical experience for the listener involves listening to a certain sort of object, what sort of object are we talking about? Following a line of thought about the modern system of the fine arts developed in the 18th century (see Kristeller, 1965), the Structural Object Model proposes that the relevant object of attention of the listener be considered aesthetically, as formal musical patternings and associated mimetic, expressive, and representational properties of works that can be appreciated for their own sake in a "disinterested" manner, largely independent of non-aesthetic uses or values the object might have. Musical works in this sense are autonomous objects, created by composers and constituted by their intrinsic musical and aesthetic properties. The musical work of art, ontologically speaking, is the musical idea, the structure, entity, or type whose tokens are datable, locatable patterns of sounds constituted by the composer (Hanslick, 1954/1986; Dodd, 2007, 2010). However rich and dense our descriptions of music might be, it is the sounds that are the primary and originative core of the work. Performances may be heard and appreciated in terms of their fidelity to the sounding meaning(s) suggested or proscribed by the score.

Moreover, since music is a temporal art with its objects presented as events occurring in real time, the experience of the musical object is a matter of contemplating intrinsic musical qualities dynamically in their developing relationships. We "follow" music precisely because the musical work consists, as Hanslick famously put it, in "tonally moving forms." Hanslick was particularly restrictive in his description of musical forms, limiting relevant properties strictly to "purely" musical qualities and their relations to the exclusion of emotive/expressive qualities. Most proponents of the Structural Object Model, however, have a less restrictive view, advancing an "enhanced" version of formalism, embracing those expressive and representational properties of musical works that can be appreciated aesthetically (Alperson, 1991). Whether one speaks of "purely" musical properties or the representative and expressive properties that may emerge from or be attendant upon them, the musical forms of aesthetically rewarding musical works of art are typically described as having a patternability, logic, or rational coherence rooted in musical "laws" such as the law of harmonic progression. Accordingly, one may speak of musical "thinking" and of the musical "understanding" by means of which we follow structural development in the musical object.

For present purposes, then, we may say that the Structural Object Model features the following salient characteristics: (1) the assumption of the modern Western paradigm of composed music in which (2) the musical work, (3) considered as a created entity, (4) takes center stage in terms of both musical production and appreciation, where (5) the properties considered to be relevant to musical activities are taken to be musical or musically-derived aesthetic properties and relations, to the exclusion of "extra-musical" (i.e. non-musical or non-aesthetic) considerations, and (6) which are thought to be apprehended in an "intellectualistic" or "rationalistic" manner by means of the contemplation or inspection of musical ideas (7) in suitably cultivated listeners. I submit that this picture is a working model in the minds of many musicians, teachers, critics, and scholars.

Peters' View

We can see straightaway the contributions of Deniz Peters' account of musical experience. Like proponents of the Structural Object Model, Peters is concerned mainly with the Western paradigm of composed musical works performed before an audience. Further, like advocates of the Structural Object Model, Peters holds that whatever meaning might be properly ascribed to musical works in musical experience derives from "the music's detailed qualities, in the sense that it is specifically related to how qualities and their complex interrelations were composed and are being performed," to the "heard musical character" of the music, "in the music and its sounding realization" (2015, p. 5) . In the particular case of musical expressivity, what is to be accounted for is the expressivity of "the music," i.e. the music's "own" expressivity.

However, whereas the Structural Object Model considers the work as a created entity—essentially a product of the composer even when presented through the interpretations of performers and which is functionally independent and typically temporally separated from the musical experience of listeners—Peters argues that the work is co-constituted, brought into being with the active productive and constructive activity of the listener. In this regard, Peters' account can be understood as a move against a certain kind of reductionism with which the Structural Object Model might be charged, namely regarding the musical work as a completed thing, such as a physical or natural object or perhaps a natural kind such as H20. Peters' antireductionism here amounts to a critique of the Structural Object Model's tendency toward entity realism.

Peters' account is also non-reductive in the sense that his account of the mode of musical apprehension is not limited to the perception of sounds considered as auditory phenomena narrowly construed. True, Peters is, as we have seen, concerned with musical experience of the "heard detail" of music, but, on Peters' account, the "heard" aspects of music are inescapably bodily. This is not to say that Peters replaces the narrow auditory view of musical perception with an alternatively reductionist neurophysiological view based on the functioning of mirror neurons. As Peters rightly points out, the activity of mirror neurons is at a far remove from such highly specialized actions as piano, koto, or cello playing. Peters antireductionism rather here amounts to a twofold claim about musical perception. First, on Peters' view, musical perception, like other forms of auditory perception, is cross-modal, involving other modes of perception than hearing alone. Second, the cross-modality of musical perception permits and fosters a bodily hermeneutic, an active bodily component to musical apprehension rooted in our "corpophonic" embodied knowledge of sonic—tactile—kinaesthetic correspondences in everyday experiences. This form of antireductionism which posits the active contribution of our knowledge of the felt aspects of everyday life to specifically musical experience stands against the tendency of the Structural Object Model to over-intellectualize musical experience. 3

This view of musical experience leads Peters to make three further claims about the musical experience of musical expressivity in particular of performed music. First, Peters holds that the felt level of musical experience has phenomenological priority. Whatever other kinds of expressivity we might find in a musical performance, that expressivity is derivative of the experience of the bodily felt aspects of the musical sounds themselves. Second, since the expressivity of a musical passage or piece is co-constituted by the listener, reflecting his or her own knowledge and history of the felt world in a lived body as well as the performer's expressive interpretation, the emergent agency of the expressivity is initially indeterminate, allowing for a certain flexibility in our attributing agency to the expressivity: we may feel that the anger of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring originates in us, or that it is something to which we are subjected, or that it is something removed from us, etc. Third, the mode of musical expressivity is what Goldie (2000) calls "adverbial" but, on Peters' view, in a specifically bodily way: we appreciate, by means of "bodily inklings," the felt quality of sonic shapes against the context of the imaginative horizon of our bodily knowledge of the colorings of our own bodily actions. There is then a connection between musical expressivity and a persona, but the connection is with a specifically musical persona that is our attribution, influenced by a range of soundings, listenings, imaginings, and encounters, allowing us to drift from one attribution to another in the course of a single musical episode. This experience of musical empathy is compatible with, and may even help to sustain, instances of social empathy, as when we join together with others in shared musical experiences in particular social, historical, and cultural contexts, which can in turn feed back on our experience of the work or the performance. Musical empathy can have an important role to play in the social dynamics of ensemble playing, for example. 4 There is, then, a dialectic relationship between musical and social empathy.

Implications, Elaborations, Extensions

One of the measures of a rich and constructive theory is its generative power, i.e. its ability to suggest interesting and insightful implications that challenge prevailing ways of thinking, offer new ways of talking about things, and suggest new areas of theoretical analysis and empirical research. Peters' account of musical perception as a doubly active affair in which bodily knowledge extends auditory perception cross modally and orients a bodily hermeneutic provides important insights about musical experience that will resonate deeply with many listeners. In this section, I should like to address some of the implications and challenges of Peters' theory. I cannot of course hope to cover all the issues that Peters' essay raises.

Let us consider first the matter of the extension of such a theory, which I mean in the technical sense of the range of musical experiences the theory might be thought to cover. There are times when Peters' theory seems to be advanced as a general account of "the" musical experience of listeners. At the same time Peters acknowledges something of the variability of listeners' responses, allowing that "the hermeneutic and imaginative horizon of each person involved makes a difference and contributes to the listening experience" (2015, pp. 9-10) .

Let us press this matter of the variability of listener responses by considering first the extent of listener variability. I think that Peters is right to point out that, as listeners, we often bring our corpophonic knowledge to bear on musical experience and, to that extent, we co-constitute the experience. At the same time, listeners differ significantly with respect to their aptitude and the range of the bodily musical experiences they bring to the music they hear. As a woodwind player with many years of playing experience, I have a fairly well developed sense of what it feels like to change timbres from soft, more rounded to edgier tones on woodwind instruments, what it feels like to articulate a series of notes by means of different tonguing techniques, and I have a knowledge of the pressures and feels of the embouchure, lips, jaw, throat, and tongue in producing certain kinds of sounds. I often bring this knowledge with me to my listening experience. Thanks to a few lessons I have taken, I also have an analogous, if less well developed, knowledge of what it is like to produce and to feel some of the characteristic sounds of certain styles of Tuvan throat singing. I have only the most rudimentary knowledge of what it is like to produce sounds on the trumpet, having tried to play the instrument once one afternoon. Nevertheless, I sometimes bring even that limited felt knowledge to bear on the music I hear, as for example, when I hear and know why a note has popped out of Rolf Ericson's trumpet a little late in bar 31 of his solo on "The Meaning of the Blues" on Stan Kenton's Standards in Silhouette recording. There are people who almost certainly have less corpophonic musical knowledge than I have. Many people have no first-hand knowledge of musical sounds by way of performing them on musical instruments. Some people are congenitally and profoundly deaf and have never heard music, except perhaps as an assemblage of pulses. Some people can hear but they are tone deaf. Some people can discriminate tones but they are tune deaf—they cannot recognize a melody as a melody. And, as Peters point out, there are some bodily experiences and actions, such as the right hand bowing technique of a violin player or what is happening inside a wind-player's mouth that might go unnoticed even by many high-level professional players.

Additionally, quite apart from listeners' experience and abilities vis-à-vis the sort of corpophonic involvement Peters discusses so ably, listeners bring to musical understanding different preconceptions and orientations about what constitutes proper or preferred modes of musical attention. At a recent performance of Richard Strauss' Also Sprach Zarathustra by the Philadelphia Orchestra, I noticed myself listening to the performance in a way that seemed to me consistent with Peters' account. At the same performance, however, I noticed a person across the aisle, whom I shall call "the nodder," who was intent on marking the downbeat of major rhythmic stresses (and only major rhythmic stresses) with large, overt hand gestures—corpophonic to be sure but, I suspect, his attention seemed overly oriented toward the rhythmic side of things. The person on my left was studiously following the score on an iPad. Having Peters' essay in mind I asked her how she would characterize her experience of the piece while following the score. "More structural," she said. "I concentrate more on the developing organization and seem less involved with the bodily force of the music. At times my attention seems focused entirely on the abstract development I understand through the score." The person to my right seemed to be at a far remove from the music, glancing around the hall constantly during the performance. Was he tune or tone deaf? Was he musically sophisticated but somehow put off by the particular interpretation of Strauss' work on offer that night? Was he distracted by a more pressing concern? Obviously, I could not know. Indeed, my descriptions of all the listeners except my own are inferential. Still, it seems evident that there were definite musical styles of musical apprehension on display in the hall.

From these reflections I take the following general points about the extension of Peters' theory. First, there are cases where Peters' theory seems to apply and where the view yields important insights about the bodily nature of music as experienced. Second, in those cases where the theory seems applicable, there is likely to be a wide range of backgrounds listeners bring to bear in their co-constitution of the music, as the case of the nodder suggests. Third, there seem to be modes of attention where the bodily or felt aspect of the music is considerably, if not severely, attenuated. We would be less inclined to say of the score reader that the felt level of perception had the phenomenological priority in her experience of the music of even the nodder. This is due to the fact that, from a phenomenological point of view, inward hearing stops short of the power and determinateness of quality and duration which characterizes actual sensation (Langer, 1953, chapter 3).

But if there are different modes of musical apprehension, some of which do not fit easily under the orbit of Peters' account, the question arises: what sort of model is being proposed? What are we to make of those listening experiences that do not seem to be bodily in the way in which theory proposes? Put differently, if the theory is not intended to be widely descriptive, are we to assume it is a normative theory establishing or favoring a certain standard of correctness in musical attention? Peters does not intend the theory to be taken this way 2 but, precisely because the theory seems so well suited to certain modes of listening and less so others, the question of how we are to classify and evaluate various modes of musical apprehension comes to the fore.

The question of normativity is related to another set of important questions: what range of musical practices is the model intended to cover? We noted earlier that, like proponents of the Structural Object Model, Peters is concerned mainly with the Western paradigm of composed musical works performed before an audience and, like the proponents of that model, Peters' concern is, in the first instance, with the details of the music itself. It is not hard to see that Peters' model can be applied without much adjustment to certain musical practices not quite at the center of the practice of composed music. Consider the case of musical improvisation. It can be argued that in improvised music the idea of a work created first by a composer and then presented to a public that I have attributed to the Structural Object Model dissolves (Alperson, 1984). I take it as a virtue of Peters' model that its account of musical listening experience can be applied without remainder to improvised music, at least insofar as it makes sense to view improvised music as presenting the kinds of musical patternings amenable to musical experience that composed music provides. Similarly, it is not hard to see how, with suitable adjustments, the view might be applied to instances of recorded music. But what do we say of musical traditions where the aesthetic and "purely" musical detail figures less centrally in musical experience? Or, for that matter, of music in which expressivity (and hence musical empathy) is not as central a feature? Take the example of gong music used in many Asian mountain cultures to mark significant events in the animistic, agrarian, and ancestral aspects of traditional ethnic life. To be sure, there are interesting musical and aesthetic qualities to the music but the focus of attention in the practices is less on these aspects than on the mundane, ritual, and sacred meanings of the events at which the music is played. Of course, one might say, "Well that isn't 'real' music or music in 'our' sense," but such pronouncements are fraught in ways we unfortunately do not have the space to explore here.

Peters is himself clearly attuned to this question, saying at the outset that his theory is not directed toward cases where musical experience is "only accidentally related to the heard detail" (p. 2). What I mean to do here is to draw attention to the matter of identifying criteria according to which we regard particular aspects of music accidental, central, or even essential, a question which has important implications for both theoretical and empirical studies of music. It is part of the generative power of Peters' account that it sets before us such questions. For, as we have seen, one of the virtues of Peters' account is precisely the determined effort to offer a non-reductive account of music. I earlier identified two targets of Peters' non-reductionist campaign: the Structural Object Model's tendency toward entity realism and the model's over-intellectualization of musical experience. Can we push Peters' anti-reductionism further? Peters' concept of co-constitutionality, it seems to me, in particular provides the means to explore a more direct and robust consideration of deeply cultural issues.

Consider, as an example, the question of musical "sophistication." What is it to be musically sophisticated? There have been empirical studies of the topic. One study, the Ollen Musical Sophistication Index (Ollen, 2006) proposes a mathematical model for evaluating musical sophistication of musicians based on nine measurable indicators: college music coursework completed, age, age at commencement of musical activity, years of private lessons, years of regular practice, current time spent practicing, composition experience, concert attendance, and rank as music-maker. A second, the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index employs a range of psychometric variables grouped under five general categories (active engagement with music, perceptual abilities, musical training, singing abilities, and "emotions") to assess the musical sophistication of non-musicians (Müllensiefen et al., 2014). Surely, however, sophistication in musical experience goes beyond the kinds of abilities, backgrounds, and skills these variables are intended to capture. Say members of an audience enter into a post-concert discussion of whether a particular performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 2 was too pretty, perhaps because the conductor was too young to fully grasp the tendentiousness, the dissonance, the futility, and the despair of the music and of life. Or suppose that one listens to Charles Mingus' famous 1959 recording of his tune, "Fables of Faubus," hears the alternation of passages of angular, stiff dotted eighth and sixteenth rhythms with passages of straight-ahead no nonsense hard bop swing, and considers this as Mingus' bitterly ironic commentary on Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, who in 1957 sent the National Guard in to prevent the racial integration of Little Rock Central High School. I take these two cases to be instances of genuine musical sophistication. It may be that some of these considerations are consistent with experiencing musical features more narrowly construed. But the analysis of the "musical" features themselves do not tell the whole story. If this is indeed the case, then the co-constitution of music is a thoroughly cultural affair, something that must be reflected in theoretical and empirical researches alike.

NOTES

- Correspondence can be addressed to: Dr. Philip Alperson. E-mail: alperson@temple.edu.

Return to Text - Regarding his discussion of the example of a musical passage with a "pushing feel," Peters says, for example, "The point in my giving this broad example is, of course, not normative: it is not to prescribe, but to suggest some potential readings and experiences as an illustration of the way in which sounding materials, cross-modal perceptions, bodily hermeneutic, and ongoing emotional narrative interrelate and intertwine" (p. 9).

Return to Text - See also in this regard the work of Jenefer Robinson (1995, 2005).

Return to Text - See Alperson (2010) and Waddington (2013).

Return to Text

REFERENCES

- Alperson, P. (1984). On musical improvisation. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 43(1), 17-29.

- Alperson, P. (1991). What should one expect from a philosophy of music education? Journal of Aesthetic Education, 25(3), 215-242.

- Alperson, P. (2010). A topography of improvisation. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68(3), 273-80.

- Dodd, J. (2007). Works of music: An essay in ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dodd, J. (2010). Confessions of an unrepentant timbral sonicist. British Journal of Aesthetics 50(1), 33-52.

- Goldie, P. (2000) The emotions: A philosophical exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hanslick, E. (1854/1986). Vom Musikalisch-Schönen: Ein Beitrag zur Revision der östhetik der Tonkunst. (G. Payzant Trans.). On the musically beautiful: A contribution towards the revision of the aesthetics of music. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Kristeller, P. O. (1965). The modern system of the arts. In Renaissance thought II: Papers on humanism and the arts (pp. 163-227). New York: Harper & Row.

- Langer, S. K. (1953). Feeling and form. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons.

- Müllensiefen, D., Gingras, B., Musil, J., & Stewart, L. (2014). The musicality of non-musicians: An index for assessing musical sophistication in the general population. PLoS ONE 9(2), e89642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089642

- Ollen, J. (2006). A criterion-related validity test of selected indicators of musical sophistication using expert ratings. (Electronic Thesis or Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

- Peters, D. (2015). Musical empathy, emotional co-constitution, and the "musical other". Empirical Musicology Review, 10(1), 2-15 .

- Robinson, J. (1995). Startle. The Journal of Philosophy, 92(2), 53-74

- Robinson, J. (2005). Deeper than reason: Emotion and its role in literature, music, and art. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Waddington, C. E. (2013). Co-performer empathy and peak performance in expert ensemble playing. In A. Williamon & W. Goebl (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Symposium on Performance Science 2013 (pp. 331-336). Brussels, Belgium: European Association of Conservatoires (AEC).